How are writing and travel vehicles for understanding? How can we expand the literary canon to include other voices, other cultures, other experiences of the world?

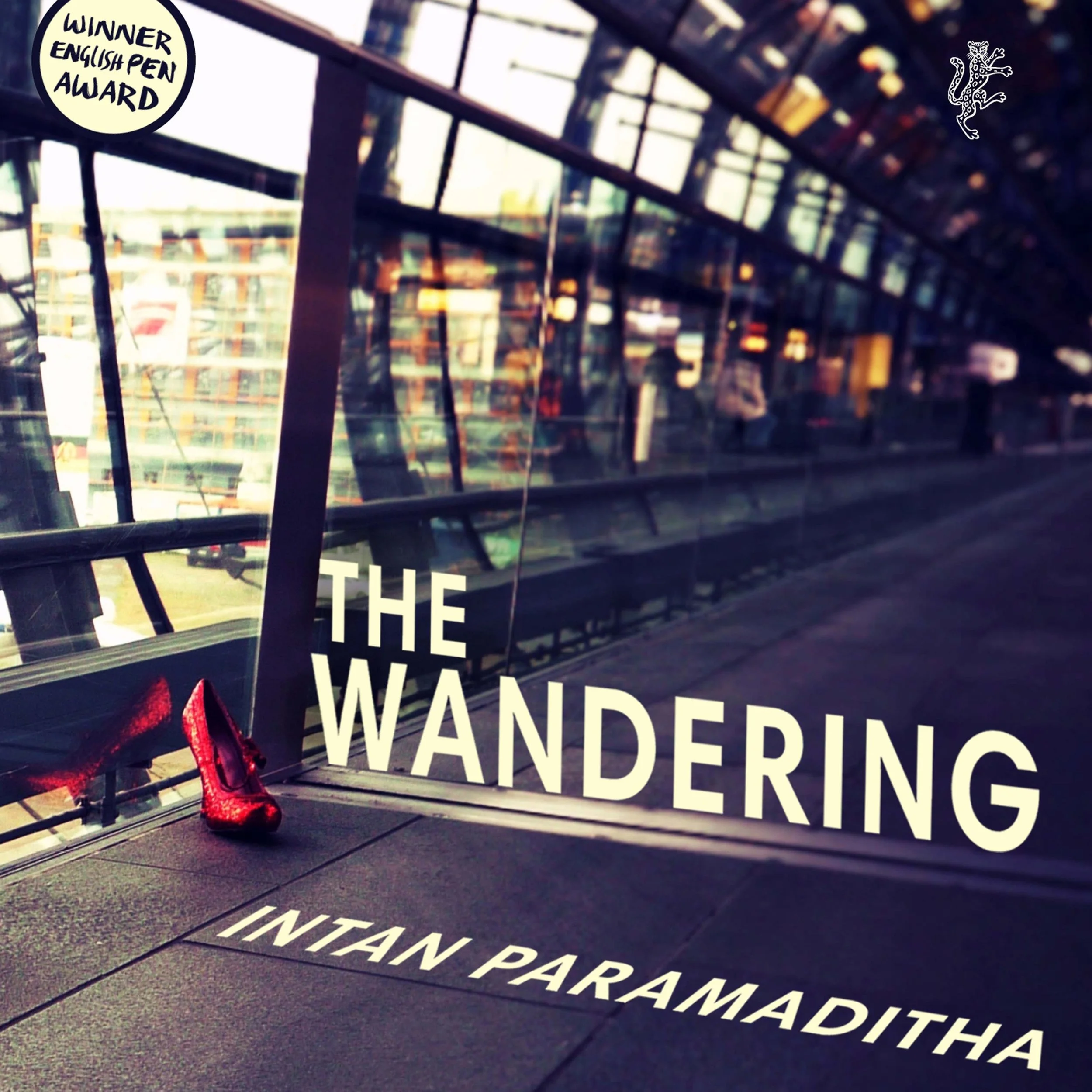

Intan Paramaditha is a writer and an academic. Her novel The Wandering (Harvill Secker/ Penguin Random House UK), translated from the Indonesian language by Stephen J. Epstein, was nominated for the Stella Prize in Australia and awarded the Tempo Best Literary Fiction in Indonesia, English PEN Translates Award, and PEN/ Heim Translation Fund Grant from PEN America. She is the author of the short story collection Apple and Knife, the editor of Deviant Disciples: Indonesian Women Poets, part of the Translating Feminisms series of Tilted Axis Press and the co-editor of The Routledge Companion to Asian Cinemas (forthcoming 2024). Her essay, “On the Complicated Questions Around Writing About Travel,” was selected for The Best American Travel Writing 2021. She holds a Ph.D. from New York University and teaches media and film studies at Macquarie University, Sydney.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS · ONE PLANET PODCAST

I've been enjoying The Wandering and your body of work. Your writing just flows. It's very accessible and clear. Right away in the first sentence you draw us in. It's a cinematic journey and at the same time an invitation to go inward and really examine what we can do with our lives—what will you do if you can take a ticket anywhere?

INTAN PARAMADITHA

The Wandering is a choose your own adventure novel, and the reader is situated in the shoes of this brown woman from the Global South. She's 27 and in a way, she is stuck with her life. She aspires to be middle class, but her job doesn't allow her to achieve this social mobility. In her condition, she makes a deal with a devil, a reference to the story of Faust and Mephistopheles, finally getting a pair of red shoes that will take her anywhere. But that means she will never be able to find home—that's the curse of the shoes. The title in Indonesian is Gentayanga, which is a word used to describe ghosts who exist in a liminal state. This is a metaphor for people who travel. I came up with the idea for this novel in 2009 when I was an Indonesian international student studying for my PHD in New York. When I went back to Jakarta, I felt like I was not at home, but New York wasn't my home either, so there's a feeling of being neither here nor there. I wanted to capture the sense of being everywhere, which is liberating, but also the sense of displacement.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

I'm wondering about the books you read growing up. As any young obsessive reader, I imagine you were always escaping into others' imaginations. You've written in Apple and Knife, and of course, in The Wandering, about your mother's influence upon your imagination.

PARAMADITHA

I grew up with folktales and fairytales from the Indonesian archipelago, from the Nusantara. And of course I grew up with the stories from the Grimm brothers and Hans Christian Andersen and actually I like them better than the Disney version because they're more bloody and gory. I guessed that also shaped my preferences for more dark and gothic stories as I grew up. I did English literature at the University of Indonesia. I wrote a BA thesis on Mary Shelley's Frankenstein. And my mother was a very imaginative person. She loved making her own stories, so I think I inherit that from her. But she never had the chance to explore her creative side—there were certain expectations for women at that time to get married. She was harsh. But I know why I considered her monstrous when she was younger. She was trying to reject society's expectations in her own way, but we didn't understand her. And so I became really interested in the so-called bad women or monstrous women, in a way that these women allow me to ask questions around the structures that create them. Her whole presence taught me to really appreciate the knowledge that was created by generations of women before me. Part of the work I do now is work with a feminist collective to actually question knowledge production, who is excluded from it, who is being marginalized because of it, and my mother played a great role in steering me in that direction.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

Yes, women can be labeled monsters just for claiming the rights that those who are privileged enough to have power and agency, expect. In your recent piece for Lit Hub, you write "I am not writing alone. I am writing with witches—those who have gone before, those who are brewing, and those who will rise."

PARAMADITHA

People around me, including writers, tend to talk about their influences, in ways that are taken for granted—usually they would mention names without really reflecting on why these authors. So it's really important to think about our influences in ways that are more political, more critical, and also more feminist. You need to be able to ask difficult questions, because sometimes the authors we admire are ideologically questionable, so it's really important to be critical and see our own personal canon as flexible. I'm always interested in witches. I was obsessed with gothic women writers—Mary Shelley, Margaret Atwood, Angela Carter—but because of the limitation of my knowledge, I didn't really include more writers of color. I didn't even know there was this Indonesian author Mariana Katopo that produced a feminist theology book, but the more I read, the more I expand my list of literary influences. Siti Rukiah wrote interesting stories that highlighted the condition of poor women, that were always intersectional, but her writing was banned in 1965 when the Suharto regime took over, so we never heard of her in our class. Sometime in 2000s, some leftist authors continued writing after they were detained for several years, but only the male authors; the women writers were really traumatized and concerned with the safety of their children, so when Rukiah got out of prison in the 70s, she decided not to write again. Just the difference between male and female writers, I think is interesting.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

And through the anthologies that you've edited, people can really discover some of these authors and we should really be able to open our minds beyond the traditional canon. And also, a central theme of your work is the right to travel, to reinvent ourselves, to explore in between states. At the same time, we're facing a very real ecological climate crisis, made worse by access to cheap travel.

PARAMADITHA

Some travel writers have shared a sense of responsibility in creating narratives around travel in relation to the climate crisis. But at the same time, I think we also need to first, raise critical awareness around the media productions that glamorize travel. What I learned from the feminist framework in climate justice is that climate change affects societies in uneven ways. So we also need to raise questions around the wealthy countries that take advantage of cheap labor or relocate production and emission in the Global South, and then they blame people in the Global South for being the contributors of the climate crisis. We really need to ask questions around the structures of people in power rather than focusing on individual responsibility. Whenever I encounter beauty, it's immediately disrupted. For instance, whenever I go to Bali, going to the beach and looking at the sunset, I'm reminded of the structures of global inequalities that make tourism possible. It's the same here in Sydney where I'm reminded this is a settler colonial country. But maybe it's important to appreciate the beauty of nature around you, but then be constantly disrupted by all these thoughts and questions.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

What are your reflections on AI and how it’s changing how we communicate with ourselves, with our imaginations and what lies ahead in terms of the digital divide?

PARAMADITHA

I've been playing with AI just to see what it can do. People who are not privileged with the skills of conceptualizing, the skills of abstract thinking, they will be replaced. And I'm just thinking about people from the Global South at this moment. People from the Global South have been working as supporters. They do a lot of support for the creative work of entrepreneurs in the Global North. They do social media. They create content and things like that. The people who would provide the support live in, let's say, the Philippines. So, what I'm worried about is how AI technology could take the jobs of people who are not really trained to sort of do conceptual thinking.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

Australia, where you now live, has, they say, among the most biodiversity of any country in the world, especially in terms of unique plants and animals. And yet, there is the flip side where you've had the Black Summer and these catastrophic events so that we have to work hard to preserve a more pristine nature. We really have to hold on to that and do all we can to preserve it. And as you think about the future, the writers who have influenced your imagination, and the importance of the arts, what would you like young people to know, preserve, and remember?

PARAMADITHA

It's important to imagine, to keep imagining, a world that is free from colonialism, from oppression, from exploitation, also expropriation of nature. And unfortunately this world is not sustainable—we are not living in that kind of world today. But if we want to see the world for our next generation for the future, we need to pass the torch and ask them to imagine, and then perhaps that way the struggle will continue.

This interview was conducted by Mia Funk with the participation of collaborating universities and students. Associate Interviews Producers on this episode were Katie Foster and Nadia Lam. Associate Text Editor was Nadia Lam. The Creative Process is produced by Mia Funk. Additional production support by Sophie Garnier.

Mia Funk is an artist, interviewer and founder of The Creative Process & One Planet Podcast (Conversations about Climate Change & Environmental Solutions).

Listen on Apple, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts.