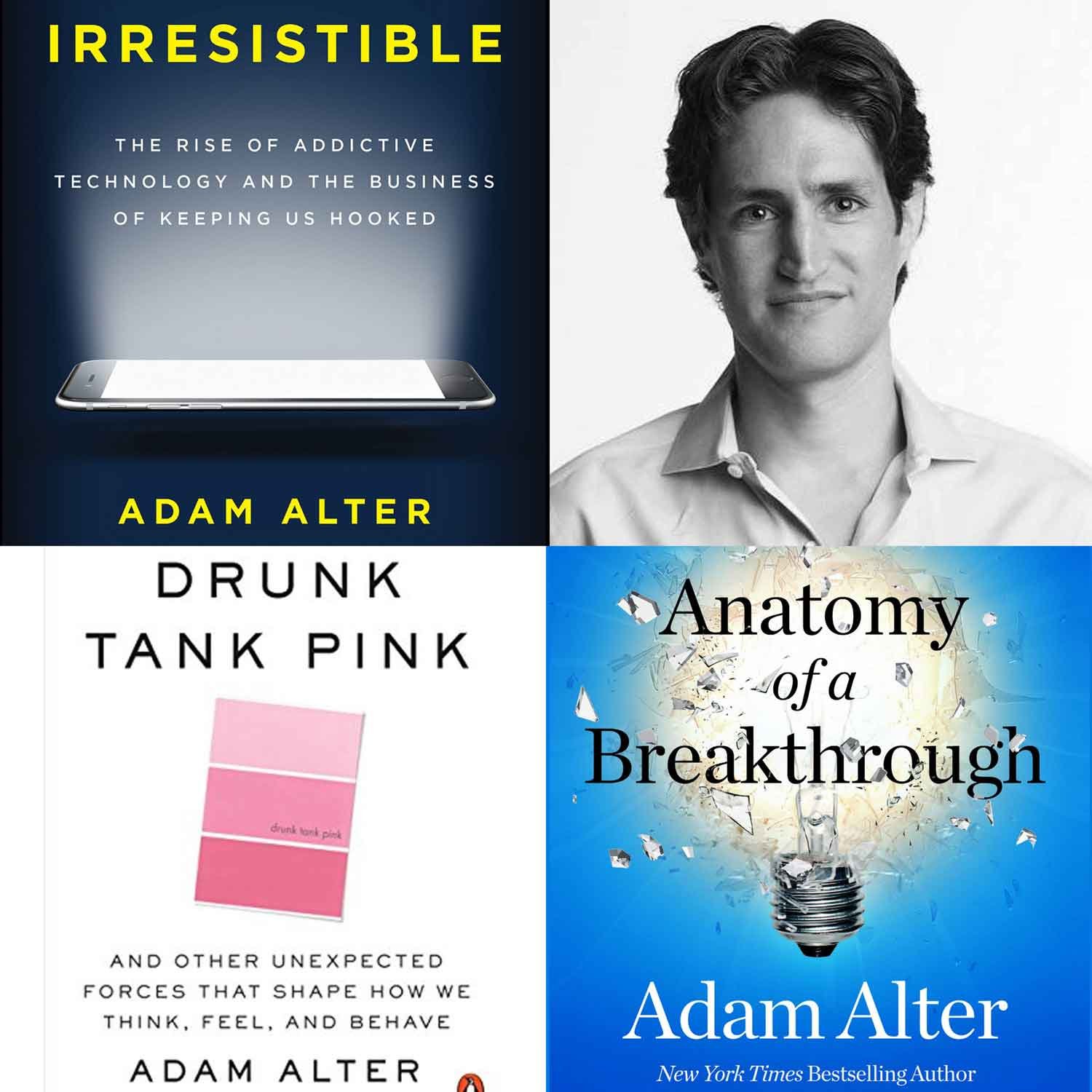

Adam Alter is a Professor of Marketing at NYU’s Stern School of Business and the Robert Stansky Teaching Excellence Faculty Fellow. Adam is the New York Times bestselling author of Irresistible: The Rise of Addictive Technology and the Business of Keeping Us Hooked, and Drunk Tank Pink, which investigates how hidden forces in the world around us shape our thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. He has written for the New York Times, New Yorker, The Atlantic, Washington Post, and a host of TV, radio, and publications. His next book Anatomy of a Breakthrough will be published in 2023.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

It would be nice to have monitors for technology, in the same way that we the Food and Drug Administration.

ADAM ALTER

I think having a “Food and Drug administration” for technology would be great. And one of the other ones that people bring up is this idea of the Hippocratic Oath, which suggests that if you're in the medical field, you're supposed to above all else, do no harm. That's your kind of guiding light, and it's a really useful, basic philosophical idea to use as your guide when you make decisions because it forces you to do this kind of pros and cons analysis with everything you're doing.

There is no Hippocratic Oath for tech, but it's a great idea, right? If Facebook says, “We're going to introduce the like button, what's the worst that can happen?” Turns out some pretty bad stuff can happen. But if you don't ask that question, you just don't turn your mind to those questions - or maybe you aren't forced to, maybe you know that they're there, but you just don't really look at the sun because the potential negatives are kind of overwhelming. So I agree, some oversight would be great. And that's why a lot of people think government legislation is critical with respect to technology because we can't just rely on consumers to empower themselves when everything is being done to undermine that power, and the government might need to get involved in some form.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

With all our distractions, it’s just very hard for us now to be alone with ourselves or be alone the people who matter to us most, but that's where the real imagination, the real transformation often takes place.

ALTER

So there are analog solutions to the digital problem. I think the single biggest solution, for most people, at least in terms of low-hanging fruit, the most obvious place to begin is to just say, I'm going to carve out time every day, create habits where I will not be near my devices at certain times of the day. It might be dinner time, maybe no matter where I am, whom I'm with, or what I'm doing, I will not during dinnertime use a device. Or it might be the first hour of the day. A lot of people do that, spend the first hour of the day tech-free. Have a cup of coffee, if that's what you like to do, read a physical newspaper, or just read a book - whatever you want to do. Or be with your kids or loved ones, depends what your situation is. And then the same before bed. So between 60 and 90 minutes before bed, don't use a phone. And even those small changes, no phone at dinner time, no phone first hour of the day, no phone an hour before bed. That will change your life.

It gives you back about two and a half hours of your day, which people when they start doing it, say, I can't believe I've lost that much time. So I think that there are many things we can do. We just have to make the decision to do them.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

You mentioned in your book how most addicts don't actually like the thing they're addicted to. It's just like the chemical rush in your brain that comes.

ALTER

So there are different parts of the brain responsible for liking and wanting. So wanting is unbelievably robust in the brain. In other words, the neural connections are very robust, and wanting is what drives most addictive behavior. It's when you really want something, like you want a cigarette, you want alcohol, a drug, whatever it is, that's your poison. And actually, screens for some people as well. The liking part. When you say to people, what does it mean to be addicted to something? A lot of people say it's, “You really like it so much that you just keep going back to it.”

It's actually not about liking. What actually happens is that, in the beginning, liking and wanting go together. So let's pick something like a cigarette. If you start smoking in the beginning, you like the experience of smoking, and you also really want the nicotine. You want the cigarette. They go hand in hand, but eventually what happens is the liking is much more fragile, and it decays. And what's left is the wanting. And often in the absence of liking, it's kind of like a bad relationship. Like if you're in a bad romantic relationship, it starts out being about wanting and liking, but then the liking goes away, and you just kind of want to be with a person, even though you know it's undermining your welfare. That's effectively addiction. The real skill today is figuring out how to create space between you and your tech devices.

And so you, maybe you do have to free solo up a rock face. That's your only real option if that's the kind of pursuit that you're interested in, but I think for the rest of us, those of us who aren't doing that, there has to be a kind of down-to-earth version of that, which is to say, ask yourself how much of the day you can't reach your phone?

In other words, how much of the day do you have to walk to find your phone or you even have to search for it? And for the vast majority of people, the phone is there all the time. It's right there. It's functionally implanted. It may not be inside your head, but you allow it by having it right there to basically function that way.

We have access to more food than we could possibly eat, which was not historically the state for humans. Humans had to find food, and then they ate it, and then they had to find some more, and then they ate it, and so on. And hopefully, they found enough to stay alive, but we're not in that position anymore. We have too much food. And so our challenge is very different. It's how do you cut down on your intake? Otherwise, we could sit and just eat all day every day, and that would be not very healthy for us. So most people don't do that. And the same is now true, we're finding ourselves in this funny position where information used to be scarce. You had to go out and find it, and you had to try very hard. This was even true when I was a kid, and things are very different now.

And so one thing you could do is just as you might be a little bit more careful about what you consume dietarily, you also need to be careful about what you consume in terms of information. So I have friends who will say, I'm going to pick two or three news sources that I trust, that I've been reading for long enough to have a sense of whether I kind of agree with the tone of what they generally say. So maybe you buy a subscription to those three platforms online or maybe even ask for the paper, the physical newspaper to be delivered, and each day you open the paper, old school analog paper, and you page through it. And so what you're doing then is you're getting the information you need. You're trying a little bit harder to get it. It's not just coming up in front of you on this Twitter feed or whatever, but you are also curating your diet much more effectively. And so you're not consuming as much of the garbage that I think most of us consume. And we allow our eyeballs to just roam the pastures in front of us on social media platforms.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

If you look at, for example, an old Pathé newsreel, you can see people being seen by a camera for the first time. And it just makes me reflect on how much innocence we have lost.

ALTER

I teach an introduction to marketing class to undergrads and MBAs and PhD students and executive MBAs. We'll look at old newsreels, and we'll look at ads from the fifties, sixties, seventies, the dawn of TV, really. And we look at those ads, and we sort of laugh in a superior way because they look so naive. And you're right, there is something very humane about them. They're very straightforward. They don't seem to be trying too hard to convince you of anything. And if they do, they just seem so obvious now. There's no trickery there. There's no chicanery. It's right there in front of you. And I think people weren't jaded in the same way back then. They were just taking things at face value. They weren't bombarded.

I don't know how often ads were presented then Exactly, but I know there were fewer of them. And so you didn't encounter as many, and so you had more mental resources for them, so you actually listened to them. So a company might say, Here's our new bar of soap. It has these 10 benefits that make it better than the competition. There is no advertising like that today cuz no one's got time to listen to those 10 things. You just need to be bombarded by sight and sounds and the branding, and then you're like, Oh, that's the bar of soap for me.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

For you, what is that grounds you? What brings you back to your core?

ALTER

I lived in New York City for a long time and about five years ago, my wife and I, with our two then very, very young kids, decided we wanted to leave the city. And I love Central Park. I love the city. There's so much to love about it. I wanted more outdoors, and I wanted more nature. I wanted water and trees, and I wanted things that I couldn't only find in Central Park. I wanted it to be all around. And so we moved out to Connecticut where we live, not so far from the water. There is unbelievable beauty out here. I run almost every day or go for long walks. And so for me, being in natural environments is really critical to my welfare. It's how I grew up in Australia. It's something that I missed for a long time when I was in the heart of Manhattan. A lot of people don't feel that way, but for me, that's personally very important.

And so I have to commute to NYU, where I teach. It's a long way to go, but I'm willing to do that because day to day I get enough benefit - and my kids and my wife get enough benefit - from being in these naturally beautiful settings to be willing to do that, to sacrifice the magic of the city, which I still miss a little bit, for the groundedness of being in natural environments.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

Your forthcoming book is Anatomy of a Breakthrough. You mentioned this ability to perhaps have greater insights or even collaborate in a kind of vague way with artists of the past, people from the past or those loved ones who maybe we didn't get a chance to know, but we can kind of accumulate what we do know about them to make these predictions about what a conversation with them would be. That seems like a positive element of these assistive technologies.

ALTER

There are two parts to being able to commune with people who are not actually around physically or because they're just no longer around in time. One is that it's emotionally powerful, this idea of being able to bring people back, even if it's just AI versions of them. But if they're convincing AI versions, there's something really kind of magical about that, potentially, if it's done right. So that's the one thing.

The other thing from a creativity perspective is we know that more people around you is good for creativity. It's one of the axioms in thinking about creativity in general. You need time. An artist, a writer. I'm a writer. I need time on my own. I also paint and draw. I cannot do that with other people around. It's just my process. But before you get there, before you get to that point where you need that time alone, that space apart, for almost everyone being around other people is good. It's good for creativity. It's both about diversity of opinion and idea and just about having more - just more information, more thoughts, more ways of looking at the world. And some of the most profound research I've come across in preparing for this book suggested that it's better to be around people who are deeply incompetent than it is to be around no one, which I found very surprising.

I always thought, yeah, you want to surround yourself with people who are really good at the thing you're trying to do because it'll rub off on you, and you'll end up being better. You know, you'll pick up bits and pieces from them, but the really fascinating idea is that even people who do something worse than you do it are actually good for your creative process, which I hadn't really thought of much.

But there's some really robust evidence to that effect, which suggests that there's not much cost to bringing other people's brains into the creative process, and I think that's one potential use of screens and tech, AI, and VR tech, is that you can bring in more ideas and greater diversity into the way you think about any creative process.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

Since there's been so many events like the Facebook whistleblower recently, how she spoke out about the addictive methods they use. Do you think it all comes to a head at a certain point when the companies and the people creating this tech reach a moral threshold, if it becomes too all encompassing for society?

ALTER

When I was first interested in the topic, it was actually not that easy to sell a book on it. So publishers were convinced that we all loved tech, and they weren't convinced that we were critical of tech or that we should be critical of tech. They were like, Well, everyone loves these pieces of tech, these devices. Why would anyone write a book criticizing this? Which is almost impossible to believe. This is only seven or eight years ago. So that's one thing that's shifted is we as a population, I think, are much more critical and are much more thoughtful about our relationship to these devices. We were sort of uncritical, and we just allowed them into our lives for a long time.

And you’re on a committee organized by the World Economic Forum. Governance, of course, is very important. So what what suggestions were you putting forth?

ALTER

It's really interesting to me that around the world there are different levels of intervention from governments. You know, there are some countries that are much more, we'll use the US term, libertarian about technology. They say, it's up to the consumer. Even if it's hard, you just have to decide as a consumer what you want your kids to experience, and what you want to experience. If you don't want to use technology, don't download this particular app and figure out a way to just help yourself.

I think that's unrealistic at scale. I just know too much about the products that are being put out into the world and our ability as humans to resist them, to know that, to just rely on the bottom-up process of every consumer empowering him, or herself, is just unrealistic. The alternative is to go top-down.

And there are some governments, Western Europe, Northern Europe, East Asia, and to some extent Australia are the four of these, where the government is getting involved in saying, there are some things we don't want to happen when technology becomes a bigger part of our lives. And so there's legislation that says, for example, there are certain features that cannot be built into the apps that are used in this part of the world.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

Sometimes it’s hard to get in rooms with big tech. What were some of those questions you wanted to ask, if you could get in those rooms?

ALTER

Very similar to the question you just asked. What's next? Now, I, we always think about where we are as the destination, right? We look at phones and we're like, look at this device we've created. Now we're going to have to deal with this device and figure out how to manage it, and so on. Surely in 20 years, there's going to be something else because before phones, there was something else, and we couldn't imagine that phones would play such a big role in our lives. Then the iPad and the tablets came along, and we had Facebook, and then suddenly there was Instagram, and then suddenly there was Twitter, and suddenly there was Snapchat, and then there was TikTok. And, we are going to look back on these platforms at some point and they're going to seem quaint because they were so simple. Things are going to get more complicated. Now I want to know what that's going to look like. What does it mean for them to get more sophisticated, more difficult for us to resist? As the arms race for our attention grows and continues? What will it mean for us as consumers of these forms of tech? How can they become harder for us to resist when we already spend every spare minute of our day looking at the screen? So those are the kinds of questions I wanted to ask. Those are the abstract philosophical ones. The more, down-to-earth ones, if I was speaking to an executive from one of these companies, I would ask very specific questions about what's going on behind the curtain. What's happened in the last four or five years though, since writing the book, is that a lot of these people have come out of their own volition, and they've said a lot of what I was going to ask. So Sean Parker, one of the early investors in Facebook in November 2017 was giving an interview, and he basically said, Look, honestly, we've never really cared about your welfare. It's not that we want to hurt you, it's just that we don't care if we do. And what we really want is just to make sure that you spend as much time as possible on our platform so we can make as much money as possible through advertising. We've always wanted that. We've always been, some of us, a little bit squeamish about what that might do to you and your kids, but we are agnostic and are amoral. We don't care about that stuff. It's just about making money. And that's disarming to hear that from someone who's that senior and was there that early on. He's talking about what was going on at Facebook in 2004, so it's almost 20 years ago. And that was driving decisions that still have effects now almost 20 years later.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

And of course there are all these other developments like neural wetwear. It's one thing having tech on the outside. It's another thing getting kind of flawed, technology implanted. And you've actually created these very interesting charts where you've analyzed how much of our personal time is taken up by devices, but with implants there’s no escape. That would be like going into your dream time.

ALTER

People still bristle at the idea that they would allow devices to be planted inside their brains, right? Like if I said to you I've got a little syringe here, and I'm just going to inject this little thing into the base of your brain stem, and it's going to change your experience of the world for the good. If you're a creative, we can help you be more creative overnight. I could promise you all that sort of wonderful stuff. Almost everyone would say, I am deeply uncomfortable about allowing that to happen. We may become more comfortable with it over time. We're not that far away from that with our current devices because we allow them to be with us always.

They are shaping how we think and they are even shaping how we dream because we spend so much time engaged with them. And so if you are going to feed your brain during the waking hours a diet of all the crap that comes out of these phones, your dreams will also be in some sense reflecting what you've put in there during the day. It's not quite the same as shaping your dreams, but I think we're only a couple of steps shy of that now. So we've got to figure it out even before we get to that point. But yes, it could get a lot worse and a lot more intense, and a lot more invasive.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

As you think about the future and our current education models, and as you reflect on some teachers who were important to you, what would you like young people to know, preserve and remember?

ALTER

I think the most helpful education I ever had was not content. It was never like, here is a thing that's interesting. Here is an artist you need to know about. It was always a way of thinking about the world. It was a way of processing new information. And so I think that's something that's worth cultivating, and you don't get all that much time to do that. You get that when you're in school and if you go to university, you get that in university, but then you go about the business of living in the world, and you don't have as much time to do that. So I would say if you're asking yourself, what kinds of courses should I take or what kinds of people should I learn from? I think one of the things to ask yourself - Is this person teaching me a way of looking at the world that I can then take with me onto the next thing?

I want to know that there is a useful way to process new ideas and new things beause the world is going to evolve, and then you're going to be faced with novelty, and you're going to need to make sense of it. And I think that's at the heart of creativity - learning ways of doing things rather than what those actual things are that are in front of you.

So for me, that's very important. What are ways of thinking about the world that are useful to you that will bring on creativity, whatever other useful ends there are that are personally important to you? And that's always been, I think, the hallmark of the best educators and the best minds that I've come across. They have been people that kind of shift the way I process the world and the information I come across in the world.

This interview was conducted by Mia Funk and Clare Considine with the participation of collaborating universities and students. Associate Interviews Producer on this episode was Clare Considine. Digital Media Coordinators are Jacob A. Preisler and Megan Hegenbarth.

Mia Funk is an artist, interviewer and founder of The Creative Process & One Planet Podcast (Conversations about Climate Change & Environmental Solutions).