For nearly half a century, Richard “Dickie” Landry was at the center of the New York avant-garde. Born in the small Louisiana town of Cecilia in 1938, he began making pilgrimages to the city while still in his teens in search of the city’s most cutting edge gestures in jazz, and relaxed there not long after, falling in with a close knit community of artists and composers like Keith Sonnier, Philip Glass, Joan Jonas, Gordon Matt Clarke, Richard Serra, Robert Rauschenberg, Nancy Graves, Lawrence Weiner, Steve Reich, Jon Gibson, and Robert Wilson.

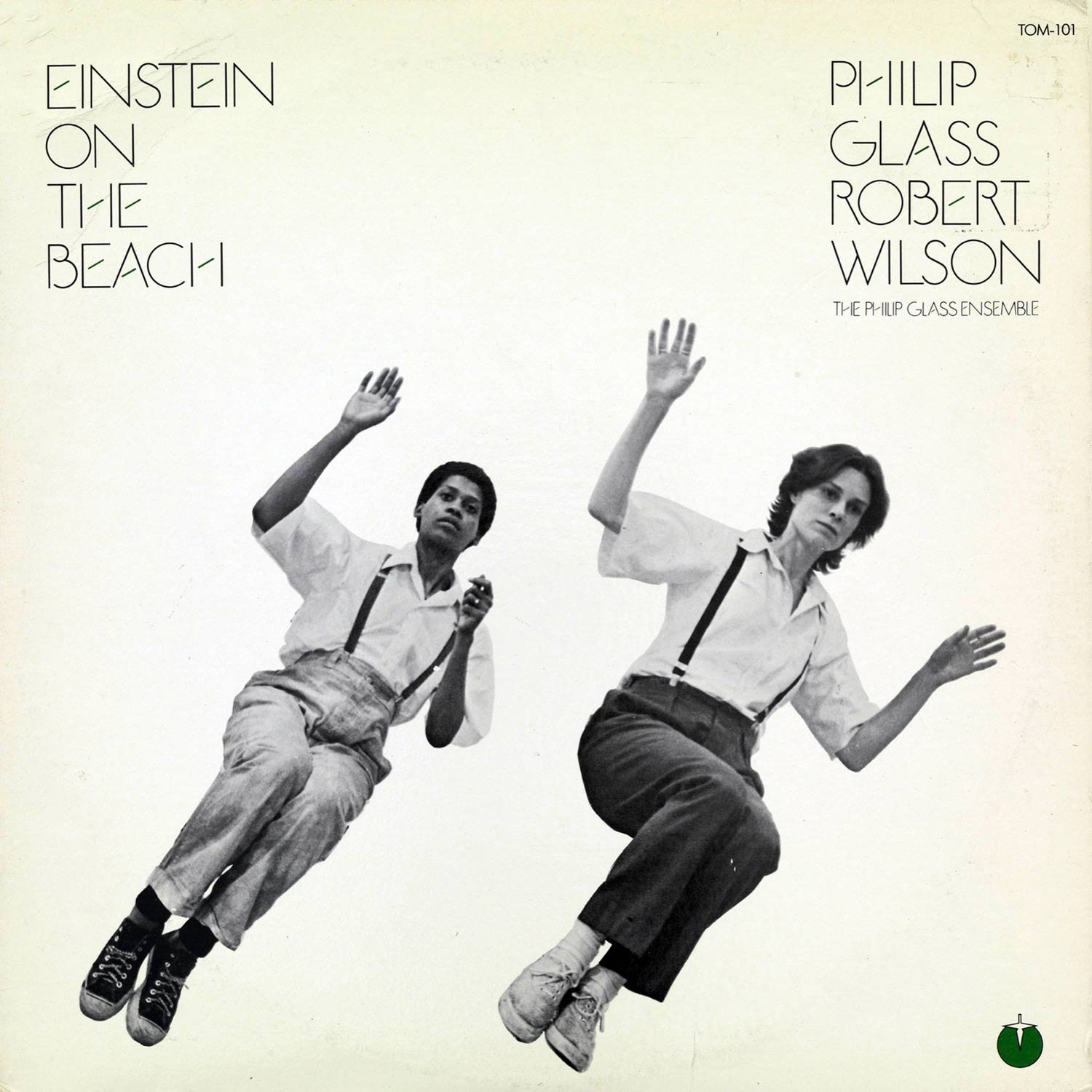

Landry remains one of the few artists of his generation who made important waves within numerous creative idioms. Having been trained from a young age on saxophone, not only is he a remarkably respected solo performer and bandleader, but he was an early and long-standing member of Philip Glass’ ensemble, playing on seminal records like Music With Changing Parts, Music in Similar Motion / Music in Fifths, Music in Twelve Parts, North Star, and Einstein on the Beach, and played with Talking Heads, Laurie Anderson, and jazz giants like Johnny Hammond, Gene Ammons, and Les McCann. He was also one of the most important photographic documenters of the New York Scene, until he left the city for his native Louisiana, following 9/11. Listen to his music on Unseen Worlds.

DICKIE LANDRY

I grew up in Cecilia, Louisiana. Born on November 16th, 1938. Very poor family. No electricity, no running water, heat by wood. My mother was a teacher, first grade and second grade. She taught for 40 years, died at 102 and a half, totally mentally together. My father was a foreman on jobs in Central and South America, building sugar can refineries. At the age of 13, my father came back and opened a dairy, but in the meantime growing up, there was not much to do except go to church. There was no movie theater, television, or anything else. We didn't have a radio. So my mother brought me to the church, St. Joseph's Church in Cecilia, to become an altar boy, to serve the priest for the mass and stuff.

I had three girl cousins who would come for a month every summer. And we had a great time together. In those days, those were my close friends, my cousins. So I realized that I liked girls. So as we were talking to the priest, the choir started singing in the back of the church up in the loft. And I turned around. It was all girls, and I was like, "Mama, I want to sing." So thanks to the women, this is how I began my musical career.

And my brother is a saxophone player also. He's eight years older than I am. And when the Korean War broke out, he joined the Air Force and was stationed in Waco, Texas, where Bob Wilson is from, and would send me records and jazz records and stuff. So when he came out of the service, he was playing in a society band, you know, for dances and weddings. And when I was 13 years old, he invited me to come to the club, and I had to go through the back door because I was underage. And that was my first professional job. I made $10 for four hours, and that was a lot of money in those days.

Einstein on the Beach, it's a masterpiece. America, in 1976, was to be celebrating its 200th year of existence, and Michel Guy, the French Minister of Culture, came to New York to offer a commission to Philip Glass and Robert Wilson to write an opera. This was the gift that France would give for America's two-hundredth anniversary. That was the first time I met Robert Wilson.

*

My son had died, and I had taken to two years to recover. So I went to New York. I had dinner with Laurie Anderson, and as I was getting up to leave, she said, "What are you doing in New York?" I said, "I'm looking for work." She said, "What are you doing next week?" I said, "Well, I'm supposed to be in Atlanta, Georgia doing a music film with David Byrne and Talking Heads. Well, what do you have?" She said, "I'm doing a piece next week at Brooklyn Academy of Music with Trisha Brown and Robert Rauschenberg, Set and Reset. Why don't you come? Bring your sax, we'll work it out then." Two weeks after that concert, Laurie's manager called and said, "Do you want to go on a 20-city tour of America with Laurie? Home of the Brave?" Of course, we did that. That was the beginning of the reconstruction of my career in New York through Laurie Anderson.

*

Well, look at tennis players where they hit the ball on one side of the court and next thing you know it's on the other side of the court. It’s all practice, practice, practice. That's what I tell people who say, "I want to learn how to play the saxophone or the flute or clarinet, or any instrument. I say, "Start practicing.”

*

The first painting I saw of what I had done, the finished painting was a real turn on. I mean, really heavy, like that painting was coming from my brain. It wasn't a photograph. It wasn't an image of something. It was coming from me, from this. That really, I mean, excited me more than when I first heard John Coltrane or Ornette Coleman. And it was like, Pow, this is what painting is about. It's about individual piece of work. It's not a photograph.

*

The way I became interested in art was in high school. I was graduating. What are you going to do? What are you going to do with your life? So one day I went to the library and was thumbing through Time magazine and turned the page, and there's a work of art by Robert Rauschenberg. And when I saw what he'd done and was getting international attention for, his pieces hanging in museums somewhere in the world, the light bulb went off in my head. I can be whatever I want. I don't have to be categorized. I'm free. Free...I get bored doing just one thing. People say, “Well, you can only have one stamp of what you do.” I didn't believe in that. I was just, you know, I liked everything I did."

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

I’m curious about how your music may have changed as you traveled, picking up on a vibe in the country?

LANDRY

I am who I am wherever I go.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

And they have to tune into you.

LANDRY

Exactly. I do what I do, and it's...how can I phrase this? I don't judge a country. I don't judge the people. I go there offering what I do. And that doesn't change. What I do doesn't change to fit the country or the people.

*

Some people ask me sometimes, "When you're painting, do you think about music? Or when you are playing, do you think about painting? Or your photographs?" It's totally separate. When I'm playing music, I'm playing music. When I'm painting, I'm painting. I'm not thinking about music. In fact, I don't listen to music when I'm painting. Photography is a whole technique, and you have to pay attention to what you're doing instead of thinking about something else. You've got to focus on the process at the moment, not dream of, Oh, I'm listening to a symphony...

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

Can you describe that level of concentration when you're improvising, which is at the same time loose and open and listening? How did you arrive at that?

LANDRY

That took a little time to organize in my head. I still have problems today. Some people call it stage fright. I don't know what it is, but I'm always right before a concert thinking, Why am I doing this? I should be doing this. I should be doing that. Why am I here? What am I going to do? And I walk up to the microphone, I'm still thinking this, and I start playing. And I'm still thinking, What am I doing here? Why, why, why? All the questions of how I'm going to sustain playing for 45 minutes or an hour, and I'm still playing and playing. And then all of a sudden I go, Well, Mr. Landry, you've got people sitting in the audience. You're getting paid for this. So enjoy yourself. So the next thing I know, the concert is over, and I don't know where I've been.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

It's losing time.

LANDRY

Yeah. In time, in a way. Some people might call that nirvana. I'm not sure.

This interview was conducted by Mia Funk and with the participation of collaborating universities and students. Associate Interviews Producer on this episode was Daisy O'Dwyer. Digital Media Coordinators are Jacob A. Preisler and Megan Hegenbarth.

Mia Funk is an artist, interviewer and founder of The Creative Process & One Planet Podcast (Conversations about Climate Change & Environmental Solutions).

Music on this episode courtesy of Dickie Landry:

E-mu & Alto Saxophone composed by D.L. for Robert Wilson's production of 1433 The Grand Voyage based on the story of Zheng He. Premier National Theater Taipei, Taiwan 2009

“Gloria” for Robert Wilson’s Oedipus Rex

Philip Glass’ Einstein on the Beach. Original recording on Tomato Records 1977. D.L. on flute

"Are Years What", Phillip Glass. Composed for D.L. playing 3 soprano saxophones. On his LP "North Star”, 1977

Swing Kings 1965, D.L. on flute

“Home of the Brave” on the Late Show with Laurie Anderson

"Taideco" Zydeco, for Wilson's production of 1433 Cedric Watson, Jermain Prejean, D.L.

“Ghosties” from Dickie Landry Solo

"It Keeps Rainin'", Robert Plant with Lil' Band O' Gold