Michel Faber’s most recent novel, The Book of Strange New Things, won a 2015 Saltire Book of the Year Award. He has written seven other books, including the highly acclaimed The Crimson Petal and the White, The Fahrenheit Twins and the Whitbread-shortlisted novel Under the Skin. The Apple, based on characters in The Crimson Petal and the White, was published in 2006. He has also written two novellas, The Hundred and Ninety-Nine Steps (2001) and The Courage Consort (2002), and has won several short-story awards, including the Neil Gunn, Ian St James and Macallan. Born in Holland, brought up in Australia, he now lives in the Scottish Highlands.

This is an abridgement of 7,000 word interview which will be published across a network of university and national literary magazines in the coming months.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

The Crimson Petal and the White begins with a very present, visceral passage written in second person, where you transport readers into the skin of Sugar, a Victorian prostitute, walking the cobbled streets of Church Lane, the sights and smells and public drunkenness as she makes her first uncertain steps into her new life. Likewise in Under the Skin, from the beginning you pay close attention to ground the details of Isserley’s long drives through the Highlands searching for lone hitchhikers, giving a vivid sense of the beauty among the littered asphalt, as her eyes strain to find her next victim. Most recently, The Book of Strange New Things begins by grounding readers in a description of another voyage––that of a missionary, Peter, leaving his wife on Earth to minister to strange beings called the Oasans on another planet.

Can you share your reasons for beginning those novels where you did?

MICHEL FABER

I'm not keen on the late-20th century fashion for starting a narrative "in the middle of the action" with a thrilling but rather puzzling event, then backtracking to fill in the context that led to this scene. It seems like a cheap trick to me, an insult to the reader's intelligence, implying that nowadays nobody has the patience to engage with a story unless it starts with fireworks and mayhem. The challenge for a serious writer is to begin a story in a way that isn't crass but that will engage the reader's curiosity. At the start of The Crimson Petal, I make the reader feel like an alien who's landed in Victorian London and who urgently needs to find a roof over their head. At the start of Under The Skin, I plant just one little question in the reader's head (Why is this woman looking for hitchhikers?) and then allow that question to hang there while distracting you with the beauty of the Scottish landscape. At the start of The Book of Strange New Things, we meet this married couple who are clearly committed Christians and yet they're going to have sex in the back seat of their car (which is not something we normally imagine Christians doing), and, despite the fact that they obviously love each other, it appears he's leaving her. This odd combination of factors makes the reader need to know (I hope) how all this fits together. But in each case, the novel starts at the very beginning; it's utterly linear.

I don't object to non-linear narratives per se. I'm a big William Burroughs fan, and his books are in almost random narrative order. But my books already demand quite a lot of the reader in terms of the issues I invite you to confront and the emotional states I put you in, and I don't think it would be fair or helpful to add structural tricksiness into that equation.

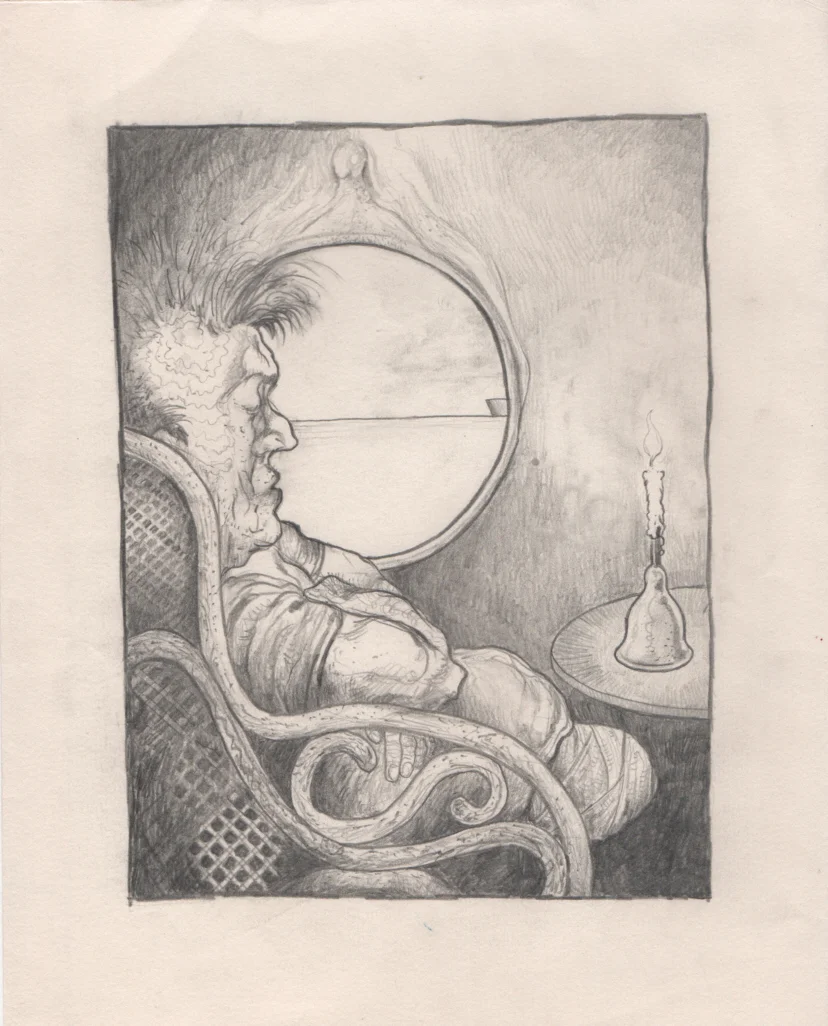

Portrait of Michel and Eva by Mia Funk

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

Your approach reminds me of some of the techniques used by actors, asking themselves questions, sense memory, the stitching together of small details to build a character. How do you decide on your P.O.V. and where is the best place to begin?

FABER

Well, you're talking about my novelistic working method in the present tense and The Book of Strange New Things was my final novel, so I'm looking back on the books in a retrospective overview. And I see that the only novel that was told in the first person was The Ship Of Fools, which I decided to leave unpublished. I've written a number of short stories from a first-person POV but I guess with novels I felt that this was too restrictive. What worked for me was a third-person approach that was somewhat suffused with the personality of the character. So I'd be free to describe and note things that my characters would not necessarily be describing or noting, but the emotional texture of the prose would be coloured by their attitudes and limitations.

In each of the novels, I negotiated this slightly differently. In Under The Skin, everything is channelled through Isserley's sensibility except for those brief, almost ritualised scenes where a hitchhiker gets into the car with her and we are given italicised access to his thoughts and how he perceives Isserley. In The Book of Strange New Things, we get the full technicolour authorial picture (suffused with Peter's sensibility) but we also get a grossly inferior version of those same experiences when Peter attempts to describe them to his wife in his letters. In The Crimson Petal, I considered having the entire novel filtered through Sugar's sensibility but decided that would become oppressive over 800+ pages. So, the third-person prose is coloured by the sensibility of whichever character it is principally dealing with at any point. I could talk about the intricacies of this process for hours, giving examples, but suffice to say that it was handled very carefully. It was important not to switch suddenly from one sensibility to another, as this would have called attention to the art as well as possibly causing confusion. So, I used action-free, dialogue-free connective passages as a way of smoothing the transitions from one character's reality to another's, to give you time to adjust to no longer getting emotional cues from the character you'd been with. As soon as I judged that you would feel yourself to be on "neutral" narrative ground, ie, no longer in the spirit of a particular character, I would then take you into the sensibility of the next character.

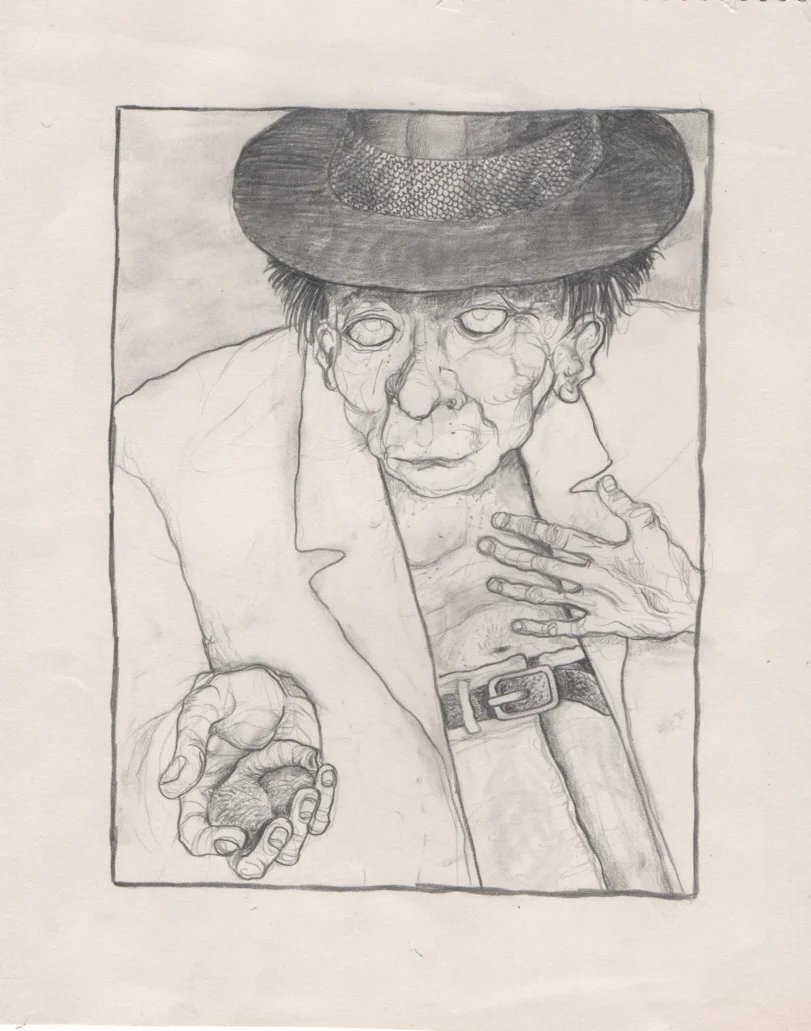

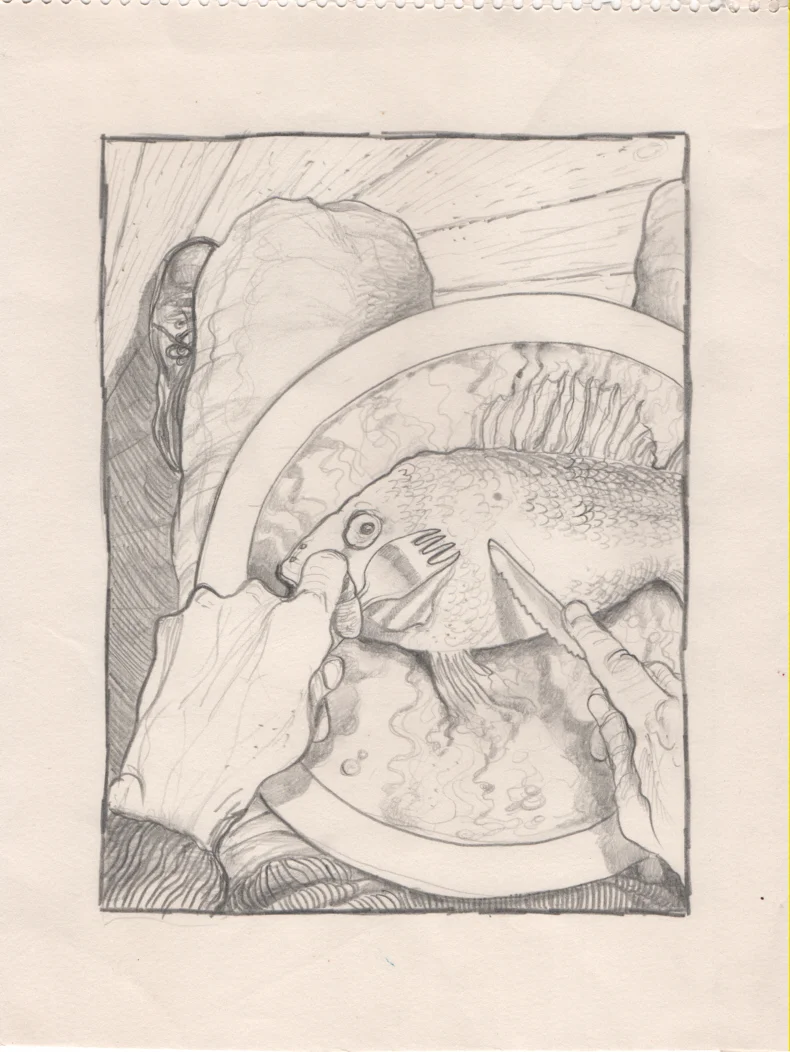

artworks from faber's unpublished graphic novel The ship of fools. ILLUSTRATIONS BY MICHEL FABER.

ABOVE: The albatross

The Look Out

The Smiling Man

The Fish

Find us on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Google Podcasts, Podcast Addict, Pocket Casts, Breaker, Castbox, TuneIn, Overcast, RadioPublic, Podtail, and Listen Notes, among others.

Mia Funk is an artist, interviewer and founder of The Creative Process.

Selected French translations:

En regardant les livres en prenant du recul et de la hauteur, je n’ai écrit des nouvelles qu’à la première personne (en caméra subjective) mais je suppose que cela me paraissait trop restrictif pour les romans. Je trouvais que ce qui fonctionnait était une approche à la troisième personne qui prenait parfois le pas sur la personnalité du personnage. Alors j’étais libre de décrire et de constater des choses que mes personnages ne décriraient ou ne constateraient pas forcément, mais la texture émotionnelle de la prose serait teinte de leurs attitudes et restrictions. (…) Il était important de ne pas passer d’un coup d’une sensibilité à une autre, car cela aurait aussi bien attiré l’attention sur le procédé que cela aurait pu créer de la confusion. Alors, j’ai utilisé des passages de transition sans action et sans dialogue et comme moyen d’effectuer en douceur les transitions de la réalité d’un personnage à un autre, pour vous donner le temps de vous ajuster à ne plus recevoir les répliques du personnage avec lequel vous étiez. Dès que j’ai estimé que vous auriez l’impression d’être sur le terrain « neutre » de la narration, c’est-à-dire, non plus dans la tête d’un personnage particulier, je vous mène ensuite vers la sensibilité du prochain personnage.

[...]

La créativité est utile et réconfortante. Je ne sais pas si les écrivains de fiction sont des gens plus intellectuels que ceux qui aiment jardiner ou ceux qui servent la soupe populaire aux SDF. N’importe quelle activité qui établit qu’il y ait une quelconque utilité à faire en sorte que les choses se réalisent, malgré la mort inévitable, la déchéance, l’effacement des empires et l’éventuelle extinction de notre système solaire, est intellectuelle, vous ne trouvez pas ?

translated from English by Olivia Reulier