By Cécile Oumhani

After we moved from the downtown apartment, I asked her about her wooden palette, studded with brightly colored planets that seemed to open on an infinite array of possibilities. I also mentioned one of her black-lacquered metal watercolor boxes. It carried lines of white porcelain pans. She replied that she would not paint anymore. Never again.

I kept asking, as children do, until she indulged me. On and on, I repeated she had to show me. I longed to see her paint. And one day, she fetched her easel from the cellar. She unfolded it in the living-room, because the house was too small for her to have a room of her own. It was several years before she had a workshop built. Her easel stayed where she had placed it for a long time.

The first canvas she painted in my presence was a portrait. My hair is short, just the way she used to cut it for me. I am wearing a red woolen cardigan knitted by my French grandmother. I had to sit for her, but I did not mind, far from it. I was so keen to see her at work.

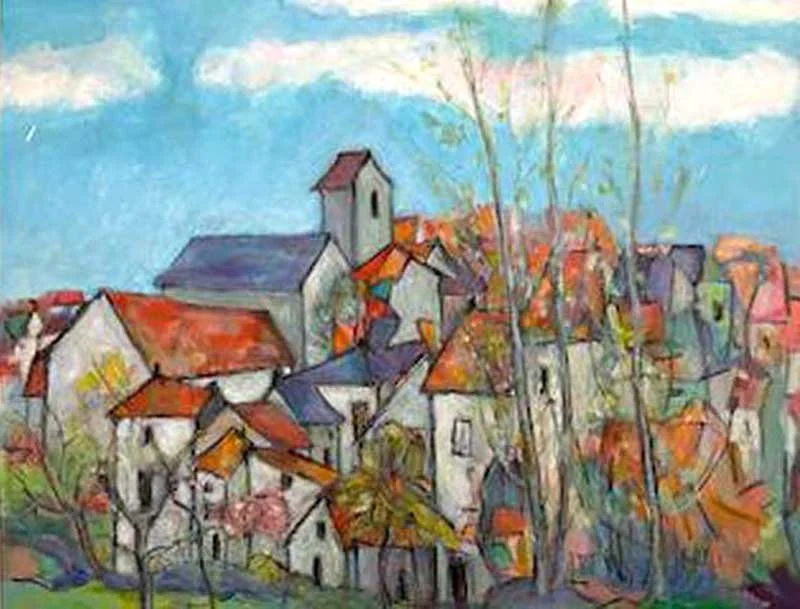

Then she went on painting still lifes, landscapes she sketched when our father took us for drives in the vicinity. One of those small Romanesque churches scattered in the countryside, the Marne Valley, or a village nestled among vine slopes… And she continued in the living room. Lines and touches of color gradually came to life on the rectangle of white canvas stretched on its frame. I always wondered at the length of time it took before a painting that satisfied her emerged. In my mind’s eye, I can still see the sun filtering through the branches of the weeping-willow in front of the living-room. Its rays lit up the canvasses on her easel. And when the breeze blew in the leaves, images entered our house with their shadows, and nothing would stop them. Moving and fleeting, their contours and what my mother was painting overlapped.

She used to say that you needed an atrium window in an artist’s workshop. And when hers was built, it had a skylight, where she painted. I heard the rain pattering on the glass. But neither wind nor hail could distract her from the work she carried on, in her long painter’s coat. The taupe-colored material was so soft to the touch it was almost like velvet. The brush in her hand was a magic wand lost in the real world. It fascinated me.

Can you say absence and separation with colors? So many written words traveled back and forth the ocean between us and her family. I believe these blue ink words drew a path for me. I have never forgotten their smell, blended with that of the blue paper. Deep and slightly sweet, it is still there inside me. Through it, I inhaled a place steeped in mystery. It was a whole country I was breathing in.

“A letter from Canada! » my mother would exclaim, as she walked up the path from the mailbox at the gate to our house. It ran under a cherry-tree, whose fruits were deliciously tart. Sitting at the kitchen-table, she leant over the paper with devotion. I listened as she read. I could hear cracks in her voice. Pieces of everyday life that were already a fortnight-old, over there, across the Atlantic… Bits of sentences jotted down feverishly, at different moments in the same day sometimes. Letters that were interrupted, then resumed, in the afternoon or in the evening. By my grandmother, one or the other of my aunts. They had added a few words, changed inks, scribbled with a Bic pen or a pencil. Sentences that were barely ended, exclamation marks for everyday events they wanted to share. There had been that cramique and its taste of warm bread and crunchy sugar, or that walk by the lake. And when we knew in Europe, it would be just like we had all been together, despite that rotten ocean. It would be like we had eaten our slice of cramique or had all admired the shades of the water, as they changed according to the time or the season… This through the sheer magic of what was noted down on paper, then slipped into an envelope. And what did she say with her colors that she did not express with the words she wrote back to her family in Canada? And did she say anything with her colors? No, it was not a mere excess of words that would have come forth as if from tubes of paint to find their place on her paintings. It was quite different. Images, shadows, and reflections lay in the bottom of her eyes, and I could not see them with her. The warm red of sanguine, a fruit gorged with sun, on sheets rough to the touch, gave life to places and landscapes, unknown to me. Was it Gibraltar, where she had stayed at one point during the war? There were also parts of Andalusia she had explored, carrying her sketchbooks and a bottle of India ink. I found that life had a thousand and one windows, beyond those we push open at home every morning.

Her charcoal sticks sometimes crumbled, and their fine black dust smudged the paper, if one was not careful. Territories veiled with darkness, foliage, and figures… The movement of her hand endlessly unfolded what I dreamed of visiting. Did they even exist anywhere on the earth’s surface, even if I knew they must have been shaped by her migrations across the planet, from her earliest childhood? When you go from one continent to another, forever leaving beings and things behind, you surely develop extraordinary faculties to create new lands.

Extract from "Ma mère et la peinture / Meine Mutter und die Malerei", German translation by Tanja Langer, Bübül Verlag Berlin, 2024

Translated from French by the author

Ma mère et la peinture

Une fois que nous eûmes quitté l’appartement au centre de la ville, je l’avais questionnée sur une palette de bois constellée de planètes aux couleurs vives qui me semblaient porteuses de mille possibles. Je lui avais aussi parlé d’une de ses boîtes d’aquarelles en métal noir. Des godets de porcelaine y étaient alignés. Elle m’avait répondu qu’elle ne peindrait plus maintenant. Plus jamais.

J’avais été insistante, comme les enfants savent l’être, jusqu’à obtenir satisfaction. Je lui avais répété qu’il fallait qu’elle me montre comment on faisait. Je voulais tellement la voir peindre. Et un jour, elle était allée chercher son chevalet à la cave. Elle l’avait déplié dans le salon, parce que la maison était trop petite pour qu’elle y ait une pièce à elle. Il s’est écoulé plusieurs années avant qu’elle ne construise son atelier. Son chevalet est longtemps resté là où elle l’avait placé ce jour-là. La première toile qu’elle ait peinte en ma présence était un portrait de moi. J’ai les cheveux courts, tels qu’elle avait l’habitude de me les couper. Je porte une petite veste de laine rouge que m’avait tricotée ma grand-mère française. Il m’avait fallu poser, mais cela ne m’avait pas pesé, bien au contraire. J’étais trop curieuse de l’observer à l’œuvre. Puis elle a continué avec des natures mortes, des paysages qu’elle ébauchait, quand mon père nous emmenait en excursion dans les environs. Une de ces petites églises romanes égrenées dans la campagne, la vallée de la Marne ou encore un village niché parmi des coteaux plantés de vignes… Et elle continuait dans le salon. Traits et touches de couleur venaient peupler peu à peu le rectangle de tissu blanc tendu sur son cadre. Je m’étonnais toujours de tout ce temps passé avant qu’émerge une peinture dont elle était satisfaite. Je revois le soleil tamisé par les branches du saule pleureur devant le salon. Ses rayons inondaient les toiles sur son chevalet. Et lorsque la brise agitait les feuillages, une image s’invitait chez nous avec les ombres, toutes frontières abolies. Mouvante et fugace, ses contours se superposaient à celle que peignait ma mère.

Elle disait qu’un véritable atelier de peintre devait avoir une verrière. Et celui qu’elle fit bâtir eut un puits de lumière sous lequel elle travaillait. On entendait la pluie y tambouriner. Mais ni le vent ni la grêle ne l’auraient détournée de ce qu’elle poursuivait, habillée de sa longue blouse de peintre. Son tissu taupe était si doux au toucher, qu’il était presque velouté. Le pinceau dans sa main était une baguette magique égarée au sein du réel. Il me fascinait.

Dit-on l’absence et l’éloignement avec les couleurs ? Tant de mots écrits circulaient d’une rive à l’autre de l’océan qui la séparait des siens. Je crois que ces mots d’encre bleue ont tracé pour moi un chemin. Je n’en ai pas oublié l’odeur, mêlée à celle du papier, bleu lui aussi. Profonde et légèrement sucrée, elle m’imprègne jusqu’à aujourd’hui. À travers elle, j’inhalais un lieu empreint de tout son mystère. C’était un pays que je respirais à pleins poumons.

Une lettre du Canada !, s’exclamait ma mère, en remontant le sentier qui menait de la boîte à l’entrée du jardin jusqu’à notre maison. Il passait sous un cerisier dont les fruits étaient délicieusement aigres. Assise à la table de la cuisine, elle dépliait les feuillets avec recueillement. Je l’écoutais lire. J’entendais des fêlures dans sa voix. Les bribes d’un quotidien déjà vieux d’une quinzaine de jours, là-bas de l’autre côté de l’Atlantique… Des bouts de phrase jetés fébrilement, parfois à des heures différentes de la journée. Une lettre interrompue, puis reprise plus tard, l’après-midi ou le soir. Par ma grand-mère, par l’une ou l’autre de mes tantes. Elles avaient rajouté quelques mots, changé d’encre, griffonné au Bic rouge ou au crayon de mine. Des bouts de phrase, des points d’exclamation pour des gestes ordinaires qu’elles tenaient à raconter. Il y avait eu ce cramique, la saveur du pain chaud et le sucre qui craquait sous la dent, ou encore cette promenade au bord du lac. Et quand nous le saurions en Europe, ce serait comme si nous avions été tous ensemble, malgré ce fichu océan. Nous aurions nous aussi bel et bien mangé notre part de cramique ou admiré avec eux les nuances de l’eau qui changeaient selon l’heure ou la saison… Tout cela par la saisissante magie de ce qui avait été mis sur le papier, puis glissé dans une enveloppe. Alors que disait-elle avec ses couleurs qu’elle n’exprimait pas avec les mots qu’elle écrivait en réponse à la famille au Canada ?

Et disait-elle quoi que ce soit avec ses couleurs ? Non, ce n’était pas un simple surplus de mots qui jaillissait de ses tubes de peinture pour se déplacer sur un de ses tableaux. Il s’agissait de bien autre chose. Des images, des ombres et des reflets habitaient le fond de ses yeux, sans que je les voie avec elle. La sanguine chaude, un fruit gorgé de soleil sur une de ses feuilles si rêches au doigt, rendait vie à des lieux et des paysages qui m’étaient inconnus. Peut-être Gibraltar où elle avait séjourné pendant la guerre ? Il y avait aussi ces régions d’Andalousie qu’elle avait explorées, ses carnets et une bouteille d’encre de chine avec elle. Je découvrais que la vie avait mille fenêtres, au-delà de celles qu’on ouvrait le matin chez nous à la maison. Les bâtons de fusain s’effritaient quelquefois et leur fine poudre noire assombrissait le papier, si on n’y prenait garde. Des espaces voilés de nuit, des ramures et des silhouettes… Le mouvement de sa main déployait à l’infini ce que je rêvais de visiter. Existaient-ils quelque part à la surface de la terre, même si je me doutais qu’ils étaient nourris de ses migrations à travers la planète, dès la plus petite enfance ? À aller ainsi d’un continent à un autre, à devoir laisser derrière soi des êtres et des choses, on doit développer d’extraordinaires facultés à se créer de nouvelles contrées, sans en être conscient.

Extrait de "Ma mère et la peinture/Meine Mutter und die Malerei", traduction allemande de Tanja Langer, Bübül Verlag Berlin, 2024

The Importance of Arts, Culture & The Creative Process

Arts and Culture are essential in our lives. I often think of people who survived extreme situations, simply because they kept reminiscing a painting, a poem... It has always moved me to remember them, because it is a testimony of the almost magical power of Arts and Culture. This project immediately called my attention because it brings so many people together from around the world. It has almost become a stereotype to say that our planet is going through a crisis. I firmly believe Arts and Culture have a role to play today. They are a beacon of hope.

What was the inspiration for your creative work?

Bübül Verlag in Berlin is preparing a translation of an earlier book of mine on writing, "À fleur de mots, la passion de l'écriture", published in 2004 by Chèvre-feuille Étoilée in France. My German editor asked me if I could write another text devoted to my mother, whose work as an artist had a great role in my life. In a way, I inherited the ink of my words from the colors of her paints. In the end, it became a short book of its own, an introduction to the translation of the earlier essay on writing.

Tell us something about the natural world that you love and don’t wish to lose. What are your thoughts on the kind of world we are leaving for the next generation?

I need to be in the midst of nature to write. I need to feel the presence of wild animals, to gaze at the sky above me, to listen to all the sounds of nature, to all its various shades of silence. Developing an awareness of nature's inhabitants brings me closer to a position where to think, where to observe, far away from the distortions of artificial forms of life. I am deeply concerned about the world future generations will inherit. Will they be able to experience the presence of trees around them as I have done, ever since I was a child? Will they be able to hear the silent voices of nature, those that take us back to the beginnings of our world? We should remember that the earth does not belong to us but to the future generations.