Lee Jaffe, a cross-disciplinary visual artist, musician, and poet, took photos of his friend, Jean-Michel Basquiat, when they traveled abroad in 1983. As a photographer, Jaffe had a connection to Basquiat, and their time spent together resulted in an archive of imagery that captured one of the art world’s true legends through an unfiltered and authentic lens.

“For me, watching him [Jean-Michel] paint reminded me of the times I would sit and play harmonica while Bob Marley, with his acoustic guitar, would be writing songs that were eventually to become classics,” Jaffe says. “With Jean and Bob, it seemed like they were channeling inspiration coming from an otherworldly place.”

Basquiat and Jaffe connected over reggae music. It was the early 1980s in New York. Jaffe had been a member of Bob Marley’s band, producer on Peter Tosh’s first solo album. and collaborated with art world figures Helio Oiticica, Gordon Matta Clark, and Vito Acconci. Jaffe is the author of Jean-Michel Basquiat: Crossroads.

LEE JAFFE

Jean-Michel Basquiat's combination of words and images, this visual poetry, just from a cultural standpoint has been so important. When I met him in 1983, black people were not allowed in the art market, pretty much. And you see that he broke down this barrier, which opened the door for all this multiculturalism within the art market. And you can't diminish the importance of that at all. It's helped to give a voice and an audience to all these incredible artists that might not have had that.

*

So I could be in his studio, and he could be carrying on a conversation, and there'd be music, and he wouldn't stop painting, which was really exciting. I mean, there's all this stuff going on, and then you're watching it, this masterpiece. And I played with Bob Marley. I played in his band, and I was living in his house for three years in Jamaica before he became this big thing. And we were struggling to find an audience, but I was a harmonica player, and I would sit with him while he was on acoustic guitar. And he'd be making up these songs. It just seemed like it was coming from some otherworldly place, this incredible inspiration. It was like, I would just be shaky. I'd be like playing harmonica, and I didn't know whether I should stop because it was just so brillian,t or I better keep going not to lose, not to interrupt his feeling. And watching Jean-Michel paint. It was like that. It was like Bob Marley making a song. I have to tell you, I felt like I was witnessing these cultural events, and I just happened to be there. I was just like, Wow, playing harmonica. I'm not the best harmonica player, but I'm okay. But I happened to be there.

*

For Basquiat, the context of Jamaican music at the time of the seventies and early eighties was definitely an influence. And then jazz, of course, which I don't think has been explored enough. When Abstract Expressionism was starting to happen in New York, many of those painters used to go to the jazz clubs to see, you know, Charlie Parker and then Coltrane and Pharoah Sanders. And that looks like, to me, that had to be the biggest influence on Abstract Expressionism because that's what was happening in New York. They were going to hear that music, and that music was so innovative, the level of proficiency on these classical instruments and then this breaking down of Western classical musical tradition. And those musicians started to appropriate music from other cultures.

You can see how Jean-Michel was so influenced by those musicians. And there's a fantastic show in New York now called King Pleasure, which comes from the King Pleasure song. And it's all about scat singing. It's a pretty terrific show. Sir David Adjaye designed the space. It's pretty great.

Images courtesy of Lee Jaffe

Around 11 a.m. one morning in late March of 1984, Jean-Michel phoned and asked if I could come by Mary Boone Gallery. Mary was doing a small catalogue for his upcoming exhibition in May and wanted his portrait for the back cover.

Jean-Michel Basquiat: painting in St. Moritz, 1983

Jean-Michel Basquiat on the bullet train tokyo to Kyoto: 1983

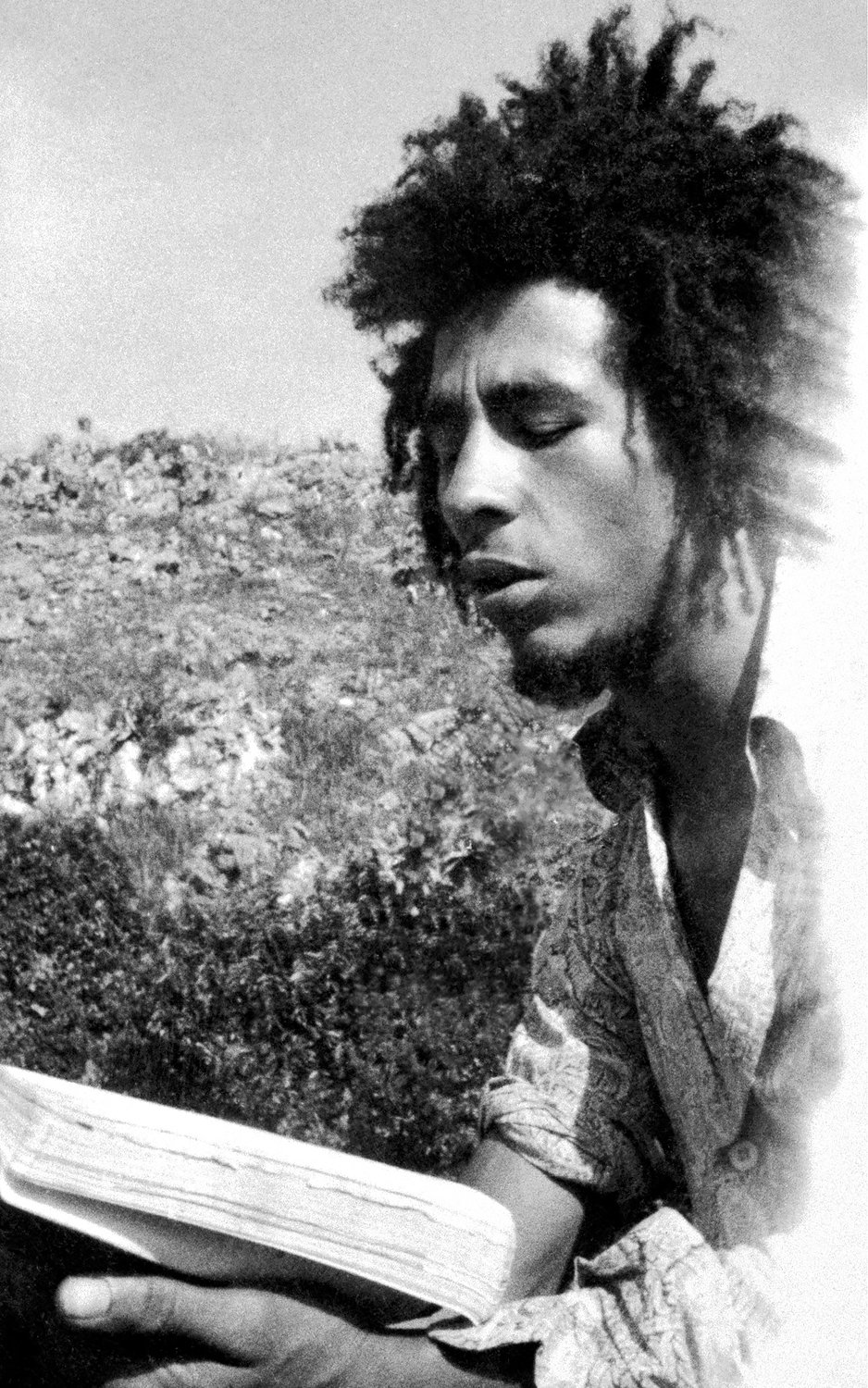

Bob Marley reading the Bible in front of the house where he was born, in the tiny village of Nine Mile in the mountains of St. Ann Parish, Jamaica

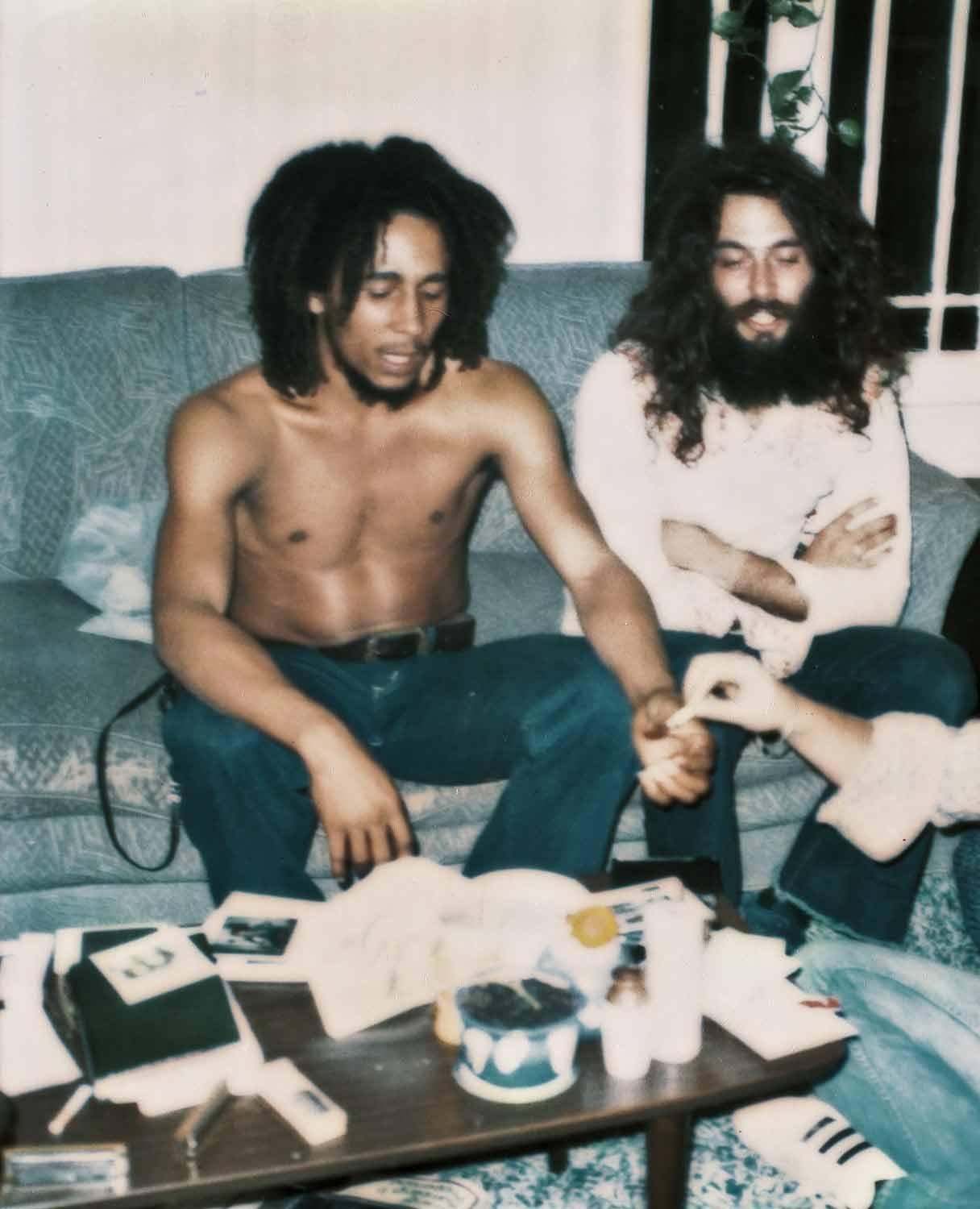

The Chelsea Hotel was within walking distance to Max’s and probably the only hotel where the manager, Stanley Bard, wouldn’t hassle anyone about smoking herb. With our minimal budget we stayed two in a room. I booked a one-bedroom suite for Bob and myself, as it had a tiny kitchenette and we had brought along our own cook. I slept on the foldout couch in the “living room.”

JAFFE

Well, it was alive. It was alive, immediate. It was visceral. And that experience of arriving in Kingston and hearing the music coming out of this shack – I mean, I didn't know absolutely that slaves had lived there. I was just arriving in Jamaica. This was all new. I didn't know anything about it, although I had seen this movie, The Harder They Come, this Jamaican movie that was Jamaican-produced. Chris Blackwell the Island Records founder produced it with Jamaican director Perry Henzell. And it was very much about colonialism and Rasta. It was my introduction to Rasta culture. So I had had a little bit of an inauguration into that from seeing that movie, but still arriving and hearing this... It was one thing to hear it on a cassette, which was overpowering. I mean, when I first heard that cassette, and the first song is "Concrete Jungle", it was the first Wailer's album was before Peter Tosh and Bunny Wailer left. And they were just called the Wailers, not Bob Marley and the Wailers. And the first song was "Concrete Jungle." The impact. The idea of "Concrete Jungle." I mean, that's so crucial because it starts off:

No sun will shine in my day today

The high yellow moon won′t come out to play

...In this here concrete jungle...where the living is hardest.

I was like, Oh my God, this is like the most genius thing I ever heard. And it's so relevant now, sadly. I mean, we're 50 years from when I first heard that. It's crazy. That song can't be any less relevant now than it was then.

*

And it was a time of great political repression. People on the left were disappearing. There was group of artists and musicians and writers who were creating things against the military government in Brazil. When I arrived in Rio in 1969, Caetano Veloso and Gilberto Gil, they had been imprisoned. They were in exile. They were let out of prison on condition they would leave the country. They were living in England. It was dangerous to be an artist saying anything against the government. And it was the time of the Vietnam War, towards the end of the Civil Rights Movement. I mean, it's never really ended, but...

there were the assassinations of all the Black Panthers and Malcolm X and Martin, and then RFK in '68, which very much pushed me into - I mean, I wanted to travel, I wanted to find out what the world was like, but - it was kind of a last straw when RFK was assassinated because then it was like, there is no law. The United States has no law. If there's political opposition, you'll just die. And then I was in Brazil, and it was very palpable. There was no disguise. There was no veneer.

*

I remember in the early 2000s, we had so much hope for the internet that it was going to democratize the distribution of music, especially when file sharing started. We said, Oh, wow. This is great. At that time, there were five major record companies, and then they conspired with MTV to give MTV all this free, big production content, and you couldn't really sell a lot of records unless you were on MTV. And unless you had this big budget for this video. And it started, artists were exploited from the beginning of radio. So I thought, Oh wow, now we're going to have file sharing, and we have the internet, and there's going to be all this information. This is going to transform the world. We're going to have this incredible end of poverty. And instead, we get Fascism. We get Bolsonaro, and it's really scary. On the other hand. listening to some of your podcasts, which I've been doing a lot recently. It's really pushed me to try to be optimistic because the pessimism is very oppressive. It makes me not want to work. So I'm really pushing myself to be consciously optimistic.

*

After I moved to Los Angles in 1986,

it was difficult for me to reach Jean-Michel.

I would call him weekly but couldn’t get through.

On my few trips to New York, I would stop by

his place on Great Jones Street and ring his

bell but he never answered.

I try to stop myself from thinking what

great art Jean-Michel would have made.

He had said he was interested in making movies.

Of course, they would have been amazing.

– Lee Jaffe

This interview was conducted by Mia Funk with the participation of collaborating universities and students. Associate Interviews Producer on this podcast was Colette Gauthier. Digital Media Coordinators are Jacob A. Preisler and Megan Hegenbarth.

Mia Funk is an artist, interviewer and founder of The Creative Process & One Planet Podcast (Conversations about Climate Change & Environmental Solutions).