Leopoldo Goût is an established artist, writer, and filmmaker who works across mediums to capture the ephemeral: an abstract and figurative clash with memory and humanity. Born in Mexico City, Goût grew up among poets, musicians, explorers, activists, filmmakers, scientists, and visual artists. Their stories and ideas inspired Goût, who quickly became part of that community. He embarked on numerous artistic pursuits: painting, drawing, sculpture, filmmaking, digital art, soundscapes, performance, and more. He studied in London at the renowned Central Saint Martins School of Art through a full scholarship from the Mexican Center for the Arts and the British Council. He also won the Erasmus scholarship, despite not being European. “I want to emulate and echo that fleeting moment when you wake from an intensely vivid dream, but immediately those images and senses start to dissipate,” Goût says. “I believe my work lives in that ephemeral space. Now you see it, now you don’t.” All his projects, including award-winning films and novels, influence each other in unexpected ways. Goût’s perspective is a confluence of the modern and ancient, order and disorder, and speaks to a wide audience. @leopoldoleopoldo

You born and raised in Mexico City. How did it influence your art and your thinking about the world? Mexico City—a maddening, sprawling organism of concrete and spirit. I grew up in a small apartment overflowing with books, art, and the kind of people who turned dinners into salons: poets, painters, revolutionaries, dreamers. My mother raised us in that creative chaos. I inhaled it like oxygen.

Even as a kid, I had this strange, unshakable clarity: we were living on top of another city—Tenochtitlan. The ancient Aztec capital wasn’t just buried beneath us; it pulsed through the cracks in the pavement. That revelation, at six years old, cracked my mind open. A city built on a city, a culture layered on another—that haunting, beautiful contradiction became the architecture of my thinking. It still is.

My third-grade teacher once wrote: “Leopoldo is bright and talented, but unfortunately, he will never amount to much—he only draws little pictures and writes strange stories.”

I’m still that kid. Still making strange pictures. Still writing the stories. Only now, I’ve played with many more mediums—always searching for my inner adult, while holding tight to the wild side inside who saw the ancient city under his feet.

When did you first fall in love with art and realize you wanted to be an artist? For you, what is the importance of the arts? Making art has always been my most natural state—the only place I feel truly at home making it, even when it's painful. But one moment crystallized it all: I was a kid, visiting the studio of the great abstract artist Manuel Felguérez with my father, who was an architect. The moment we stepped in, the smell hit me—oil paint, linseed, raw canvas. It wasn’t just a studio; it was an entire universe. That scent didn’t just linger—it embedded itself. I knew instantly: this was home.

Art isn’t just what I do—it’s my bloodstream. Every curiosity, every anxiety, every exploration flows through it. The books I write, the films I make, the sculptures and installations—they’re all part of the same process. One continuous thread. One restless, expansive search.

What role does your studio and environment play in your creative process? I walk, I wander—I try to slip into the zone. To disconnect from the constant noise of the world. My work is built on memory, on scent, on private rituals I’ve developed over time to access the deeper layers—the ones that live beneath language. The ideas that circle in my head aren't linear; they come in waves, fragments, pulses.

I often feel like a custodian in an ancient library, flashlight in hand, checking on the fragile machinery of thought. The work defines the process. The act of making sets my rhythm, shapes my thinking. I don’t impose ideas—I respond to them. It’s the same in film. Most of what I create arrives uninvited. I just try to be present enough to catch it.

I believe deeply in randomness, not as chaos, but as a kind of cosmic frequency. A rhythm that’s always pulsing, if we’re quiet enough to feel it. I’m endlessly inspired by the cave artists from 40,000 years ago. They worked from memory, too, using primal materials to speak across time. Their gestures still feel as urgent and contemporary as anything we’re making now.

I think we’re all like radios, tuned to different frequencies. My process is about listening—tuning in, catching what comes, and translating it with whatever materials are close. Once a piece takes shape, the frequency shifts. And then I follow the next one. Each one telling a story.

What projects are you at work on at the moment? And what themes or ideas are currently driving your work? I work in cycles—bodies of work that emerge through different materials and in different geographies. In my New York studio, I focus on drawing, painting, digital media, and writing. Lately, I’ve been exploring the memory of feelings—how emotion lingers, shifts, and fades over time. When I draw something that resembles a human or an animal, I’m not chasing realism—I’m trying to capture a sensation, a memory. A liminal state, like the moment you wake from a dream and the details begin to dissolve. That fleeting, elemental feeling is what I’m after.

In Oaxaca, I’m working on large-scale tapestries using sustainable dyes made from local minerals, flowers, and plants. I’m also experimenting with fabric, glass, and even my own line of eco-responsible mezcal. That studio is more of a mad laboratory—a space where ancestral techniques and contemporary questions collide. Everything begins with memory, then moves through material.

In Mexico City, I have a sculpture and bronze studio where I’m translating many of these ideas into three dimensions. That work ties back to what I studied at Central Saint Martins in London—sculpture as a physical extension of gesture, thought, and mark-making.

Across all of it, I return to drawing. Drawing is the root. Everything else—film, sculpture, text, mezcal—grows from that practice.

What impact do you hope your art has on viewers?

It’s not for me to define—it’s up to them to tell me.

I’ve never believed in prescriptive artwork.

What I hope is that the work transmits energy. That it helps people feel more human, more present. That it opens a small space to go deeper—to feel something they didn’t know was still alive in them.

Which artists, past or present, would you like to meet? The great cave artists 40,000 years ago.

Louise Bourgeois

Julie Mehretu (again)

Mikhail Bulgakov

Mark Twain

El Anatsui

Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz

Prospero

Joseph Beuys

Paul Klee

Cy Twombly

Tom Freidman

Do you draw inspiration from music, art, or other disciplines? Music for sure from my friends Warren Ellis & Nick Cave to Perez Prado. Many writers of them as I also write books. Filmmakers, I make films, but I'm super inspired by many amazing filmmakers like Nadine Labaki.

But also scientists and so many other worlds that I love to explore.

A great thing about living in New York is…

I love it. Coming from Mexico City, it feels almost quaint—a small island where I can hop on my city bike and be at the Met in 35 or 40 minutes. But Mexico City is still home. It’s where I grew up, and it continues to shape me. So I move between both places, each offering something essential to my work and rhythm.

Can you describe a project that challenged you creatively and really tested your emotional limits, and how you worked through it? During the pandemic, I wrote and illustrated a novel for my daughter called Monarca. It began as a personal project—I drew over a thousand butterflies. I grew up visiting the Monarch butterfly sanctuaries in Michoacán, Mexico, where millions of butterflies migrate from Canada to a few protected forests. Seeing it in person is overwhelming—like witnessing the greatest love fest on the planet. It’s one of the few places where I can say, without hesitation, that magic exists.

That book, co-written with my dear friend, filmmaker and activist Eva Aridjis, was eventually published by HarperCollins as an illustrated novel. But it didn’t stop there. Monarca became a seed that grew into larger works: installations, music, and expanded visual pieces.

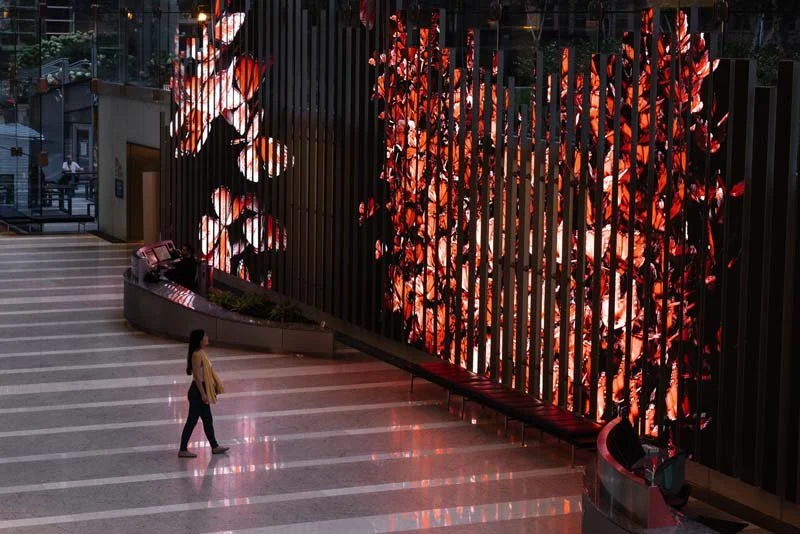

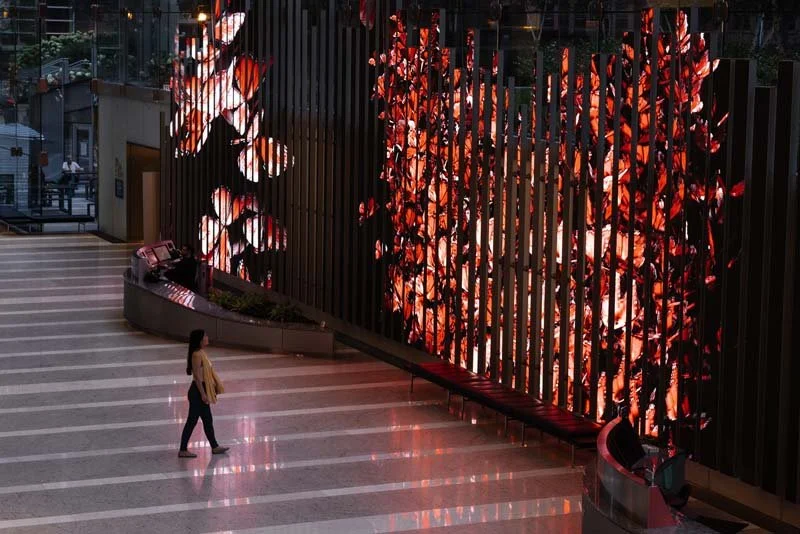

The real turning point came about a year ago, when I was invited to have a solo show at Povos Gallery in Chicago—near one of the largest digital screens in the country. It was curated by Yuge Zhou, a brilliant artist herself, who invited me to participate. I’ve always had a complicated relationship with digital art, so this felt like a challenge I had to take seriously: could I create something large-scale, digital, and still retain the tactility and emotional resonance I value in physical work?

With the help of my brilliant collaborator Mat Buinooge, we created a piece over the course of a year—thousands of hand-painted elements that we translated into a digital mural. My goal was to bring something of the spirit of Mexican Muralism into the digital realm, to see if I could make something that felt honest, textured, and grounded—despite the medium.

The question I kept asking was: Can a digital mural feel tactile, human, and good—at least by my own standards? And after all that work, I believe we pulled it off.

Tell us about important teachers and mentors in your life. There have been so many influences. First and foremost, my mother, Andrea Valeria—a brilliant humanist, writer, and magnetic force of nature. Anyone who met her was drawn in by her presence. Her home was a sculpture, her life a living artwork. She shaped the way I see the world. While studying in London on a full scholarship, I lived with Thomas Houseago. As a young artist, that experience left a lasting impact—his raw energy and fearless approach to sculpture opened up new possibilities for me.

My brother, Everardo Gout, is a phenomenal film director and one of the most focused, passionate people I know. His ability to commit with total intensity has always inspired me.

And then there are the women in my life—my wife, my daughter, and the many artists, thinkers, and dreamers I’ve crossed paths with over the years. My son, too, and so many others have shaped this layered life I’ve led—across disciplines, across cities, across forms.

Can you share a memory or reflection about the beauty and wonder of the natural world? Does being in nature inspire your art or your process? So many. My mother was an activist, and I grew up surrounded by people who championed countless sustainability and ecological initiatives throughout Mexico. I’ve chosen to focus my energy on a few distinct projects, and here are two I’m actively working on:

The Monarca Project is my long-term commitment to protecting the monarch butterfly sanctuaries in Michoacán. It spans books, films, immersive experiences, and multidisciplinary artworks—all rooted in a profound love for those forests and the miraculous migration of the butterflies. I believe art can reframe how we connect with the natural world—and that belief drives everything I do with Monarca.

3 years ago, I had the honor of dining with the late, legendary photographer Sebastião Salgado. He and his wife reforested an entire region of Brazil—an act of extraordinary vision and perseverance. That conversation never left me. I may not be able to save the entire planet, but I’ve made the Monarca sanctuaries my life’s project. And we are already undertaking meaningful action.

In Oaxaca, I’m collaborating with artist and scientist Christian Thornton, who has pioneered a process that reduces the carbon footprint of both mezcal and glass production by over 85%. Together, we’re developing sustainable artistic and manufacturing methods that push back against the celebrity-industrial complex that now surrounds mezcal and tequila. These days, it feels like everyone has their own bottle—yet few consider the environmental costs of industrial overproduction.

We’re also co-directing a film with the brilliant Indigenous filmmaker Dana Castillo. Through the film and our products, we’re sending a message: there is a better way. Celebrities wield enormous influence—and with that comes responsibility. They can be part of the solution, not just profit from the problem.

AI is changing everything - the way we see the world, creativity, art, our ideas of beauty and the way we communicate with each other and our imaginations. How do you see the future of creativity evolving alongside AI and automation?What is the importance of human art and handmade creative works over industrialized creative practices? AI—like Photoshop or Google—is ultimately just a tool. A powerful one, yes, but still a means to an end. I use it when I need to articulate something that resists conventional expression. I welcome any technology that expands creative potential. But I worry when it becomes a shortcut rather than a catalyst—when ease replaces depth.

True beauty lies in deep learning, in sustained attention, in the slow accumulation of insight. It’s in the years spent with paintings that continue to reveal themselves, in the rereading of a novel like The Master and Margarita that always yields something previously hidden. That kind of layered, evolving relationship—between art and the self—can’t be replicated by an algorithm.

Tools should support our instincts, not override them. They should awaken our curiosity, not anesthetize it.

I love making art—with my hands, my body, my senses. No machine will ever take the charcoal or clay from my fingers. Because for me, creation isn’t just about the result—it’s about the ritual, the resistance, the joy. I still ache with the scent of oil paint, with charcoal dust in my palms, with the weight of paper. That’s my true sanctuary. Making things is still my sunrise.

Exploring ideas, art and the creative process connects me to…

a primal state of being—like tuning into a hidden frequency. In those moments, I become a kind of receiver, a living radio. I catch signals that exist beyond language or logic, and I work through them—shaping, bending, translating—until something real emerges. Something tactile. A sensory experience.

At its best, it’s a kind of ecstatic transmission—not just for me, not just for my psyche, but for anyone who encounters the work. If I’ve done it right, it’s not just visual. It’s something you can feel, smell, maybe even taste. I want the work to touch people as deeply as it touches me—viscerally, emotionally, fully: a complete and total ARTGASM.