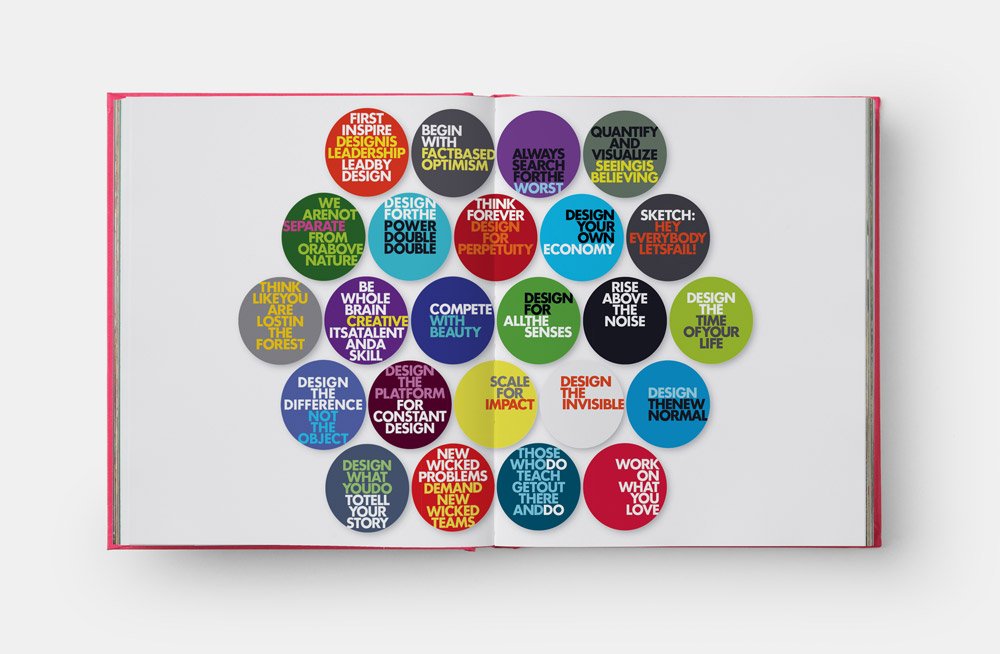

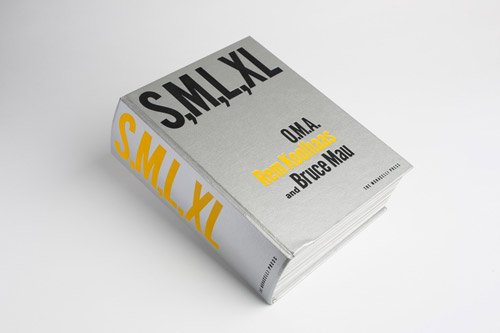

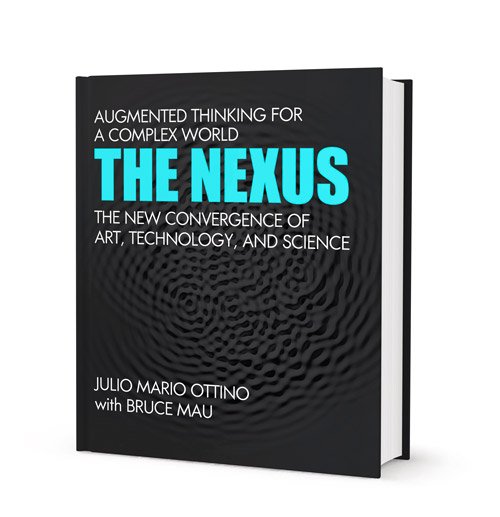

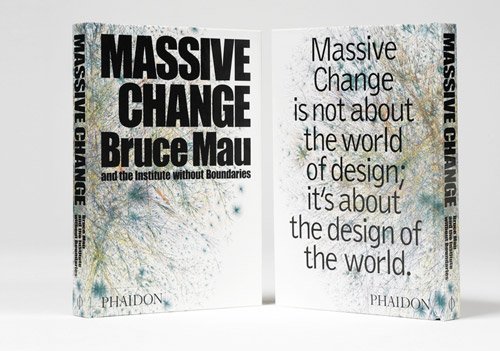

Designer, author, educator and artist Bruce Mau is a brilliantly creative optimist whose love of thorny problems led him to create a methodology for life-centered design. Across thirty years of design innovation, he’s collaborated with global brands and companies, leading organizations, heads of state, renowned artists and fellow optimists. Mau became an international figure with the publication of his landmark S,M,L,XL, designed and co-authored with Rem Koolhaas, and his most recent books are Mau MC24: Bruce Mau’s 24 Principles for Designing Massive Change in Your Life and Work and, with co-author, Julio Ottino, dean of Northwestern University’s McCormick School of Engineering, The Nexus: Augmented Thinking for a Complex World – The New Convergence of Art, Technology, and Science. Mau is co-founder and CEO of Massive Change Network, a holistic design collective based in the Chicago area.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS & ONE PLANET PODCAST

It goes back to that being lost, training yourself to be lost, and it seems like one of the great challenges, not just for a designer, but just for everyone.

BRUCE MAU

You know, that is a big, big idea. I'm very, very concerned that we are already in a time of being lost, that a lot of people feel lost, and they feel like the world has kind of moved out from under them, and that they have lost their bearings. They've lost their anchor, and they don't have what it takes to actually navigate.

And in that kind of environment, it's a very rich environment for fascism and for the worst kind of political movement, for the worst kind of political actors to take advantage of that feeling of powerlessness and fear and disconnection. Design is a methodology that is an empowering methodology within a condition of being unmoored.

So when you don't know what to do, design is a methodology of figuring out what to do. So it's a very important empowerment tool, and it's why we're doing a project that we call Massive Action, which is to really give people the tools of empowerment to give them the power to design their life because over the coming couple of decades people are going to see a level of turmoil and change that has not happened in human history. We have to change practically everything. I mean, practically everything that we do. You know, the foundation of our society is our energy system. The foundation of any culture is energy, and we have to change fundamentally our source of energy, which is going to change everything else.

So every tool that we use, every vehicle, every system, every everything we plug in or charge up or anything, everything that we do has to change. And people are going to go through a level of, turmoil and conflict and disconnection that hasn't happened before. And I really worry that it's going to be a time – and we're already seeing it - it's going to be a time where the forces of autocracy and totalitarianism and fascism will find fertile ground if we don't actually help people navigate those conditions.

You really need to think about it holistically. We've disconnected ourselves from the living world, and we have this beautiful quotation from David Orr, he's an environmentalist and teacher, and he said, “Can we imagine education that doesn't dominate nature?“ And I think, the jury is out. We have to actually reconceive it. We have to think about a living world that we're part of. And what I found so interesting working in Sudbury at this architecture school that I'm part of is - the McEwen school is a collaboration between French, English, and Indigenous leaders - and so I've been on the board now for several years. I've been going up there and working with these folks. And I discovered that the Indigenous folks have a different cosmology. They don't put humans at the center. They put life at the center, and one of the guys said, “We think that we are related to the rocks and the grasses,“ which is actually what E.O. Wilson said, “Rock is slow life, and life is fast rock.“ So here you have the greatest life scientist in the last half-century saying the same thing as the Indigenous cosmologist. So spiritual cosmology and science are coming to the same place. When I realized that I thought–Wow, this is just an incredible, incredible situation that you have science and spirituality coming to the same place.

*

When we were working in Panama with E.O. Wilson on the Panama Museum of Biodiversity for the world's first museum of biodiversity, we went into the jungle with E.O. Wilson, and he explained that there's only one thing on the planet and that's life. And life has an experiment going in form. We are one of those forms, and over 99% of all the experiments have gone extinct. So less than 1% of all the forms that ever existed now exist. And we're living through another one of the mass extinctions. Many of those are going to go extinct. We may be one of those, and life goes on. Life will go on. And he said, “Rock is slow. Life and life is fast rock.”That you are rock animated with electricity, and when we turn that electricity off, you go back to rock. You return to the Earth. And that's all it is.

There's an endless cycle, and the sooner that we get that concept into our way of thinking, into our cosmology, into our way of understanding the universe, into our way of working, the sooner that we'll start to actually do things that have a plausible future. The way we are working now, we're just drawing down our future. We're drawing down the resources of the Earth."

Images Courtesy of Massive Change Network

I don't start knowing what to do. I start trying to understand what the opportunity is. It was actually my friend Marc Mathieu, who is the head of global brand at Coca-Cola, who - after we built the global sustainability platform for Coca-Cola, after we finished the work, Marc said, “You know, Bruce, the best thing you did, you didn't charge me for it. You didn't tell me you were going to do it. I don't know if you even know that you did it.” And I said, “Please, please tell me.” And he called it “branding the opportunity.” And I said, “What do you mean by that?” And he said, “Well, you were able to articulate the opportunity in a way that inspired everyone on the team to move in the same direction. Before you arrived, we had 150 people pointing in 150 directions, and the way that you were able to see the problem and articulate the opportunity – What would happen if we accomplished it, the impact that we could have in the world, it inspired everyone to work towards it.”

That's an important thing to do in your work is to actually articulate the opportunity and not only the problem. To say, look, here's what happens if we do this? If we do this, and we succeed, how is the world different? I like to say that when you lock in, you also lock out. So the moment that you lock in on what you're going to do, you're also locking out everything else. Right? So when you define what you're going to work on, you're defining the scope of the opportunity.

*

Cities are certainly a great place to start because the way that we do them - you can see it if you go up in an airplane and look down - you can see that they're built against nature. You can see it in the color of the city. It's interesting. We reflect it in our maps. Cities are gray, and the rest of the world is green. We build them against the natural world, and the way that we do it - concrete - is one of the worst environmental materials we could use, and we have no intention, at the moment, of changing that.

And we're going to add roughly two more billion people, almost all of whom will live in cities. The scale of that problem is absolutely staggering, and we intend to put them in buildings. No one I've found is willing to say, No, actually you've got to stay outside. No, we're going to put them in buildings. And we're going to build about half the world again to accommodate it. So all of that has to change, and the good news is that there's huge effort being made, huge innovation projects all over the world.

*

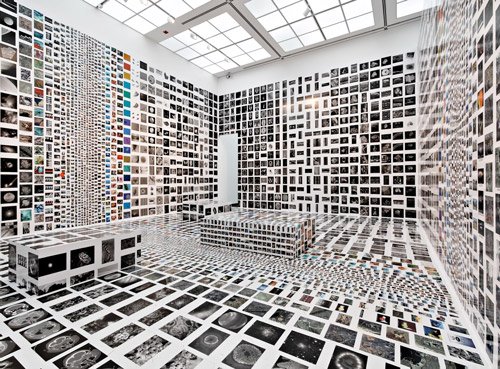

When I discovered what happens when you put images and words together, I just fell in love with it. Something else happens. You know, it's not images, and it's not words, it's something else. And that's something else is design. And I just was completely seduced by it as soon as I started doing it. And I'm still doing it.

I'm a big fan of Marshall McLuhan, and McLuhan really talked and wrote about typography as a medium and how it shapes the mind. And how it shapes what we experience and shapes how we see things. And so I think of typography as a window that you look through. So you look through the typography at the content. You don't see the shape of the window, but the shape of the window determines what you see. So you're not looking at the window. You're looking through the window, but it's coloring, it's shaping what you see, but most people are not conscious of it. They don't realize - this was McLuhan's great thesis - that they don't realize that it's working you over, right? That's why he called it "the medium is the massage." He didn't actually say “the medium is the message."

THE CREATIVE PROCESS & ONE PLANET PODCAST

What would you like young people to know, preserve and remember?

MAU

I would like them to know that, you know, in my own case, that I did as much as I possibly could have. I can't say that say the same for my generation. We made a lot of mistakes, but in a way more importantly, I would like them to know just how powerful they are, that they have the power to shape the world. At some point, I realized that the world is produced. The world is designed and produced, and since we designed and produced it, we can redesign it. And you can play a part in designing it. You can play a part in that production. It doesn't have to happen to you. And I think, for too many people, too much power and too much control is concentrated in too few hands. People need to have the power to control and design their own life.

This interview was conducted by Mia Funk and Bruce Piasecki. Associate Interviews Producer on this podcast was Amy Highsmith. Digital Media Coordinator was Doug Evans.