On the urgent need to reclaim our political voices, the forces that silence dissent, and how art and poetry are crucial tools for survival

“There is a dispute about what the American Dream is or how it would play out in different circumstances. The American dream has essentially been narrowed into a white Christian nationalist notion of things so that everything that falls outside what they imagine that to be is not only undesirable, but should be the subject of extermination, deportation, and detention. I am heartened by the fact that more of our 'better angels' are emerging with a more capacious and expansive notion of what the American dream could be.”

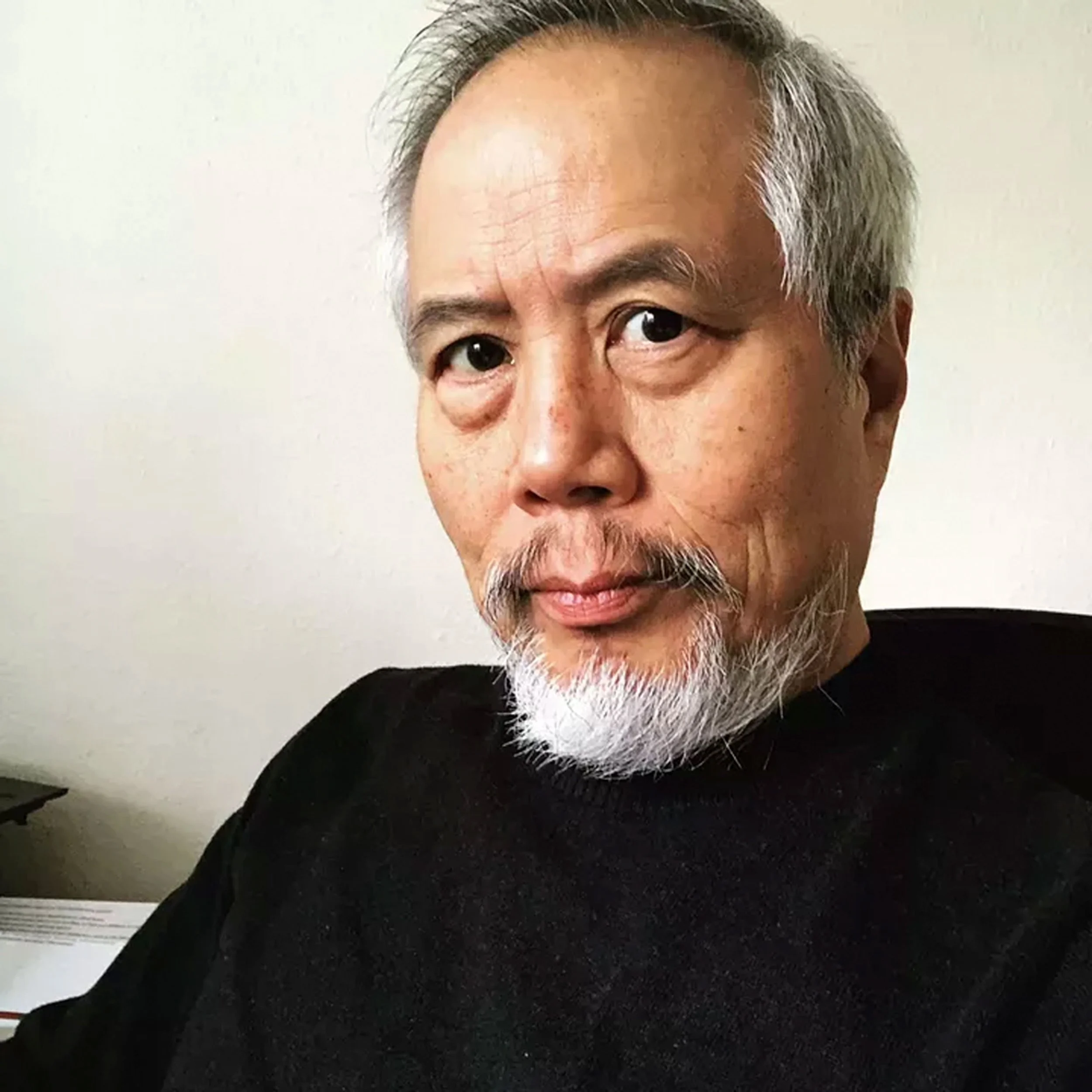

Our guest today is an activist scholar who believes the classroom is inseparable from the public square. David Palumbo-Liu is the Louise Hewlett Nixon Professor of Comparative Literature at Stanford University and a founding faculty member of Stanford’s Program in Comparative Studies in Race and Ethnicity. But his work has long reached beyond the academy. Through his book, Speaking Out of Place: Getting Our Political Voices Back, and his podcast of the same name, he insists that the great global crises of our time—from escalating wars and democratic failures to environmental collapse—are fundamentally crises of value and voice.

His recent work has put him on the front lines of campus activism, challenging institutions, resigning his membership from the MLA, a move that highlights the ethical cost of speaking truth to power. We’ll talk about what he calls the "carceral logic" of the modern university, why art and poetry are crucial tools for survival in times of war, and what he tells his students about preparing for a future defined by uncertainty. His perspective is rooted in literature, but his urgency is all about the world we live in now. We will discuss the forces that silence dissent, the "imperial logic" of AI, and what it means to be a moral, active citizen when the systems we rely on are failing.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

What is the American dream to you today? Because there is a real underside to this.

DAVID PALUMBO-LIU

Yes, because there is a dispute about what that dream is or how it would play out in different circumstances. Of course, everyone in the United States and probably beyond—but most especially those of us who have to live under the Trump regime—is constantly being shocked day after day.

As I mentioned a moment ago regarding American institutions, Trump has effectively destroyed nearly every one of them. Fortunately, at a certain level, the courts are holding up, and the people are finally standing up. I think that has been one sign of great hope, even for the MAGA base, which is diminishing.

Unfortunately, the American dream has essentially been narrowed into a white Christian nationalist notion of things. Everything that falls outside what they imagine that to be is not only undesirable but should be the subject of extermination, deportation, detention, and massive investigations. Former directors of the CIA and FBI—anyone who is perceived to disagree with Trump—is put under immediate investigation because those things must be eradicated.

On the other side, as explored in my interview with Ellen Schrecker—a longstanding American historian of McCarthyism—people are standing up. Ellen points out that, unlike during the McCarthy era, people are resisting this time around. It has been incredibly heartening to me. There was a recent story about suburban grandmothers in Chicago standing up to ICE to prevent deportation. I think it is tapping into the best and the worst of us. I am heartened by the fact that more of our "better angels" are emerging with a more capacious and expansive notion of what the American dream could be.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

I always wonder, when you are an activist, how do you measure success when can be such a long haul?

PALUMBO-LIU

I ask that question in nearly every episode. When I spoke with Ahdaf Soueif, she quoted John Berger’s notion of "undefeated despair." Similarly, Robin D.G. Kelley has a line regarding "success without victory."

There are many variations of this idea: small successes that do not necessarily amount to a total victory but, day by day, leave possibilities open. These are small victories, like having someone wave to you in a neighborhood that would not usually recognize you. All those things keep possibilities open. Berger’s expression is so meaningful because we must acknowledge our despair. It would be foolish for us to "tough it out" and imagine it does not count. Of course, it counts, but it is a despair that then feeds into an even more profound commitment precisely because you recognize it. That is where the "undefeated" part comes in. You recommit. It is not defeated; it is still alive but cognizant of the enormity of the task.

Again, a theme we have discussed today is the sense of breaking isolation, even if it is only momentary. It shows up in almost banal ways. When I am on my walk in the preserve and I am systematic about saying hello to people, seeing the smile on their faces when they reciprocate is vital. Even that sign of recognition is important; otherwise, we are hunched over our phones or lost in our darkness, feeling like there is nothing we can do.

In the United States, I have never seen such a mass movement. The closest thing to it was the anti-war movement. This galvanizes people. This is where someone like Marjorie Taylor Greene comes in. It involves people from both sides of the aisle, so to speak. As you say, she is a politician, so you never know what calculation she is making. However, what lies behind it—regardless of her actual motive—is a recognition that the old two-party system is not working.

I do not know if you have watched the historian Heather Cox Richardson, who has become quite popular. I do not agree with her all the time, but I think she has exactly the right sensibilities. She constantly compares this era to the mid-19th century, when the robber barons held a notion that only the entitled elites were capable of running a country because everyone else was perceived as "stupid." When asked if we should have a third party, she argued that in the United States, the two-party system is here to stay, yet parties can change.

I think the Democrats and maybe even the Republicans at some later stage are recognizing that people care about basic things. They care about having food on the table and healthcare. This cuts across issues of identity or sexuality. Everyone deserves basic human rights: a right to an education, healthcare, retirement, and a voice in how the state runs. Reasonable disagreement is fine, but I have never seen such sustained polarization, to the point where our president tears down half the White House, and people say it is fine. People have finally reached a point of saying, "No, it is not fine." I think these next four years will be very interesting. It will get worse before it gets better, which is why we need to be undefeated in our despair.

I was interested to listen to one of your recent guests, Eunsong Kim, who detailed how the Frick Collection and other elite institutions were founded upon erasing the labor of union-busting robber barons. I had not really reflected on that. You talk about beauty and the importance of art. The Frick is a beautiful collection—I interviewed their director—and I thought of it as a place of solace. But it is sobering to think it is built on this kind of property.

PALUMBO-LIU

What she brings out is very interesting. I use part of that to talk about immigrants "jumping the tracks," so to speak. This goes back to the episode I did with Puja Baia Batia, who was in Springfield, Ohio, during the period of the "eating the pets" rhetoric.

Dehumanization works when you take away the human contributions people make. It erases the fact that we are so dependent on migrant labor. When you substitute the narrative that they are all criminals stealing things, rather than the reality that they are giving us things, it is truly devastating.

The robber barons were actually robbers. Woody Guthrie, the famous American folk singer, has a line: "Some will rob you with a six-gun, and some with a fountain pen." This is what happened during the Dust Bowl in the 1930s, when bankers robbed farmers by forcing them into huge loans for the tractors and combines they needed to be competitive.

Of course, here I am at Stanford University, founded by one of the great robber barons, Leland Stanford, who famously hired a number of ex-Civil War soldiers to hunt Indians. Malcolm Harris, in his book on Palo Alto, lays this out forcefully. We are in another Gilded Age. There is no doubt about it when you have individuals like Peter Thiel and Sam Altman deciding that democracy is a dispensable artifact, and that brilliant people like themselves should determine what is good for the entire planet. That is a level of "robber barrenness" beyond imagination. People are finally getting disgusted when they see the degradation of life for most people and the cost we are bearing for this robbery.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

As you reflect on your life as a teacher and activist, what would you like young people to know, preserve, and remember?

PALUMBO-LIU

I will borrow from a recent guest, Nilo Tabrizy, who works for the Washington Post in visual forensics. She co-authored a book about the Iran rebellion, Woman, Life, Freedom. As someone in visual forensics, she had to look through thousands of photos of tortured bodies to substantiate a story. I asked her how she does it. She mentioned that her therapist told her she must "turn off" and have dedicated time to do something else.

Self-care is vital. It should not be a mere 15 minutes of something minimal. One thing I say to myself all the time is that the world can get along without you. That is not to say I do not make a contribution, but the natural world is amazingly resilient and the human world has others to carry on. We are all interdependent. As long as you are doing what you can while you are engaged, you also need the arts, music, and silence. These things are for your good and the good of the community. It is not a luxury, and it is not backing away.

I will tell a story regarding the first Trump administration and the Muslim Ban. There were spontaneous demonstrations at major airports. I remember going to the San Francisco International Airport (SFO) and seeing masses of people. I even ran into my dean there. I had another commitment and noticed people were leaving, but as they left, new people would organically arrive to take their place. That serves as a metaphor: no one is a full-time activist, and everyone needs time off. As long as we share a spirit of common values, there will always be someone else there to stand in.