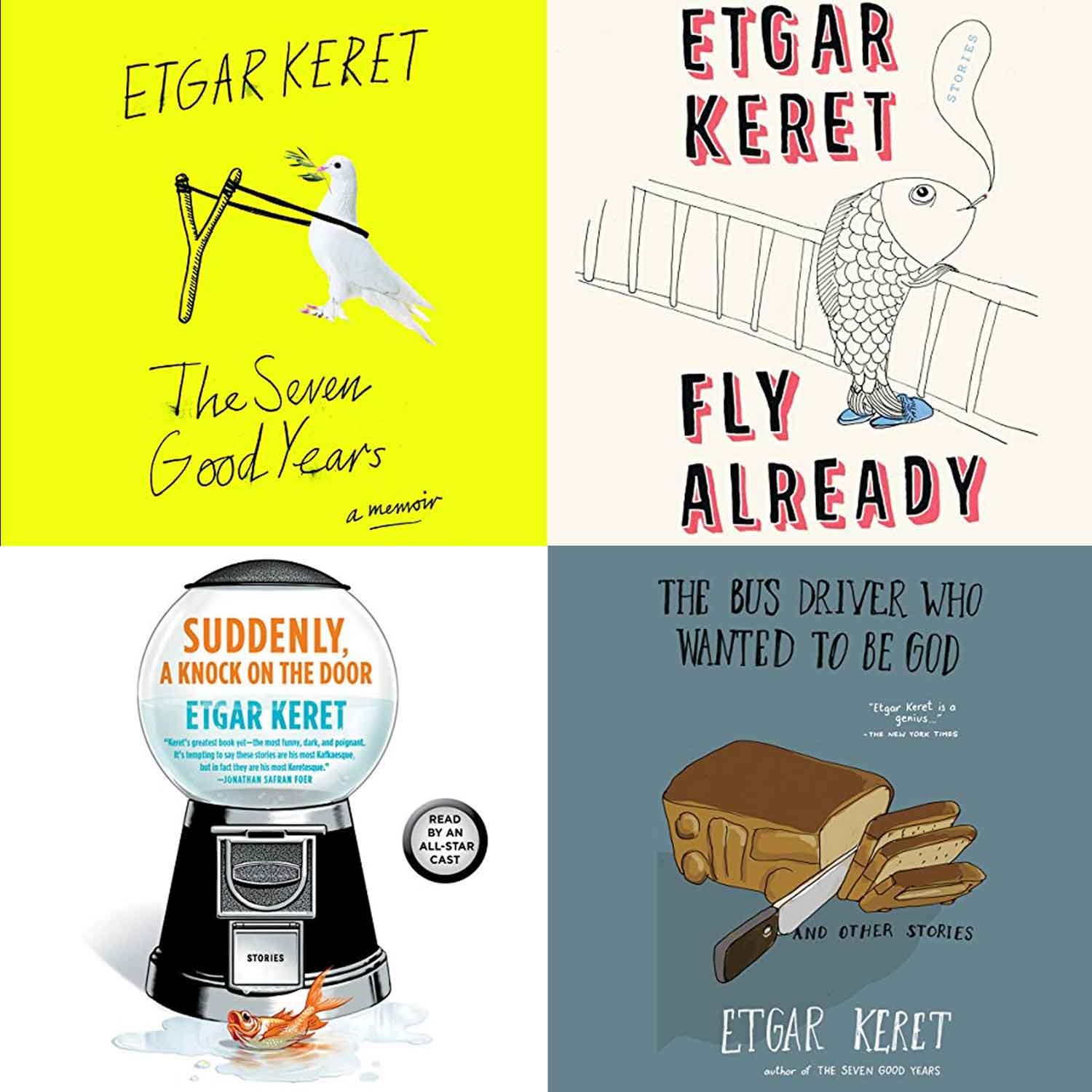

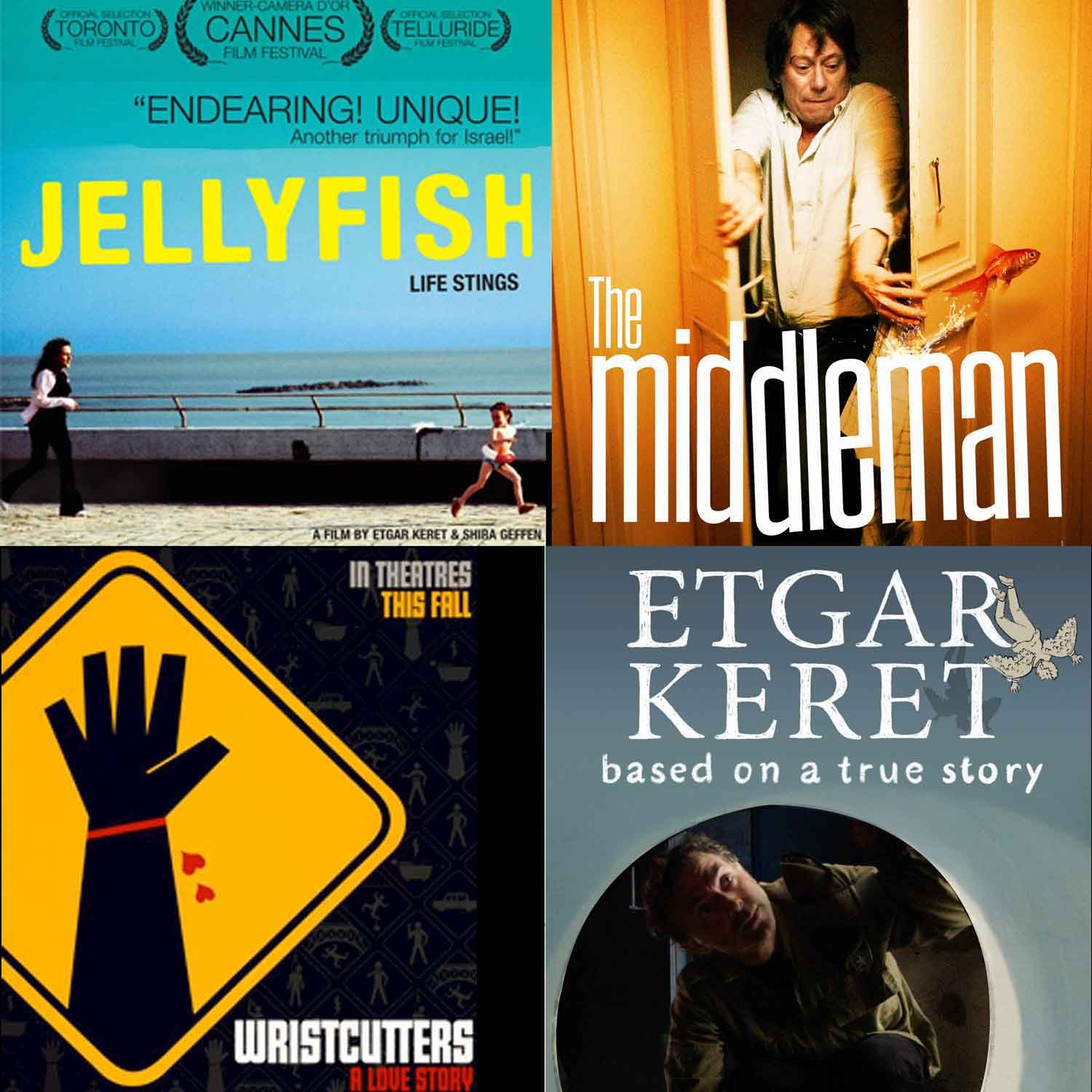

Author, Screenwriter, and Director Etgar Keret is a recipient of the French Chevalier des Arts et des Lettres, the Charles Bronfman Prize, and the Caméra d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival for Jellyfish, which he directed with his wife Shira Geffen. Most recently, they created the TV mini series The Middleman (L’Agent Immobilier) starring Mathieu Amalric. His books include the short story collections Fly Already, Suddenly a Knock on the Door, and his memoir The Seven Good Years. Etgar’s work has been translated into forty-five languages and has appeared in The New Yorker, The Paris Review, The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, Wired, and This American Life.

A frequent collaborator with visual and performing artists, an exhibition inspired by his mother called Inside Out is currently showing at the Jewish Museum in Berlin until February 5th, 2023.

Find Etgar on Substack

ETGAR KERET

For me, there is something about art, it's not a monologue, it's a dialogue. Some people, it doesn't matter who they speak to, they will speak in the same way they would speak to a five-year-old or to an intellectual or to somebody who doesn't speak the language very well. They would speak the same way and they don't care because this is what they have to say, but I think that the natural thing in the dialogue is really to look into the eyes of the person you speak to and see when he understands or when she doesn't understand or when she's moved or when he's angry. And basically out of that, kind of create your own language. And I think the same way that people are excited about learning and speaking different languages - because I think each language has different merits and different aspects.

So I basically speak Hebrew and English. Many things in the world are easier for me to understand through English and not through Hebrew, so this idea, this kind of learning this new language allows me some kind of versatility and understanding the world better. So I think that having a dialogue with specific and different kinds of audiences does the same. When I started publishing and my books, started becoming successful, the first thing I did was I wrote a children's book because I thought, In life, I like speaking to adults, but I also like speaking to children.

Because my mom grew up in a period where they were excited about Nazi ideology and my mom knew this wasn't a good thing. So this idea of making up your own story instead of taking other people's stories was something that was very important. When I was a child, my mother didn't allow children's books in our home because she insisted on making up the stories for us. For her, basically, it was like the idea of reading us classics from a book was like ordering a pizza instead of cooking dinner. It meant that she didn't care about us. And she felt that because her parents told her bedtime stories in the ghetto where they had no access to books. And she saw how those people who were broken and angry and hurting could still find in their imaginations a brand new story that they made for somebody that they loved. So for her, it was this kind of generosity and something that could not be compared to, for example, buying Alice in Wonderland and reading it to somebody. You had to give more than that.

You don't hire somebody who will make love to your lover for you, and then you say, “I love you so much, I hired this really good guy or good girl that will make love to you instead of me.” So this idea of being there and being authentic and giving yourself was really, really important to her.

And I think that from a young age I've kind of learned that there are good stories, great stories, but none of them is your story. And that you have to kind of make up your own story, not feel just good enough kind of picking up one. And it doesn't matter if it's about Flat Earths or some conspiracy or wanting to clear the world of plastic or going vegan - which I am, vegan. So just this idea of joining some kind of boy scouts or wearing some kind of uniform or supporting some sports club and saying, Okay, now I don't have to think, I'm the New York Knicks fan! So if they win, I'm happy. If they lose, then I'm sad. I think that there is something, both with my mother and my father, being Holocaust survivors, being orphaned, basically, they had to seek the narrative. They didn't inherit one.

It's not like my parents always said, You do like this, you know, and then you can either do what your parents said or rebel against them. It's this idea of What the hell do I do? And I'm looking outside and inside to find my narrative, to find my ethics, to find my values.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

I think in your work, as you said, obviously that's a collaboration when you have a translation, so the translator is putting it in the idiom and the tone. Also, in your other work in film, dance, or your television show The Middlemann (L’Agent Immobilier), this had a very French sensibility. You seem to orientate your work around the local culture. You adapt, and it just felt completely of a piece, with of course wonderful acting by Mathieu Amalric, Eddy Mitchell, and others. So it was very beautifully done, and it got right into, I feel, our sensibility.

KERET

When I do a video dance for a Japanese audience or a sci-fi comedy for a French audience then I do try to think about if I want to shock the audience at a certain moment. I think that the same things that would shock a French person would not necessarily shock an Israeli or a Japanese person, you know? I think that what's funny is that for a lot of people, the fact that The Middleman (L'Agent Immobilier) is very extreme, but in Israel when they watched it, they never thought it was extreme. They said it was very funny, but because the Israeli reality is much more extreme, so the idea of people shouting at each other or breaking a wall or punching each other or doing weird stuff, the French said, “Oh, it's over the top.” In Israel, they felt that it was just like the way things are. So it's very, very interesting.

Some people, it doesn't matter who they speak to, they will speak in the same way they would speak to a five-year-old or to an intellectual or to somebody who doesn't speak the language very well. They would speak the same way and they don't care because this is what they have to say, but I think that the natural thing in the dialogue is really to look into the eyes of the person you speak to and see when he understands or when she doesn't understand or when she's moved or when he's angry. And basically out of that, kind of create your own language. And I think the same way that people are excited about learning and speaking different languages - because I think each language has different merits and different aspects.

*

If I try to think about my mother's story it's really this idea that you don't have a complete picture, but it's broken to pieces. And you can look at each of them and try to imagine the pieces or collect them, but there is something that is fragmented by nature.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

In fact, insisting on a whole picture is probably the larger illusion or a larger lie because, in reality, there is no complete picture. I think to have that you would have to be God, right?

KERET

I think that there are many complete pictures, but in a sense, they are all kind of redacted. And the truth is that it's strange, but I feel that, let's say, if there's a collective narrative that you totally identify with, then one should go with it. It doesn't matter if it's the Catholic Church or Antifa or the Klu Klux Klan. If people say something, they say, Oh my God, yes! They got it! They cracked it. Yay! Give me a torch. Now I got it. It's good enough.

But I think that, at least the experience that I've had, many times it's that I'm too passive. And there are all kinds of narratives passing by, and I hitchhike, kind of sitting on a narrative without really judging and thinking, to say, Oh, it's nice. Oh, people say it's good. You know? And from my mother, I learned to be very, very critical of all those narratives. Because the fact that many people say something and are excited about it, doesn't mean anything.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

I think this nurturing, comforting thing that you provide in your art…you’ve mentioned opening doorways to other lands, from your very first story “Pipes” or later stories like “Lieland” or “Unzipping”. You create these other worlds where your fictions, your lies in “Lieland” come to life, and they're magical. That’s something that recurs in your fiction?

KERET

I really feel that if there is something about art that I seek - I think people use art for many things - it's really some kind of a belief that we can transcend. I mean, if I try to kind of see it as some kind of a substitute for a religion. You know, religion tells us that there's something out there. There's somebody watching us, somebody doing something. And I think that for me, many times good art says there is something beyond our understanding that exists, and there is a way to get a step closer to it. Maybe not to unveil it, but we can get there.

And I'm saying that in The Middleman (L'Agent Immobilier), it has this aspect that the guy in it is not nice in any way. There is nothing nice about him, but you see in the series that whatever the starting point, he can get better. So if he's obnoxious, he can become less obnoxious. If he's unloyal, he can become a little bit more loyal. This idea that we can move, it's really, really important.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

Tell me, what was the last conversation you had with your mother?

KERET

Well, the last time we talked, she was already in dementia. So I think that the last time we talked, I held her hand. She said I love you. And I said, “You know who I am?” And she said, “Yes, of course, don't be silly. You're my father.” I think this was the last conversation we had, or something like that.

There is something about both my parents, but I think especially my mother, it's as if the horrible circumstances that they lived through being Jews in the Holocaust, my mother losing her entire family - it was horrible and traumatic, but it was almost like a very extreme human experiment. And it created something. It's like many times when you put somebody in extreme situations, and most of the time he will crush or she will crush, but sometimes, a superhero will be born. And there is something about my parents, when I came to work on the exhibition about my mother Inside Out, I realized there is something about her that was so unique that it could not have been achieved in normal times. Because the thing that happened with my mother was that, when the war started, she was five years old. When the war ended, she was 11 years old. By the time she was about 10, all the people that she had known before the war had died. Her parents, her brother, her grandfather, her friends.

So I think that there was something about my mother that she was a true rebel and an anarchist, not by choice, but by education. Because the fact that she grew up in a place in which you could not trust anyone or you could not trust the narratives in which basically the grownups that she met were not like my parents - who would help me navigate life - but they were like a kind of evil orphanage managers who would steal her food or who would try to molest her or do all those horrible things. So in that sense, she kind of relied on herself for a narrative...So it doesn't really matter so much what's out there, but what matters is how you experience it.

*

I asked my father as a child, “What was the point in imagining this world? And he said, “Everything that you can imagine can potentially exist. So whenever I was hiding in a hole in the ground, and whenever I could imagine something new, I would make the space in which I live bigger and bigger and wider, and make it to this kind of infinite plane by kind of unfolding my imagination.” And I think that it's always kind of good to remind ourselves that we have an option. We're active. We can act.

I think that there is something about this age that we live in, that it's an age, I think, that everybody feels trapped. Everybody feels wronged. Everybody feels that there is no responsible adult up there. But the idea is what do you do with it? And I feel that it's all about maybe creating some kind of individual sphere, and from this individual sphere trying to connect with others instead of kind of ganging into these posts, which you like or dislike, saying that you hate this guy or like this guy. Kind of avoiding this kind of binaric reduction of yourself, just so you feel you belong to a big group, you know? And I think just like the moment I talked about my mother seeing her history as a pearl necklace, I think that the moment that we see humanity as a pearl necklace and not some kind of equation in which everybody has to give you the same results, then there will be some kind of a breathing option to any person who tries to feel better.

And again, I'm not saying that all my life I felt this way. When I was younger, I think I wanted to change the world. Now I admit, I mostly want to survive it. And I think that there is something looming from above. Let's say when I started writing in the late eighties, early nineties when I was a teenager. You know, everything, the world kind of gave you this promise that things are going to get better, that things are going to get solved. Fukuyama wrote this book about The End of History. No more wars! We're going to solve all our problems! And I think that in these kinds of times, this idea of saying I want to put my things center stage because everybody would listen to it - kind of feels like not only a young man's inspiration but also something that had to do with the zeitgeist.

But right now, I really, really feel it's time for each of us to our boroughs, and not necessarily seek the default town square, CNN, Fox News, you are feeding Facebook - all those kind of things that make you feel less alone but for the price of kind of reducing yourself to something that is very, very binaric in nature.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

You were saying that answering questions is a kind of therapy. Is therapy actually good for your writing process?

KERET

Actually, I have friends who have psychologists, so it's not as if I'm against this vocation. It's just maybe because of my biography, I had to go for Plan B. And I wrote my first story Pipes about two or three weeks after my friend died. So, I guess that this idea that I passed the trauma, and I can't go to a psychologist or psychotherapist kind of made me look for Plan B, and it kind of made me a writer.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

Yes, that goes into that idea of happiness or wanting the absence of pain. But I think that if we didn't have any, then you wonder if you were really alive. That's how we get to know ourselves and each other.

KERET

I think that one of the most powerful sentences I've read was in Faulker's The Wild Palms where the protagonist says that “Between grief and nothing I will take grief.” And again, there is some kind of hubris about it because nobody said that life is a buffet and you can choose what you want, you know? But I think there is something in this statement that between void and suffering, I'd rather be suffering. So I feel human. I feel my emotion, and I feel my life than not feel anything. This is something that I can totally identify with.

Main photo credit: Lielle Sand

This interview was conducted by Mia Funk with the participation of collaborating universities and students. Associate Interviews Producer on this episode was Jamie Lammers. Digital Media Coordinators are Jacob A. Preisler and Megan Hegenbarth.

Mia Funk is an artist, interviewer and founder of The Creative Process & One Planet Podcast (Conversations about Climate Change & Environmental Solutions).