By Henie Zhang

When I was young there was a night light in my room that would make just enough light so that, when I lay in my bed, I would see things on the ceiling. Everyone told me there was nothing there. But I knew different. Not so long ago, I made a dark space piece in Costa Mesa, where the police were sent to investigate because two people reported that it contained obscene material. When the police arrived, they found a projector with a tiny, 25-watt red bulb in a little black box with a hole punched in it. The rheostat for the light was turned down so low that you couldn't begin seeing anything unless you were exposed to it for fifteen minutes. There was no image.

—James Turrell, 1990 interview with Parkett Art

Images vanish in flight. The son of an aeronautical engineer, Turrell obtained his pilot’s license at age 16 and became a student of weather. “The things that interest me the most are some of the choices that are most difficult for a pilot,” he said in his 1990 interview with Parkett. He gave the example of “lost horizons,” a situation in which pilots lose their sense of the natural horizon and their position relative to it, such as in white-out snowstorm conditions. “It's this vulnerable area for life that I find intriguing,” Turrell said, “not because of the danger, but because of this sense of knowing where the eyes are adequate and where they are not.” At the limits of vision, light desublimates from perceptual data into a weighted presence in the world. In the middle of a tule fog, a thick ground fog specific to California, Turrell once saw the rising sun turn the entire sky red, then orange, then yellow. It was a completely otherworldly and nearly touchable landscape. The world-making qualities of light became central to his installations, which make light itself feelable temperature and extension in space and not only as an illumination of an object: “This materialization of light residing in space, not on the wall,” Turrell remarked, “plumbs the space like the space I fly in.”

To plumb what is normally unplumbable requires touch and vision to be re-formed. For example, Turrell’s Ganzfeld series (1976—) creates the experience of a totally uniform and unstructured visual field in which the viewer loses all perception of depth and shape. The Ganzfeld piece Perfectly Clear (1991) consists of a 10-15 minute experience during which a bath of changing color fills the room, punctuated by periodic bursts of strobing light. As the light changes, the boundaries of the space disappear into pure color as if being shrouded by mist. Pleiades (1983) arranges, with a similar immersive strategy, transitions between perceptual states. At first, the viewer walks into a room that appears to be completely dark. After a while, they begin to see flashes and pinpricks of light as a result of random nerve firing due to sensory deprivation. Gradually, as their eyes adjust fully to the darkness, they begin to perceive the very dim light source that has been in the room, sitting at the threshold of their visual perception, all along.

James Turrell, Perfectly Clear, 1991. Gift of Jennifer Turrell. © James Turrell, Photo by Florian Holzherr. Courtesy of MASS MoCA.

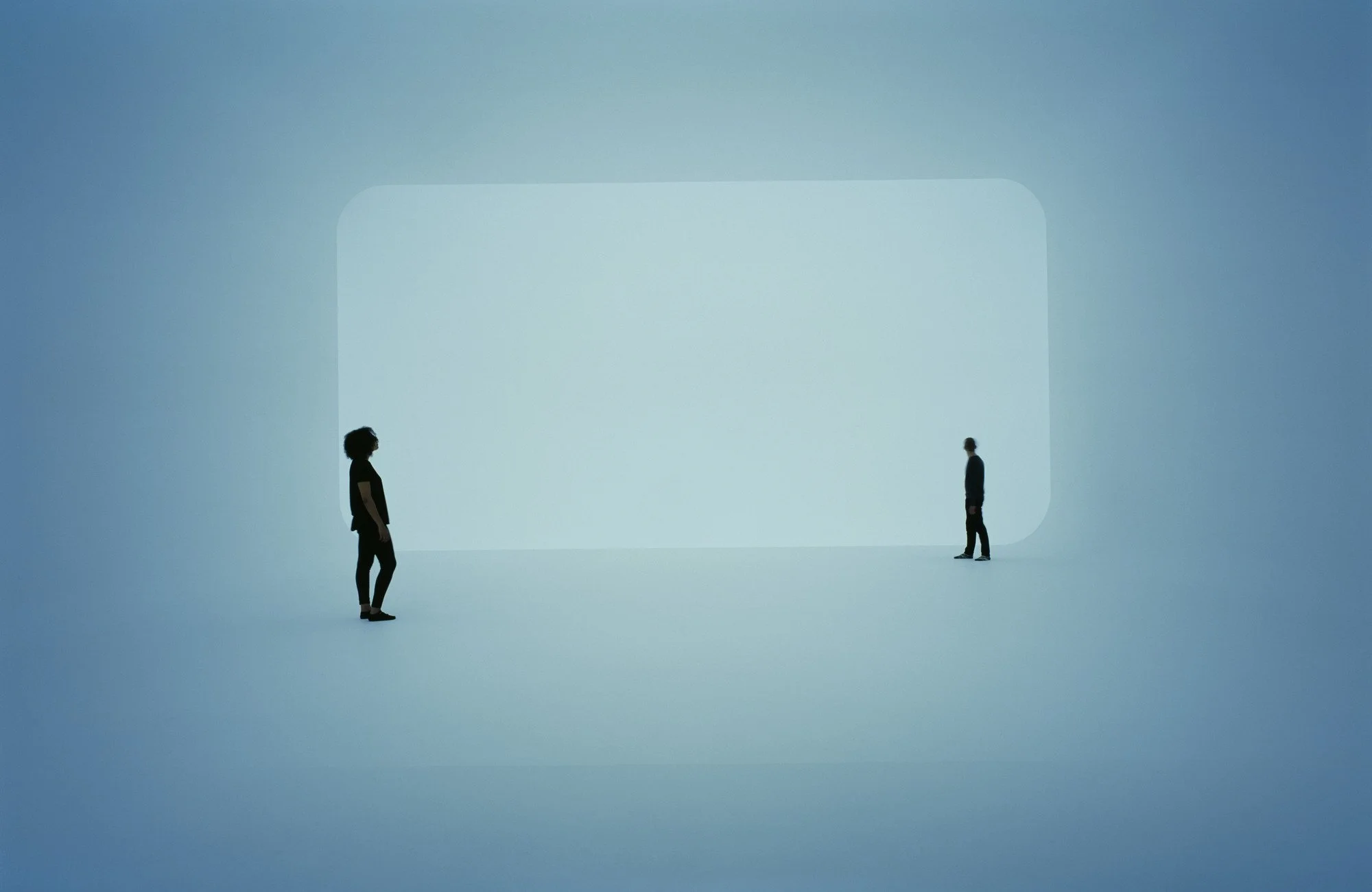

James Turrell, All Clear, 2024. Installation View at Gagosian Le Bourget, Paris. © James Turrell, Photo by Thomas Lannes. Courtesy of Gagosian Gallery.

In Turrell’s installations, such hidden presences conjured through perceptual misfires mark out the stages of a light trajectory in both space and time, one that binds the body to the space that plumbs it. In City of Arhirit (1976), another Ganzfeld installation, physical crossings become inseparable from the crossing of one’s own perceptual bounds. The installation consists of four chambers that the visitors walk through sequentially. Each chamber has a large rectangular window fitted with a translucent fabric screen to tint and even out the intensity of the sunlight entering the room. Depending on the time of year and the weather, the light reflects off of differently colored surfaces in the environment outside—the lawn, a brick wall—and shifts the color of the room in subtle directions.

James Turrell, City of Arhirit, 1976. Installation View at the James Turrell Museum, Colomé, Argentina. © James Turrell, Photo by Florian Holzherr. Courtesy of Independent Collectors.

As the viewers enter each room, they briefly experience the color of the room as intensified by the afterimage they retained of the previous room. Then the afterimage fades, and the fullness of the light in the present room whelms their perceptual field once more. As such, the visitor’s arrival into each room is announced by a physical boundary as well as a perceptual one, the latter of which is defined not by a division of experiences but by the disarming persistence of past ones. “We do learn in this culture not to see afterimages,” said Turrell in a conversation with Place Journal in 1983. But the fact is that arrival is always sticky. An outside impression will color an inside one. The “environment” is not a space you are optionally in but a kind of melody your perception arranges across experiences.

Turrell’s spaces heighten this awareness as well as demonstrate its reverse: our daily insensitivities to our own perceptual capacities and their influence on what we think of as the “world.” For example, the Ganzfeld installations demonstrate how light itself only becomes noticeable when it exceeds its purpose as a source of illumination. We almost don’t recognize it in its purest form. Smog, smoke, dust, blackouts—ganzfelds in their own right—force us to come up against the limit of seeing also as the limit of what is permissible to live in. In 1969, amidst the escalating air quality crisis in LA, Turrell argued that people would have a vastly different stance on ecological issues if they were attuned to the expansive possibilities of their own perception. Instead, “we’ve almost created an environment that we can’t live in anymore, as far as the spaces we live in that we use, that we inhabit, and that we work in, the air that we breathe, and the noise that we live with.” We live inured to those conditions that extinguish sight and sound, or cling to dogged solutionism that insists upon the capacity of future technologies to clear the smoke and optimize the grid—to restore our familiar ways of seeing—and insulate us in the meantime from the toxicities that have already contorted our perceptual relations to the world and to each other. But the damage is not just “out there.” It shapes and is shaped by what we think our perception can do and how capacious it can be. How we think about seeing shapes how we think we should live.

Turrell puts this thinking in the language of both artificial and, increasingly, natural light. Since the 1970s, Turrell has been working on a project that pushes our visual awareness into more ancient settings for seeing light, remote from modern cities and towns, where very fine qualities of light are available—such as spaces where “you can see your shadow from the light of Venus alone,” as he told Art21. The Roden Crater project, taking place inside an extinct volcano in the Arizona desert, is an architecture of tunnels, apertures, and stairways that perceptually link the sky and the earth. What is remarkable about the Roden Crater is that it, more than any other of Turrell’s works that utilize perceptual transitions, breaks the normative timescale of sight—the typical idea of vision as instantaneously received data—and opens it to much deeper repositories of time and light, light from outside the solar system and away from the Milky Way. It’s a kind of light that most of us don’t expect to receive. It’s a light that requires of us a certain nocturnal mind, an intuitive insomniac literacy of secret time, that has faded from what we think of as the “real” or normal spectrum of the visible.

Other than gathering and projecting vast fields of light, Turrell has also used light in more overtly geometric ways, transforming it into scaffolds, windows, and surfaces in a kind of ghost architecture. In the “Space Division” constructions (1976—), Turrell removed large rectangles from dividing walls to create apertures from the viewing space to another, adjacent space. The viewing space is then filled with light that is directed onto the walls from their hidden sources. Some of this light scatters against the walls and ends up in the partitioned space behind the aperture, distributing an uneven distribution of light between the viewing space and the partitioned space. This creates the impression of an opaque, solid-looking film covering the aperture. This material quality of light is heightened in the Wedgework series (1969—), in which the partitioning wall is reduced in width and used to cover a side wall to the left of the entrance. Fluorescent lights projected onto this wall at an oblique angle engender an immaterial plane running across the room.

James Turrell, Danaë, 1983. Installation View at the Mattress Factory, Pittsburgh. © James Turrell, Photo by the Mattress Factory.

James Turrell, Either Or, 2024. Installation View at Gagosian Le Bourget, Paris. © James Turrell, Photo by Thomas Lannes. Courtesy of Gagosian Gallery.

The effect is halfway between the impression of a real space and a deeply ordered fantasy. Call it an illusion—but what Turrell unsettles is more than what is and is not seen. As Turrell said of his own work, “I don't feel it is an illusion because what you see alludes to what in fact it really is—a space where the light is markedly different.” What Turrell asks for across his work is an entirely alternate way of seeing, of feeling out our own vision, that makes a different kind of world and a different way of being in it. Western culture tends to rehash the Enlightenment preoccupation with “shedding light” on information “in the dark,” and light in this paradigm is only the invisible, relentless tool by which to make the world knowable, visible, measurable. In Turrell’s chambers, there is no object to unveil. Light itself is astonishment. In other words, we do not need to see the unseen in order to have a relationship, an affinity, to it. We do not need to plot our place in space to be intensely in it. We come into a huger kind of vision with Turell, a contemplative attention unfettered from the surfaces and explanations to which it is normally made to bind. Here, perception is not an action you do “to” things but a frequency of experience that commutes between you and the world, and the disorientation and glitch at its limits are not impediments to feeling but an amphibious love of what surrounds. With Turrell, this love itself is knowledge.

Bridget in the Bardo

In response to James Turrell's Bridget's Bardo (2009)

By Henie Zhang

When I am Bridget

So Bridget is heavenly

I know Bridget when she is so heavenly

Huge ho-hum violet heaven

Violets in a violet lemon field

Look at your tulips, Bridget

They are as indifferent as my tulips

I am a fabulous insect

My mouth is an unhinged jewel

glut. Bridget lit it up,

violet fire. To be in Bridget I light up

inside Bridget's love. I want

Bridget's love, chippable, blown up

on my heart,

when I am, the fruit,

existing, inside of it,

wanting its colors,

to turn

To Turn

turn to catching it to shreds I wear it

in shreds I wear her, inside, when I am

/When she & I /

are in Love

together!

I am dementedly happy,

It is true

Bridget casts a small, sticky aura

When the light falls directly on Bridget Bridget dies

& I can no longer be loved by Bridget

When Bridget recounts for me her dreams about my dreams

Bridget thinks, "two objects vibrating against each other makes stickiness"

Says, "violet sullenness rushes bottom reason in gilded country"

I imagine Bridget as a nothing-colored violet

Singing about Bridget

Clapping her hands

Trying to find the point at which I become Bridget & wept there almost thinking almost becoming alive & wept there into the resplendent heaven of Bridget who looms finite & inert & true

My Dreams:

Am I walking in or out of Bridget?

Am I getting SICK by being Bridget?

Will I break up by shutting Bridget down?

If Bridget is me, what am I by breaking Bridget?

When Bridget weeps her tears are rhinestone ice

Bridget cries hot coals with her barefoot eyes

I put my pain inside Bridget's eyes

Bridget's Hair

Bridget's Feet

Sleet & Black Frost

in Bridge's false night

When Bridget wakes up what will happen to Bridget?

Bridget said

The pool looks pink so it can exist

oh Bridget

oh Bridget my ersatz rainbow

Tonight & all other nights

I drowned in your room & was buried

I died & was buried hilariously

I wanted to wake up a beautiful man

~

Note: "Violet sullenness rushes bottom reason in gilded country" is a riff on Jackson Mac Low's line "Coloring sullenness rushes bottom reason in gilded country," from his poem "Stein 100: A Feather Likeness of the Justice Chair."