Ian Brooks (born 1969) is a printmaker using traditional aquatint etching techniques to make atmospheric tonal landscapes. He has exhibited widely in the UK, with recent solo shows in 2022 and 2025, and a 2-person show in Stockholm in 2024. When not in the studio, he is also an academic scientist working on polar climate. @ian_m_brooks

How did your upbringing influence your art and your thinking about the world? I was brought up in the English Midlands, just north of the sprawl of Birmingham, on the edge of Cannock Chase, a large area of forest. A five-minute walk from home would take me into the woods, where I could, and did, wander freely throughout my childhood. That early freedom to explore open countryside instilled a love of the natural world. I’m much happier in the wilds than in a city.

When did you first fall in love with art and realize you wanted to be an artist? For you, what is the importance of the arts? I had always enjoyed drawing, but it was in my early teens that I found a real passion for the visual arts, and more specifically at the time with illustration: album and book covers, and graphic design. For much of my teens, I would have said I wanted to be an illustrator, but at the same time, I had always been fascinated by science and ended up studying physics, staying on for a PhD, and ended up an academic working on climate science. Art took a back seat for a long time before I returned to it seriously about 10 years ago.

Art is, I think, a big part of what makes us human. Science figures out how the world works, but art explores our place in it and provides a personal, emotional response to it.

What does your typical day in the studio look like? Walk us through your studio and your most-used materials and tools. Studio time is still fitted in around my academic work, mostly evenings and weekends. I have a small studio at home, but it’s a constant battle to find enough time to keep up the momentum on projects.

I am primarily a printmaker, working with traditional etching techniques. The images are acid-etched on copper plates, built up from many separately drawn and etched layers, and hand-printed in small editions.

I work almost exclusively with aquatint. The plate is coated with a fine resin dust that is heated to melt it, leaving tiny droplets fused to the plate and that resist the acid. The area between the resin beads is etched, producing a fine halftone when printed. Areas to remain unbitten are masked off by painting a stopout varnish over them. Positive marks can be drawn on with a sugar solution; once dried this ‘sugarlift’ is coated with stopout varnish, and then melted off in hot water, exposing the areas to bite. It’s a slow way to make work, but I love the process.

I usually ‘spitbite’ the plate, painting the acid on with a soft brush rather than immersing the plate in an acid bath; this enables a fine control of very subtle tonal gradations to be achieved – the longer the exposure to the acid, the darker the tone. The process is, however, subject to more than a little randomness since the artist is effectively working almost blind, and must respond to the result of each successive bite as the image evolves. When it works well, it produces something magical that no other technique can match; when it doesn’t…well, there’s always another plate.

The studio itself is pretty basic: a large draughtsman’s drawing table, a plan chest, and a desk with the press on. All the acid work is done on top of the plan chest, in plastic trays to keep it contained, with another tray of water to wash the plate. The aquatint resin is hand-dusted onto the plate from a jam jar with a bit of old shirt material stretched across the top, and melted with a plumber’s blow torch with the plate sat on a cake-cooling rack suspended from a nail in a ceiling beam. It’s about as simple and low-tech as you can get.

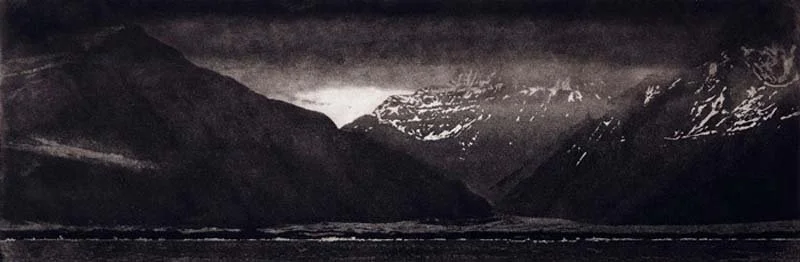

What projects are you working on at the moment? And what themes or ideas are currently driving your work? Right now, I’m trying to finish up a project started almost 2 years ago. I spent a week on a landscape sketching residency with Sail Britain – 6 artists plus 2 crew on a 40-foot yacht, sailing around the west coast of Scotland near Skye. I set out to produce a suite of etchings derived from the sketches I made, and I’m just working on a couple of larger pieces to wrap it all up.

A consistent theme running through these, and all my work, is an attempt to evoke a sense of place. By this I mean the unique atmosphere of a specific location and point in time – something that may vary with season, time of day, and the weather; an emotional response to the location and conditions at the time. It is important to me that this is specific to the actual location. I may vary the level of detail and realism of representation in the final etchings, ranging from tightly controlled drawing to quite loose semi-abstract mark making, but I’m not interested in abstracting things to the point that the landscape represented becomes generic. If you know the location, I want you to be able to recognize it.

What do you hope people feel when they experience your art? What are you trying to express? I hope they respond directly to the sense of place I’m aiming to evoke, and feel something of the atmosphere I was responding to. It is gratifying that some of the strongest responses I’ve received have been from people who have strong connections with particular locations. I have avoided trying to overtly link the art to climate issues, but I do hope that the work prompts an awareness of the fragility of much of the environment, and the polar regions in particular.

Which artists, past or present, would you like to meet? And why? Oh, there are so many who would be interesting to talk to. From the past, maybe James Whistler and Frank Brangwyn, representing opposite extremes in the revival of etching as a means of artistic expression rather than merely reproduction. Whistler: a master of pure drawing, delicate, and small in scale; Brangwyn: imposing, sometimes huge, often almost brash images full of energy and dramatic tonal contrasts. These are the two artists who first really got me interested in etching.

Do you draw inspiration from music, art, or other disciplines? I have hundreds of art books and exhibition catalogues, and other artists’ work is hugely inspiring. Those who most influence my thinking about my own work tend now to be painters or photographers rather than other printmakers, and increasingly those making abstract art.

Music is essential. It doesn’t directly inspire particular pieces of work, but it is always playing in the studio – mostly instrumental, often minimalist or electronic – and very much sets the tone for the work, with the music often being chosen specifically to what I’m working on.

What do you love about where you live? I love being able to walk straight up onto high, open moorland. I live just outside the village of Haworth in the Pennine hills of Yorkshire, and I often go out walking with a sketchbook, stopping to draw whatever catches my eye. Revisiting and redrawing the same places under different conditions is a great way of learning the local landscape.

Tell us about important teachers/mentors/collaborators in your life. I have no formal training in art, and work more or less in isolation. However, I might single out the late John Latham as a sort of inspiration. He was the head of the department when I started my degree, an eminent atmospheric physicist, and my PhD supervisor’s PhD supervisor. He was also an award-winning poet, wrote several radio plays for the BBC, and a novel. He’s a personal reminder that you can maintain a productive train is a tlife in both science and the arts at the same time.

Sustainability in the art world is an important issue. Can you share a memory or reflection about the beauty and wonder of the natural world? Does being in nature inspire your art or your process? I’m privileged that my scientific work has taken me to some very remote places: the central Arctic Ocean, the North Pole (twice), the Antarctic islands of Signy, South Georgia, and Bird Island. All beautiful, sometimes rather bleak, but hugely inspirational. Some of my favourite memories are of times working out on sea ice in the Arctic Ocean, the sense of isolation when it is almost possible to feel you are entirely alone. Most of this work has been based on ships, and I love being at sea. I’ve yet to figure out how to try and approach it in etching, but being out on the ocean in a big storm is wildly exhilarating.

AI is changing everything - the way we see the world, creativity, art, our ideas of beauty and the way we communicate with each other and our imaginations. What are your reflections about AI and technology? What is the importance of human art and handmade creative works over industrialized creative practices? I am mostly rather horrified by the generative ‘AI’ tools, or at least by the way they are being pushed by the tech companies as a shortcut to an output that removes the need for any technical skill or real thought. It’s a viewpoint that sees the world purely in terms of products and consumers, and completely misses the point of the arts – to communicate. It also fails to recognize that for many of us, the point of making art is not necessarily the end product, but the process of making it.

Exploring ideas, art and the creative process connects me to…Myself.