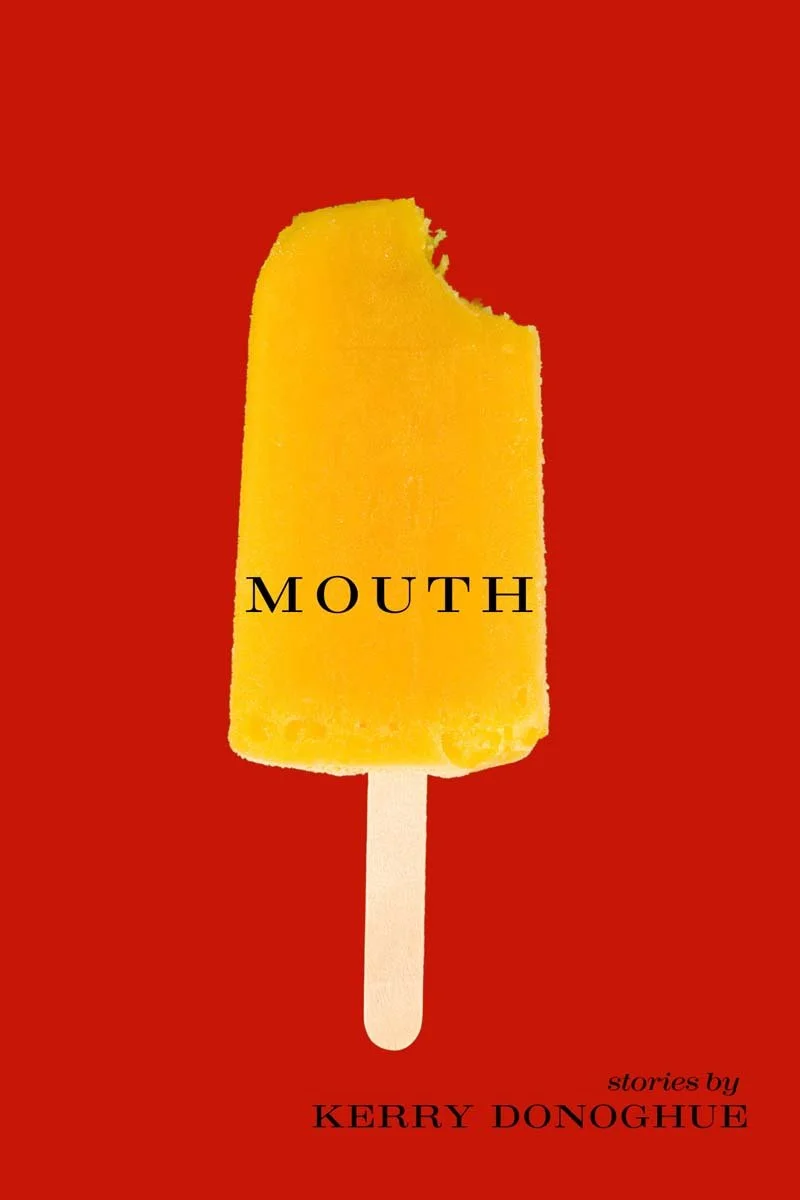

Kerry Donoghue’s poetry and stories have appeared in Ninth Letter, Painted Bride Quarterly, Permafrost, The Louisville Review, and The South Carolina Review, among other journals. She earned an MFA in Writing from the University of San Francisco. And she was a fiction cohort for the 2025 Poets & Writers Get the Word Out publicity incubator. She currently lives in the Bay Area with her family. MOUTH is her first book. @kerrydonoghue

Where were you born and raised? How did it influence your writing and your thinking about the world?

I grew up in the Colorform-scented suburbs of Los Angeles during the ‘80s and ‘90s. It was an era of fluorescence and flash, excess and indulgence. And it was also a time of earthquakes and the Nightstalker, so malls became a safe place for kids to hang out. Those days spent walking laps or eating Sbarro offered hours of observation, watching what people wore, what they ate, where they shopped. I became curious about how people decided what they consumed, and what those choices both revealed and concealed. What are we actually hungry for? It’s that tension between artificiality and authenticity, what’s hidden and what we desperately want others to see, that’s ingrained in me and intrigues me most.

When you were a child, what role did books play in your life?

Like many kids made smaller by alcoholism and religion, I used books as an escape and a path to figuring out who I was, or who I could be. The Choose Your Own Adventure series was instrumental in giving me that freedom to explore lives far less stifled than my own—and opened my eyes to the glaring differences of male protagonists.

I’d be lying if I didn’t also include romance novels from the ‘80s. Sure, I loved scanning them for all the illicit scenes, but their rawness showed me how the body didn’t always have to be shameful, the absolute opposite of the Catholicism I’d been ensconced in. Those novels were furtive lessons on power and self-determination, the importance of passions that didn’t involve impaled palms or the omnipresent eyes of judgment. Each lusty moment dragged me from the impossible perfection of the heavens and into the reassuring messiness of imperfect mortals. In them, I found the forgiveness to be myself.

Do you have a typical writing routine? Walk us through some of the steps.

My writing routine is just…chaos. I can’t even pretend I have it together. With two young kids, a full-time job, and ADHD, being scattered is my biggest boss fight, so I’ve found having a creative routine that relies more on intent and less on productivity works best right now. Every morning after school drop-off, I put my headphones in and walk along the local beach. Music helps me transition from the morning rush back into my body so I can slow down and access my creativity; that brief wander through nature, scanning for humpback spouts or eyeing falcons, centers me enough to set a creative intention for the day. Maybe my goal will be grand, like finishing a scene, but I also count submitting, marketing, and posting book-related content on social media. By breaking it down into one attainable achievement, I’ve found that I actually get more done. From there, I might eke out some words during my lunch break or on the sidelines at an afternoon soccer practice. But the quality writing usually happens around 10pm once there’s a quiet stretch of time that I can finally lock into. If my chocolate stash is solid, I’ll power up and write until midnight, feeling like a queen. But if I’m just too exhausted, then I can still find comfort in knowing I kept the admin side of my writing going. So while I may not write every day, I touch some aspect of writing every day. Like going to the gym or being in a long-term relationship, it’s a choice and I make sure I choose it daily.

At this point in my career, I’m getting better at establishing a writing regimen: drafting rough outlines before I dive in, or, god help me, using a spreadsheet to track everything in the novel I’m writing. Then it’s usually a mad rush to spill the words into a first draft. A very good writing night nets me about two pages, but most nights it’s just a solid paragraph or so.

Editing is my favorite part, though, and where I do the real work—I love excavating and rearranging and refining. Of course, this is where I also get stuck most often, unable to move on until it feels “perfect.” And I chase that idea of perfection through the remaining drafts, making all my edits on the screen until I think I’m “done.” Then I shift to making edits on paper to trick my eyes into seeing it differently. I’ll alternate editing between screens and paper, over and over, until it feels ready for my writing group to look at. Only then, after their eyes and maybe one or two more rounds of my own, I’ll finally feel gutsure and submit it.

If it gets accepted and they ask me to make any last edits, the terrible chase starts all over again. I can be kind of a monster that way, changing things until the editor reprimands me. I once took a career aptitude test in junior high and it said I’d be most successful as a bricklayer. I guess that ended up being true.

Tell us about the creative process behind your most well-known work or your current writing project.

MOUTH was a grueling lesson in patience. It took me 14 years to complete; I started it in my late 20s as my MFA thesis and finished it in my early 40s during the pandemic. Between then, a lot of life happened and several stories from it were published, but I could never get the whole collection published. I kept pushing on each story, tweaking scenes, revising, submitting, hoping, doubting myself. The revising felt right some days, like madness most of them. I’d gotten so many rejections that I ended up shoving the manuscript in a drawer, hiding my failure from myself. It stayed out of sight for a year.

Then, when I was stuck at home during COVID, I looked at it again with fresh eyes and got the tingle, which is when I realize a story is there. It felt surreal to write a story at age 28, but not have enough life experience to understand what was missing from it until 41. So I gave it one last revision, submitted it, and was shocked when it got picked up by Unsolicited Press for their Year of Womxn lineup, a year dedicated to amplifying womxn’s voices—the right home. Though I definitely grew on the page, the most poignant growth first needed to happen within me as I learned to finally trust my writerly instinct. To hone that was worth the wait. MOUTH ended up much stronger for it.

Do you keep a journal or notebook? If so, what’s in it?

I’ve been less about a notebook these days and more about taking photos, a COVID holdover I’m still enjoying. Before the pandemic, when I was going into an office every day, I had my notebook in my bag at all times to jot down phrases overheard on BART or quickly sketch out a scene. Now, I’m working from home with my laptop perpetually within arm’s reach, so it’s easy to add caught phrases to my catch-all Google doc. But when I’m on a walk or running errands, I’ve found I’m more drawn to capturing moments in visual form. Even if that means I currently have 35,377 photos on my phone. Ugh.

How important is background research in the kind of writing you do?

Exploration is part of the fun of writing for me; it takes me time to flounder and figure out what I’m heading toward, which often wends me through groups and places I know very little about. I’ve always felt a bit like an outsider myself and am drawn to the worlds of other outsiders. So when I’m heading into the unfamiliar, I rely heavily on research for accuracy and confirmation. My search history is bonkers.

Which writer, living or dead, would you most like to have dinner with, and why? What would you ask them?

I adored Patricia Lockwood’s book No One is Talking About This. It’s wholly unique in both its content and form, and I ping-ponged between cackling and crying the entire read. It was fantastic. I can see her being the perfect dinner companion for an evening of absurdity and hilarity at Medieval Times Dinner & Tournament.

Do you draw inspiration from music, art, or other disciplines?

I’m drawn to the tension between inhibition and freedom, and one place I can always pull it from is music. I admire musicians like Bjork, Karen O, Fiona Apple, and Neko Case, who relentlessly push boundaries. Their innovative songwriting, sound, and aesthetics inspire me to let my characters live full experiences on the page. Or at least intensify that battle inside them. I enjoy digging into the awkward, the darkness, the discomfort, things I tend to desperately avoid in my real life.

Maybe that’s why I also find a lot of inspiration in ballet, the physical embodiment of what’s unsaid. The unabashed emotion of the dance. The reminder that there’s gold in the risk. It’s what I’m trying to do with my words, and, on some level, my life.

We share an interest in ekphrastic writing—the conversation between the word and the image. I’d be interested in hearing your reflections or creative responses to my art?

Though Funk’s painting, L’Heure Bleue, initially looks like a gorgeous summer afternoon, I feel a lingering sadness that I associate with the loss of innocence in girlhood, that slow process of realization and internalization. I see it symbolized in the diminishing opacity and shortening hairstyles on the young woman as they progressively embody that loss while walking away. And I see it in each of their gazes as they start by looking out toward the water, a hopeful gesture, until, at the end, they’re looking down, which could be a shift to introspection perhaps, or shame, acceptance, maybe even sadness. And with a title that translates into “The Blue Hour,” there feels like a real emphasis on the in-between. I love how Funk’s artwork captures that “not quiteness”---of the day, the season, the age.

Your interpretation really surprised me and chimes with something I think about a lot, which is how can we maintain our innocence through maturity. I didn’t know that was coming through in that painting. I believe that is one of the great challenges in life, how to hold onto that sense of wonder and beauty throughout our lives.

AI and technology are changing the ways we write and receive stories. What are your reflections on AI, technology and the future of storytelling? And why is it important that humans remain at the center of the creative process?

AI is looting our souls. Literally and metaphorically. We’ve trained the machines to extract the essence of writing without understanding any of that essence, a soulless, vapid maneuver aimed at quickly teaching it voice and tone. But instead, it’s going unchecked, consuming and disposing of what’s taken years for an individual to create, just to train the algorithm. I’m so sick of the algorithms. Are we any better for them?

Tell us about some books you've recently enjoyed and your favorite books and writers of all time.

I’ve fallen in love with so many books this year:

Reservoir Bitches by Dahlia de la Cerda

I’m a Fan by Sheena Patel

Hot Girls with Balls by Benedict Nguyen

Outside Women by Roohi Choudry

The Secret Life of Groceries: The Dark Miracle of the American Supermarket by Benjamin Lorr

Leafskin by Miranda Schmidt

The Belles by Lacey Dunham

Sister Creatures by Laura Venita Green

When it comes to my favorite writers of all time, I’ll read anything by Jesmyn Ward, Paul Harding, Samantha Irby, Tommy Orange, and George Saunders.

Exploring literature, the arts, and the creative process connects me to…

the roots of our shared humanity. When I’m writing, or reading, or wandering through an exhibit, it’s as if I’m aiming a little heat at what’s hidden inside me, replenishing it with water, and then coaxing it to grow wide. It feels like community, or rejuvenation. Like healing.