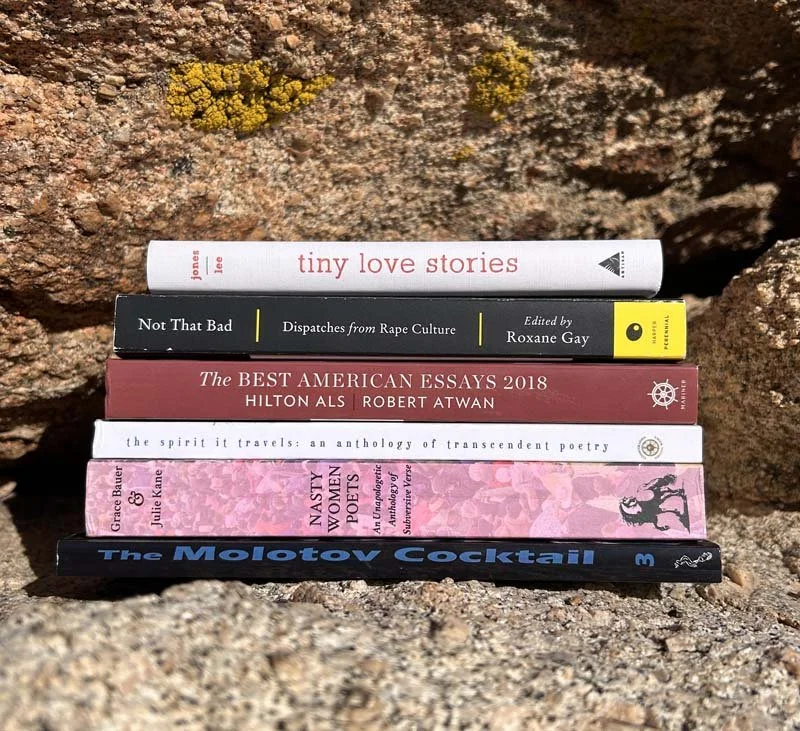

Lisa Mecham is an artist living in California. Her work has appeared in publications such as The New York Times: Tiny Modern Love, Roxane Gay’s bestselling anthology Not That Bad: Dispatches from Rape Culture, and Huffpost Personal, where her essay about ending her marriage went viral. She’s served as a Senior Features Editor for The Rumpus and now works as a freelance editor, helping writers bring what’s in their head and heart fully onto the page.

Lisa’s work explores what shame has silenced, offering others permission to do the same. She’s drawn to thresholds—between logic and magic, wildness and restraint, seeming and being—and believes in the power of language to reveal our truest selves. @lisa_mecham

Where were you born and raised? Would you say it impacted your work?

I was born in American Fork, a small town in Utah settled by Mormon pioneers in 1850. Both of my parents were raised there as well. The town was named in the parlance of early trappers for the branching river that runs through it. I was a practicing Mormon until around twelve years old, when my parents left the church, but the patriarchal order at the core of its teachings and organization has lingered — an invisible scaffolding I have spent decades unlearning.

Has reading always been a part of your life? What were some of the books that made you fall in love with reading?

It's hard to imagine a time in my life when I wasn't being read to or reading for myself. Family lore says I knew the alphabet by eighteen months. As a little kid, I loved the Little Golden Book series and memorized every poem in "A Rocket In My Pocket" and then later "Where The Sidewalk Ends." My father read to me and my siblings before bed, and the worlds of Alice in Wonderland, The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings became foundational texts for me. All the Beverly Clearly books and John Bellairs. Nancy Drew and Sweet Valley High. Madeline L'Engle and Zilpha Keatley Snyder. Roald Dahl. Every dollar of babysitting money went towards books, and the library was my second home.

Describe your typical writing day.

I don't believe in anything "typical" when it comes to writing; I mean, life just doesn't work that way. I tend to do my best creative work at the bookends of the day: before sun-up and after sundown, the hours where the world feels strange and numinous. Writing is part craft, part mystery and I find the mystery part is easiest to access in those liminal spaces.

When I'm working on a project, there's usually a hump I have to get over—a hump of fear where I've convinced myself of three things:

1. I'll never be able to get what's in my head onto the page.

2. If I do, and dare share it, I will be rejected as some grotesque monster.

3. Do I even know how to write?

But if I sit with myself, breathe, and just start...then the magic happens. I don't outline but I do often tape a giant piece of paper across my desk and start sketching a sort of map—images, ideas, threads. Once I see it laid out, I can fall into flow.

I try not to edit until a draft is done, because the perfectionist in me is always searching for a way to sabotage the vulnerability it takes to write in the first place.

What was the creative process behind your most well-known work?

In 2024, Huff Post published an essay about my divorce that, as the kids say, went viral. I mean, millions of people read it. I was not prepared for that kind of exposure, and while there was a time when I might've thought that was the dream, I'm not so sure anymore. Still, I'm deeply proud of the piece. It began as a memoir about living in a tony town in Connecticut with two small children as my husband lost his mind. That manuscript got me my agent—who, in an unexpected twist, advised me NOT to publish it. At the time, that was confusing and devastating to hear, but she was right. The story was too close, too raw, and I would have hurt people I love. So I waited. I'm grateful she had the courage to say that to me. The story as I had written it then was too close to the pain of what happened and I would have hurt people in my life with the way I was telling it. So I waited. Over time, the grief transformed, into language, into art. That's when the source material found its truest form. Somehow, in just a few thousand words, the essay I wrote captured everything the book once tried to say.

After it ran, my inbox filled with hundreds of messages from readers who shared their own stories of living through simliar situations. That response was profoundly moving. But it was also followed by another kind of reaction: after Trump's election, the piece was circulated among men's rights forums, and I began receiving violent threats and cruel messages. Still I wouldn't take it back. Publishing that essay taught me to trust that art can hold both the tenderness and terror of being alive.

Do you keep a journal or notebook? If so, what’s in it?

I keep many! I find them at Japanese stationery stores because they carry all my favorites. I have a journal for craft lessons, one for therapy insights, and separate journals for each project I'm working on. Each one serves a different purpose and they help me make sense of things: the practical, the emotional, and the creative.

How do you research? What role does research play in your writing?

The root of the word "research" means "to search again" and that feels true to my process. I'm out in the dark, flashlight in hard, circling what's mysterious until it begins to reveal itself. For personal writing, I turn inward to old journals, half-formed notes, and memories. For nonfiction or journalistic work, I go outward to books, archives and the internet. When I'm drafting, I'll throw all my notes and ideas into a giant word document so they're all safely contained, then I go about cutting, pasting, moving and shaping.

Which writer, living or dead, would you most like to have dinner with, and why? What would you ask them?

Stephen King. He is the reason I wanted to pursue writing seriously. I even published a short story called All Roads Lead Home where he and his house in Maine are the engines of the piece.

I have been his Constant Reader (to borrow his term) since my teenage years. He feels like a companion, not a performer. He writes about ordinary people. He takes what is unbearable about being human and trusts the form of story to hold it. As a writer, he always shows up for his work. Snobby writers look down on him, which never ceases to make me laugh.

I don't imagine we'd go out for dinner so much as sit together at a Red Sox game. Shooting the shit in between innings and hot dogs. I would give anything to tell him "thank you" in person, for being by my side for every version of myself.

Do you draw inspiration from music, art, or other disciplines?

All art moves me. I always listen to music when I write: ambient and film scores are my favorites. I still attend the symphony in person because classical music feels like the language of my soul. I grew up singing and playing the piano, so melody is how I first leaned to understand and express emotion.

Film has always been a teacher—the way it compresses vast ideas into something you can feel in two hours. the ability to capture the ephemeral on screen. And ever since my fifth-grade field trip to the St. Louis Art Museum, I've been drawn to visual art. How a single image can say what a lifetime of words might only approach.

AI and technology are changing the ways we write and receive stories. What are your reflections on AI, technology and the future of storytelling? And why is it important that humans remain at the center of the creative process?

At this moment, AI feels less like a creative revolution and more like a glorified search engine — a closed loop feeding on the internet, a circle of data regurgitating itself and calling it innovation. It’s another tech-driven grift dressed up as progress, convincing us that we can’t live without something we didn’t need in the first place.

As a freelance editor, I’ve already seen the results: writing that’s been clearly churned out by AI — lifeless, hollow, formulaic. It’s depressing, not because it’s “bad,” but because it has no pulse. There’s no risk, no memory, no mystery.

The essence of storytelling isn’t in data. It’s in consciousness — the lived, contradictory, deeply human experience of being here. No algorithm can reproduce that spark that happens when a writer reaches for the ineffable and finds just the right word. Technology will keep changing, but the beating heart of story will always belong to us.

Tell us about some books you've recently enjoyed and your favorite books and writers of all time.

Recent books: Writing, Creativity and the Soul by Sue Monk Kidd; The World of Inner Trauma: Archetypal Defenses of the Personal Spirit by Donald Kalsched; Against Platforms: Surviving Digital Utopia by Mike Pepi; Poetics of Music in the Form of Six Lessons by Igor Stravinsky; and, Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea: A Veteran's Memoir by Khadijah Queen.

All time favorites: Everything by Stephen King; In Cold Blood by Truman Capote; all of Anne Sexton & Sylvia Plath's poetry; Jamie Quatro; The Soul's Code: In Search of Character and Calling by James Hillman; Wallace Stegner; Stoner by John Williams; Tomas Tranströmer's; Elizabeth Strout; Roxane Gay; Morgan Parker; Elena Ferrante; Gabriel García Márquez; Roald Dahl; John Updike; Mrs. Bridge by Evan A. Connell; I COULD GO ON FOREVER!

Exploring literature, the arts, and the creative process connects me to…

the part of me that is the “being” part, not the “seeming” part. I used to think I was supposed to seem my way through life. Seem perfect. Seem happy. But art — and the uniquely human impulse to create — has brought me into the world of being, even though it can be painful at times. To really be myself.

Exploring literature, the arts, and the creative process reminds me that aliveness isn’t always comfortable, but it’s real. It asks something of me — honesty, attention, surrender. When I’m engaged with a piece of writing or a work of art, I feel less like I’m performing and more like I’m listening — to the world, to others, to something larger that’s moving through me. The creative process gives form to what’s ineffable, and in doing so, it allows me to live more truthfully.