Selena Mercuri is a Toronto-based writer, editor, book reviewer, publicist, and social media manager. She is currently an MFA candidate in Creative Writing at the University of Guelph. She also holds a BA in Political Science from the University of Toronto and studied Publishing at Toronto Metropolitan University.

Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in The Fiddlehead, The Literary Review of Canada, The Dalhousie Review, Room Magazine, Prairie Fire, The Ampersand Review, The BC Review, The Seaboard Review, The Hart House Review, and The Trinity Review, among others. She was the recipient of the 2023 Norma Epstein Foundation Award for Creative Writing and a finalist in the 2024 Hart House Literary Contest.

In addition to her creative practice, Selena works across the Canadian literary landscape as publicist at River Street Writes, reviews editor at The New Quarterly, and social media associate at The Rights Factory. She also produces Coffee Dates with Authors, a weekly Substack interview series spotlighting Canadian writers. She is currently querying her debut novel, SMOOTH JAZZ AND OTHER FORMS OF TORTURE. @selenamercuriwriter

Where were you born and raised? How did it influence your writing and your thinking about the world?

I was born and raised in Toronto, but my family constantly moved around the province, which meant I attended six different elementary schools before settling down. This nomadic childhood profoundly shaped both my writing and worldview in ways I'm still discovering.

Perhaps most obviously, my work deals extensively with themes of displacement and the psychology of unfamiliar environments. There's something about being perpetually the new kid that teaches you to read rooms quickly, to notice the subtle social currents often taken for granted. You develop an outsider's eye even when you're technically an insider. Since I never really had the opportunity to take root in any one place, I developed what I think of as a kind of geographical transcendence—an ability to feel simultaneously at home and foreign wherever I am.

Looking back, I think those early years of adaptation and re-adaptation gave me both the restlessness that drives my creative work and the empathy for displacement that runs through much of what I write.

What kind of reader were you as a child? What books made you fall in love with reading as a child?

I was an obsessive reader as a child. My family owned a small Latin restaurant, and there was a library across the street. I'd spent my days there while school was out for the summer, sometimes for six to eight hours like I was clocking in for a shift. My very early obsessions included A SERIES OF UNFORTUNATE EVENTS by Lemony Snicket and DEAR DUMB DIARY by Jim Benton.

This might seem a bit ironic since I struggled with language early on—I needed speech therapy, had classroom writing support, and an IEP. I wasn't a good student by conventional measures.

The first book I bought with my own money was DOCTOR SLEEP by Stephen King. I was probably too young for it, but I loved how King made the impossible feel inevitable.

High school changed everything. An English teacher motivated me to feel more confident in myself. I spent lunch hours in the school library, falling in love with books like A STREETCAR NAMED DESIRE by Tennessee Williams, ANIMAL FARM by George Orwell, and TO KILL A MOCKING BIRD by Harper Lee. The librarian saw what I was reading and recommended I be moved into an advanced English class in grade 11. It was quite the turn of events.

When I switched schools in grade eleven due to family conflicts, another English teacher brought me a bag of books as a gift: EMANCIPATION DAY by Wayne Grady, THE LAND OF DECORATION by Grace McCleen, and THE GIANT'S HOUSE by Elizabeth McCracken. The gesture meant a lot to me, and I still have all those books.

Describe your typical writing day.

I wish I could describe a typical writing day, but between working as a book publicist at River Street, Reviews Editor at The New Quarterly, and social media associate at The Rights Factory—plus my MFA program—there really isn't such a thing. I've learned to write at all times of day and just about anywhere: on transit, between meetings, in coffee shops, sometimes even on my phone while walking (sorry if I bump into you!).

When it comes to process, I'm still figuring out what works best for me. I don't normally outline when I'm writing short stories—I prefer to let them unfold organically and see where they take me. But when I was working on my recent book, my first, I kept getting completely stuck without a roadmap. The only way I was able to finish it was by forcing myself to outline, even though it felt unnatural at first. It taught me that different projects may demand different approaches.

I definitely edit as I go, sometimes to my detriment. I can spend hours perfecting a single paragraph instead of pushing forward with the draft. I recently learned that poet Lisa Richter is experimenting by having her monitor off while she writes—I may need to give that a try sometime!

Tell us about the creative process behind your most well-known work or your current writing project.

SMOOTH JAZZ AND OTHER FORMS OF TORTURE grew out of my fascination with the absurd cruelties of everyday life—those small, persistent irritations that can feel genuinely torturous when you're trapped with them.

The novel follows Lana Arenas as she navigates the aftermath of her family's collapse—her father's abandonment, her mother's detachment, and her struggles with disordered eating. What interests me is how trauma manifests in the mundane details of daily life: the way Lana uses food as both comfort and punishment, as the one thing in her life she has control over.

The creative process involved a lot of sitting with uncomfortable emotions—the exhaustion of depression, the confusion of growing up and not understanding your own desires or sexuality, the way people closest to you often hurt you the most. Fundamentally, it's about the difference between surviving your life and actually inhabiting it.

Do you keep a journal or notebook? If so, what’s in it?

I like the idea of keeping a journal and have tried several times over the years, but it's probably just not for me. There's something about it that just feels overwhelming. I think part of the problem is that I put too much pressure on myself to make each entry meaningful or insightful, when really a journal is supposed to be a place for the mundane stuff too. I need to figure out how to give myself permission to be messy and scattered.

Which writer, living or dead, would you most like to have dinner with?

This is such a tough one because so many of my friends are writers and I'd love to have dinner with all of them—there's something special about sitting around a table with people who understand the particular neuroses that come with trying to make a living from arranging words on a page.

But if I had to choose, I'd go with Emma Donoghue. I recently reviewed her latest novel THE PARIS EXPRESS and absolutely loved it. She has this incredible ability to find intimate human stories within larger historical movements, and her characters always feel so real and lived-in. I also love that she included a sentient train in the book—how cool is that!?

I'd probably spend half the dinner asking her about her research process because she inhabits these different time periods and voices so convincingly. The other half would probably be about the sentient train.

Do you draw inspiration from music, art, or other disciplines?

Definitely. I've been experimenting with making digital collages lately, which has been surprisingly liberating. There's something about working with found images and text that bypasses the usual perfectionism I bring to writing. You can layer meaning in ways that feel more intuitive than deliberate, and the accidents often turn out to be the most interesting parts.

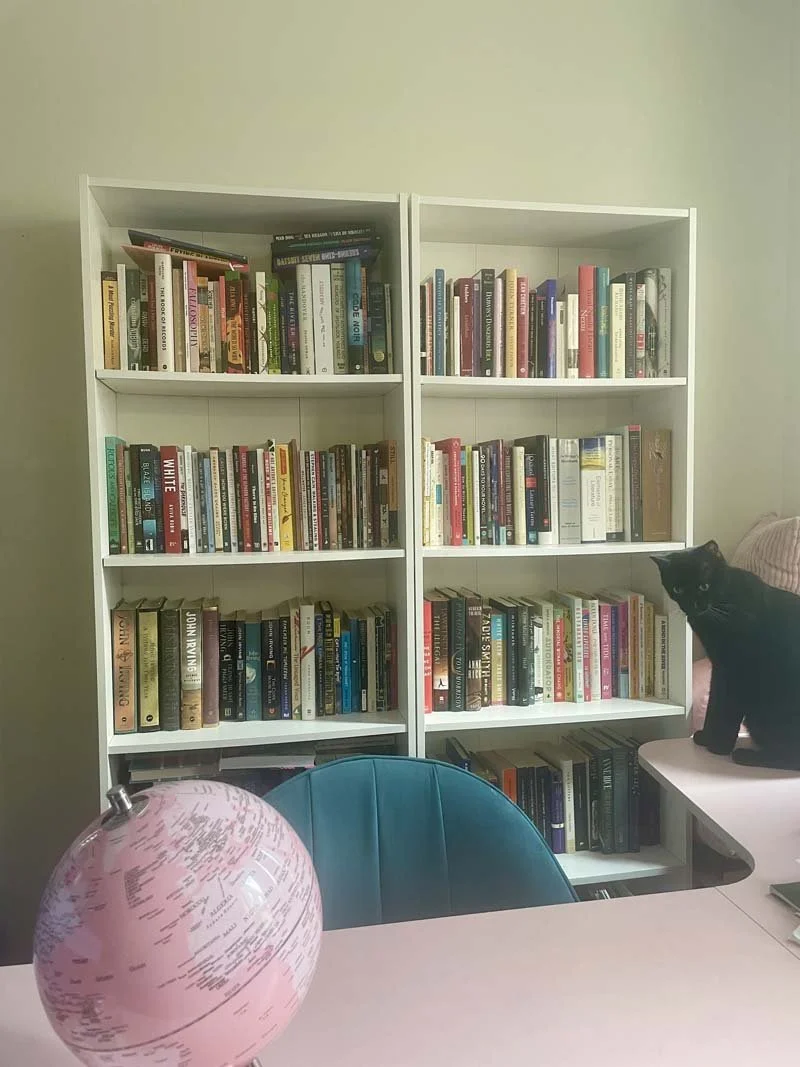

I've also been experimenting with blackout poetry using political theory texts—my BA is in Political Science, so I have all these dense academic books lying around. There's something deeply satisfying about taking these often impenetrable theoretical frameworks and finding the emotional core hidden inside all that jargon. You're literally excavating poetry from prose, revealing what's already there but buried under layers of academic language.

Most recently, I did one using Christine de Pizan's The Book of the City of Ladies. Working with her text was incredible because she was already so ahead of her time in terms of defending women's intellectual capacity and moral authority. The blackout process helped me find these moments where her medieval language suddenly feels completely contemporary—like when you isolate certain phrases about women's resilience or the ways patriarchal structures try to diminish female achievement, and it could have been written yesterday.

Both practices feed back into my fiction writing in unexpected ways. The collage work has made me more conscious of how images and symbols can carry emotional weight, while the blackout poetry has taught me to pay attention to the music that's already present in language, even in the most unlikely sources. Sometimes the best writing comes from learning to see what's already there rather than trying to create something entirely new from scratch.

It's also a way to keep my hands busy when the novel writing feels stuck. Different creative outlets seem to access different parts of the brain.

AI and technology are changing the ways we write and receive stories. What are your reflections on AI, technology and the future of storytelling? And why is it important that humans remain at the center of the creative process?

AI and technology are fundamentally changing how we create and consume stories, and I find myself both fascinated and deeply concerned by these shifts. We're living through a moment where machines can generate text that mimics human creativity, but there's something profoundly unsettling about the idea that storytelling—which has always been about one human consciousness trying to communicate something essential to another—might become automated.

Paul Vermeersch's latest poetry collection NMLCT grapples with exactly these questions, and he's been such an important voice advocating for keeping AI out of creative work. His poetry explores what happens to meaning when language becomes detached from lived experience, when words lose their connection to the messy, complicated reality of being human. Reading his work reminds you that poetry isn't just about arranging words in pleasing patterns—it's about consciousness trying to make sense of itself through language.

Humans need to remain at the centre of creative work because storytelling is ultimately about connection, about one consciousness reaching toward another across the void of individual experience. That's not something that can be automated, no matter how sophisticated the technology becomes.

Tell us about some books you've recently enjoyed and your favorite books and writers of all time.

I don't really have favourite books and writers of all time because I'm really bad at decisions and that feels like too much pressure. That said, here are some incredible books I've been loving lately:

-YOU'VE CHANGED by Ian Williams (fiction)

-THERE IS NO BLUE by Martha Baillie (Memoir)

-THE WORLD AFTER RAIN by Canisia Lubrin (poetry)

-WIDOW FANTASIES by Hollay Ghadery (short fiction)

-WHITE by Aviva Rubin (fiction)

Exploring literature, the arts, and the creative process connects me to…

a larger conversation that's been happening across centuries and cultures—the ongoing dialogue about what it means to be human, to struggle, to find meaning in chaos. There's something comforting about reading a poem written hundreds of years ago and recognizing your own experience reflected back at you, or discovering a contemporary writer grappling with the same questions you're wrestling with in your own work.