Everything is Art. Everything is Politics.

I think art competes with reality. And art will give you the last words.

–Ai Weiwei

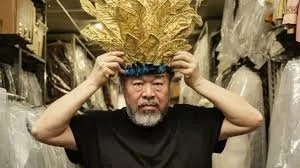

The renowned artist and activist Ai Weiwei has used sculpture, photography, documentaries, and large-scale installations to challenge authoritarian power for decades. But his project at the Rome Opera House, directing Puccini’s final opera, Turandot, may be his most powerful fusion of art and politics yet. Puccini’s original is a fairy tale set in ancient China about a princess whose riddle game costs failed suitors their lives. But Ai Weiwei transformed this story into a stark reflection of the present, weaving in footage of refugee crises, COVID hospitals, and the Ukraine war—a production that became an urgent act of resistance for its Ukrainian conductor and cast. The opera and documentary are a living document of our turbulent times, embodying Ai Weiwei’s belief that 'Everything is Art. Everything is Politics.'

The new documentary, Ai Weiwei's Turandot, goes behind the curtain to capture the artistic struggle and emotional weight of making this work—a process that began with one vision and was fundamentally changed by a global pandemic and a major war.

My guest is the documentary’s director, Maxim Derevianko. He grew up in a family with deep ties to the Rome Opera House, and he offers a deeply personal, intimate look at how in Ai Weiwei’s words, “art competes with reality, but art will have the last word.”

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

So your documentary, which I loved, is a work of art in itself, documenting the creation of a work of art's documentary. I mean, you really have this personal tie. We'll go a bit into your personal history, but you know the Rome Opera House very well. You're not just coming in on a commission to do one documentary.

You have a long history of telling their stories and knowing it from your various family members who have performed there. So this is truly behind the scenes, and your documentary opens with that Ai Weiwei quote, as I mentioned, "Everything is art, everything is politics." How did you set out to illustrate this statement? Because it seemed like the deeper we went into production, the world around the art grew more and more politically charged.

MAXIM DEREVIANKO

So when we decided to do a documentary to follow Ai Weiwei, we knew, of course, it wouldn't be just a simple opera, and we knew he would bring his own very special and original vision. Because, of course, he is not an opera director. From his point of view, it's a challenge, but from another perspective, it’s probably an enrichment for the opera audience because he doesn't follow the rules of opera, let's say it like this. And, of course, once you decide to do a documentary about Ai Weiwei, it's in his DNA to be political. Once I started to follow him, the political issues and topics came into the documentary by themselves.

I wanted to make a documentary, and my question was, "What is art, and why do we need it?" I had been asking myself this for a long time, and I had been working at the Rome Opera House since 2015 as a filmmaker, mainly doing commercials for them, trailers for each production. But every time I was there, my question was, "Why is this happening?" I mean, why are there people believing in a story of love, with other people just singing for two hours with costumes and music? You go to the theater, and you believe in this. If you take it out of the theater, I don't know if you would see people expressing that way in the streets; you would think that's ridiculous. Just expressing love or another concept through singing, you would just talk about it. But in that environment, you believe in it. So my question was, why do we need it? Why do we do it that way?

Together with Michele Cogo, Silvia Pelati, and Eugenio Fallarino, the writers, we went through the 2020 season of the Rome Opera House. We saw that Ai Weiwei was coming, and I said, "Okay, this would be an incredible production where we could try to find answers to those questions."

So while I was searching for answers, of course, the topics that Ai Weiwei always brings with him arrived: refugees, political issues, dictatorship, totalitarianism, freedom of speech, and everything. Basically, it all started from just one question that Puccini made for us: "What is love?" So we are all trying to answer this question or probably will keep answering it for the next million years because it will change all the time.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

You address those important questions: What is art? And why do we need art? Then we see the world in terms of a real shakeup in our education system. We see that the arts are kind of set aside, not seen as important and not contributing economic value. The work of artists is being scraped by AI with no compensation. There are so many ways in which artists are set aside as something not essential, but I agree with you; I think it is essential. So, why for you is what makes art essential and important? What is the importance of the arts and the humanities for you? How has it inspired your own work, and how does it enrich your life every day?

DEREVIANKO

When I started this documentary, I had this question, and after COVID arrived, it became very clear. I wanted to show you that when everything was taken away, people just got mad. I mean, you truly go crazy without the possibility of expressing yourself. You don't have to be an incredible, great artist. Even the people who started painting during the lockdown did so just because they had fun. That's our tool because it's expression. There were people singing on their balconies or playing music in the afternoons. I saw with my own eyes that it was a physical need, even when there weren't places where art could be put.

Of course, museums were closed, theaters were closed, and cinemas were closed. Everything was closed. Naturally, people found a way to do it. That means it is part of our nature, inside of our needs, just as much as eating. You can survive, I don't know, a couple of days if you don't listen to any kind of music, read any kind of books, see any kind of paintings or sculptures, or anything. You go crazy.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

It's very fascinating because Ai Weiwei says at the beginning that he doesn't have much connection to music or opera. He works in other mediums, but for him to have this long connection to the material and the choreographer is really fascinating.

Before we go further, tell us your own connection and your family's connection to the Rome Opera House.

DEREVIANKO

So, I mean, the reason why I wanted to do a documentary actually started a little bit more than 100 years ago. My great-grandfather became, in 1922, the first violinist of the Rome Opera House Orchestra. Then in 2015, I started as a videographer for the Rome Opera House. Well, of course, I went to film school and everything, and I always wanted to do a feature-length movie. So I started there, but I knew I didn't want to stay forever. That place was really deep inside my family. My mother also became a ballet soloist for the Rome Opera House.

Every time I stood in front of the orchestra pit, looking at the empty orchestra pit, I was almost hypnotized because I said, "It's incredible that 100 years ago, my great-grandfather was sitting there, and now I'm here with a camera filming." I wondered: is it just by chance or is it destiny? Is everything written? Should I be here? I don't know. It just triggered some interesting questions. I thought, "Okay, I have to leave this place; I want to live with something that is really important for me." So I decided to do a documentary, but I didn't want to make it about the Rome Opera House in general. I wanted to focus on the lives of the people inside the Rome Opera House and how many people work hard behind the two-hour show that the audience doesn't realize brings together so many lives to deliver just an emotion or a message.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

So yeah, just tell us the background of this piece of music we’re listening to, "Dimmi il mio nome."

DEREVIANKO

So that's what's happening in the story of Turandot. But I used it in a specific moment of the documentary because the whole documentary is basically layered on three different levels. We follow the story of Turandot. There is the princess who says that whoever wants to marry her has to face three riddles. Anyone who can solve the riddles will marry her. Of course, she kills everyone because no one can solve them.

We have the story of Ai Weiwei. We need to understand who Ai Weiwei is and why he does his art. And yes, we need to know why he is so important. So we start to discover who Ai Weiwei is. Then there is the last layer that follows our production, including the documentary production, because we all had to go through very similar steps. We used the story of Turandot as a metaphor for Ai Weiwei's life because we have Calaf, who is an exile just like him.

Just like him, he fights against tyranny and, of course, against the Chinese dictatorship. We all had to face our own big challenges. So that moment when Calaf solves the riddles is exactly the moment when he faces his challenge. The challenge is the three riddles. Ai Weiwei's challenge is to manage to endure his imprisonment of 81 days. He manages to do this because his art and ideology of freedom of speech involve so many people around the world that it became bigger than him. The Chinese government couldn't just make him disappear because otherwise, they would admit they were not a free country, as they claim.

Together, even in the documentary production, we all had to face our challenge, which was COVID-19. Even if it’s not a political enemy, it still tried to shut down the arts, trying to shut down life in general. We couldn’t move, we couldn’t express ourselves, we couldn’t share.

How did we do that? Through art. In Italy, the lockdown was very heavy. At some point, we became the first country in the world to experience the virus. People remember that we got through the pandemic because during the lockdown, we could do things like watch movies, read books, or paint again. Some people took their guitars and started to play. You can see that in moments of difficulty, art arrives and saves you because you need to express yourself and communicate.

So then there is this moment in the opera where Calaf says, "Okay, I won, but now you have to solve one riddle." Just at the end of the aria, for the first time and the last time, you start hearing the musical theme of the "Nessun dorma", which is, of course, probably the most famous piece of music ever written. It then becomes a hymn of hope because after this darkness, you start to see the light.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

It's so beautiful. And what it says is that for those of us who don't speak that language, we can understand it. We understand the feelings; we get the essence, and it is so universally touching. It is also an ode to hope, but of course to resilience, as we discussed. It captures the beauty and wonder of the natural world because it’s about tomorrow being another day that we can see on the horizon. So it connects us to this essential beauty of nature as well. As an artist, how do you connect to the beauty and wonder of the natural world and your memories of that? How does that fuel your process?

DEREVIANKO

We noticed that the aria of "Nessun dorma" has two parts. One part is dark when you play; it is actually the theme, and it's dark. The second part is positive; there is light. At some point, we said, "That's incredible," because in one aria we have two themes. We used one for the darkest moments of the documentary and the other for the bright moments of the documentary.

When the earthquake happened, we used the dark part. When Ching Chang talks about how he met Ai Weiwei, we used the positive part. It was important to me. You cannot compete with Puccini. And once you have to work with that kind of music, you know you just have to step back. So together with the composer, we decided to rearrange the same exact music.

We found these two themes inside the same piece, which was incredible. The audience never leaves Puccini since the beginning, and I think it's very beautiful.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

I think that’s a beautiful way that music, in particular, connects all life. At the end of Turandot, we hear the transition from dark to light, from the end of night to the coming dawn. In another way, while it's a celebration of beauty, resilience, and struggle, it also celebrates the beauty and wonder of the natural world that we can all connect with. Even if we don't speak the language, we just get the feeling of it. It rekindles our most basic and immediate response, and we can feel the dawn coming.

DEREVIANKO

For me, of course, nature is very important. I don't know if you remember, but during the lockdown, nature almost overcame the cities. There was this incredible thing in Venice: all the canals were so clear that you could see the bottom. The boats weren’t going like they used to. In just two or three months, the world changed completely—from the sounds of the cities to the air and the water. That was incredible for me. I think that, in general, nature is important.

Of course, in this documentary, I didn't work on that, but that's the other beauty of art. If you feel it and have that kind of interpretation, then it's right. My message just wants to arrive at the other side, and if that person takes it and re-elaborates it in another way, that's correct anyway. So, yeah, that's the power of art.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

Yes, it’s a frequency that we can all tune into, we must never close our ears to it. In closing, as you think about the future, as you think about the kind of world we’re leaving for the next generation, and as you think about those things that you’ve learned from your artistic family along the way, what would you like young people to know, preserve, and remember?

DEREVIANKO

I don’t like to give quotes or keys to lead your life, but I was thinking, especially these days, we are surrounded by war and politicians who seem to be going mad. What I saw in Italy, but of course also in the U.S., is the amount of money being spent on armies and guns—billions upon billions. I started to think, "What will happen if you spend the same exact money—not only on culture but also on schools and all these things?" You could completely change the landscape.

I know that, that’s a utopian thought, but what if we didn’t have any armies anymore, and we put all that energy into forming new people and giving them the instruments to see life in a certain way? I feel like war will always be part of human nature, unfortunately. But what if we did something like this? Probably people would start creating, composing the best music, writing the best books, and I feel that would be something incredible—to challenge or to show supremacy based on the cultural level of a country or something like that.

I just feel this is actually possible. I don’t think it’s just madness or something crazy that came to my mind. If money were invested in culture and education, the whole world would change dramatically because people would have the tools to understand the world around them. They would understand what is respect. They wouldn’t be ignorant anymore.