There's something fundamental about the value of art and culture. Not just being integrated for vocational reasons, but because the experience of art and having a cultural element in one's life brings enjoyment, learning, relief, or any of the many experiences and feelings that art provides. I think this is quite fundamental as an element of life. Creativity is key in any career and also in personal life, especially in terms of problem-solving, relationships, kindness, compassion, and empathy. The arts, creativity, and the cultural world at large are not just nice to have; they are essential. Their value is fundamental, although sometimes it's extremely difficult to define. To see the arts lost from the developmental moments in one's life is tragic. Developmental moments in life come at all points in the arc of one's existence. To see that taken or diminished is unfortunate. Everyone involved in working with artists, artists themselves, or those who are creative knows this and believes in it.

Today, we have with us a figure from the heart of the London art scene, Hannah Barry. At a moment when the art world often feels centered on global mega-galleries, Hannah has cultivated something truly unique in Peckham. With her gallery and the ambitious non-profit, Bold Tendencies, she has created a vibrant platform for a new generation of artists, taking risks and championing experimentation. She has been pivotal in shaping careers and bringing ambitious projects to life. We'll talk to her about the mission behind her work, her journey as a gallerist, and her latest exhibitions, including The Garden, with the photographer Harley Weir.

HANNAH BARRY

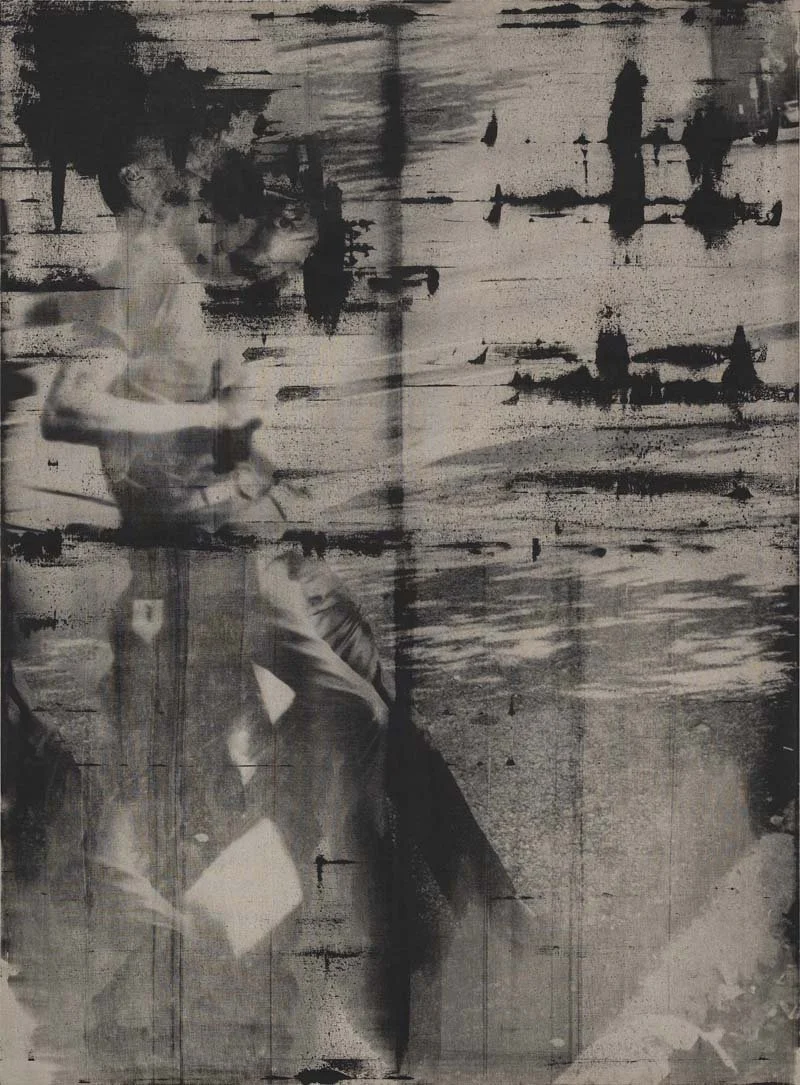

This is the second exhibition we've made with Harley Weir. The first exhibition was called Sins of a Daughter, which was an introduction to Harley's work and world. That was the first exhibition of her work to take place here in London. For the follow-up exhibition, titled The Garden, Harley had a very specific idea of what she wanted to present in terms of materials and the place she was in her life at this point in time. The garden is an all-encompassing term that she uses to refer to where she has come from and where she is going.

Of course, the garden draws upon universal symbolism—multiple meanings, such as a place of birth, growth, and death, as well as a place of renewal and change. It serves as a mystical and magical place, a sort of dream place as well as a Utopian type of thinking. There are many ways in which the garden is relevant to Harley at this point in time, and the works we are showing come from across all her practice.

Some of the photographs displayed downstairs were taken more than ten years ago, but were printed specifically for the exhibition. Harley has explored numerous materials she has worked with over the years to create this singular presentation of the garden, where she feels she is at right now.

The show includes images of birth and very personal images of illness. Her father, who has a very rare form of dementia, is represented in photographs that are some of the only ones Harley has taken of him at this time. These images stand out as containers for many feelings and ideas, while, in contrast, the images of her father reflect a different narrative—his mind is emptying out while his body remains. This has been quite a privilege to show alongside all the other works.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

A lot of us are, of course, talking about AI. We had Trevor Paglen on recently, and he critiques technology a lot. I think many of us are living this flattened life, so invested in screens and AI-generated outcomes that we don't realize we're missing the process. Everything is so fast that we lose the beauty of slow discovery and innocence; everything is just done. I am wondering what your reflections are on this and how we can hold onto our humanity and creativity in the face of such rapid change.

BARRY

One of the amazing things about the process of creating art is that there is a making involved, regardless of the format it takes. Someone somewhere is doing something to determine that. This act of making is anything but flattening; it is illuminating, enriching, evolving, and progressing the material available for those of us who engage with art. I believe it is a truly enriching experience.

Of course, I acknowledge that our lives, particularly over the last 20 years or so, have become more engaged with a flat world—a world represented on screens. However, that's only the dominant portal through which we experience things. What lies behind that is a vibrant act of making, which is rich and three-dimensional.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

It's not always pointed out how gallerists or curators are storytellers, and I've found through my conversations that sometimes visual artists are not the best tellers of their own stories. They express their narratives through paint, photography, or their medium. Some also write or make films, but they don't always verbally articulate their stories; they have the feelings that inspire their visual art. In your role as storytelling partners, how do you help form a narrative when it is sometimes just inherent in the work?

Likewise, some audience members engage very visually, while others benefit from the stories that help them understand or feel the artwork. We all learn and receive the world in different ways.

BARRY

I enjoy unpacking or describing connections between different works or ideas that an artist has. Because you are regularly engaged with them, you accumulate knowledge and find ways to convey that information to others when appropriate, be it through exhibitions or conversations. I appreciate language as a quest for accuracy—finding the right words and grammar to explain what was happening in the absence of the artist. While you can’t always offer the exact factual truth, your accumulated reflections can lead you to clarity over time.

For example, when I worked closely with James Capper, we had to identify terminology that best described his artistic practice, particularly the language of sculpture. You referred to it as kinetic sculpture, but we dismissed that term in favor of mobile sculpture because we felt "kinetic" had connotations of a different time. When I first met James and encountered his incredible practice, there was no one truly making sculpture like his, sitting at the intersection of sculpture-making and self-taught engineering.

These sculptures are not just ideas or dreams; they are real objects with specific purposes and applications. We needed an organizing structure to classify them, allowing people to understand James's evolving practice as he pursued his artistic goals.

In recent years, the sculpture has evolved beyond mobile sculpture and engineering to include elements of biomimicry. In our ongoing project in Kiev, humanitarian questions have also arisen. The reach of sculpture has always been broad, but my job was focused on describing it accurately and clearly, ensuring people understood what it was and what it wasn't.

With another artist, George Rouy, I've explored similar themes. Since 2017, we have discussed his concept of "the bleed," a place between bodily construction, deconstruction, and reconstruction, investigating the relationship of the body to itself, others, and the land we inhabit. He describes "the bleed" as the ultimate harmony in a painting that presents multiple ideas together. He has mentioned that in his last two works—the painting The Witness, currently on show at the Pompidou, and a painting called Land Sickness—he may have reached the culmination of his investigations into "the bleed."

Again, it’s not about language for language's sake; it’s about using the right words in the right sequence to describe what is happening and communicate that widely. The same is true when working with music, dance, or other artistic disciplines. Our role as administrators of these creations is to be accurate in our descriptions to others.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

I don't want to say that art has a responsibility to engage with social or political issues, but it is hard not to. As we navigate heavy times—with environmental crises, wars, and the growing disconnect among people—how do you see your role as a gallerist? I don't want to use the word responsibility, but we can’t turn our backs on these issues. How do we balance this with the pleasures of art as you choose stories, exhibitions, and projects to produce?

BARRY

I think when works come into your orbit that may not necessarily comment upon issues but instead illuminate or ask us to reflect on them, we should make them visible. I feel hopeful. I remember in 2008, just before the financial crisis, an exhibition we organized titled Optimism: The Art of Our Time.

It's strange timing. Every year, our thematic program drives our focus. This year, the theme is déjà vu, and next year it is euphoria. However, in 2020, pre-COVID, our theme was tragedy. We retained that theme, although it was somewhat suspended that year. When we reopened to the public—a challenging process—we organized some of the only live events with an audience that year. It became clear that people wanted to engage and sought out something meaningful through those experiences. In the following years, we shifted the themes to love, crisis, and communion.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

I think curators are a part of the artistic practice; I call them the invisible arts. They work behind the scenes as producers, making things happen. This role adds to what's out there in the world; it acknowledges that audiences may be waiting for certain expressions.

BARRY

We are organizing an exhibition of new work by Danny Fox, an artist from Coolmore, which we will present in October. In November, we will host an exhibition celebrating the work of Norman Hyams, who tragically passed away last year. Everyone here at the gallery was very close to him. It is quite poignant to realize that Norman will not create any more work beyond what he left behind, so we are just beginning the process of organizing that exhibition now.

I believe making and constructing in times of extreme destruction can offer a certain type of catharsis. If I reflect on my own life during challenging times, it can be difficult to see work as cathartic, but it is always present in one's endeavors—whatever they may be; support from friends and family can also help. There is a catharsis that can emerge from engaging in work.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

I think you're right. You described yourself as optimistic.

BARRY

I refuse to abandon hope, to be honest.