Giuliano Amedeo Tosi, born in 1992 in Bern, Switzerland, is an artist who has carved out a distinctive creative identity. Since 2020, he has been active on social media under the handle @giuliano_tosi, building an engaged international community around his work.

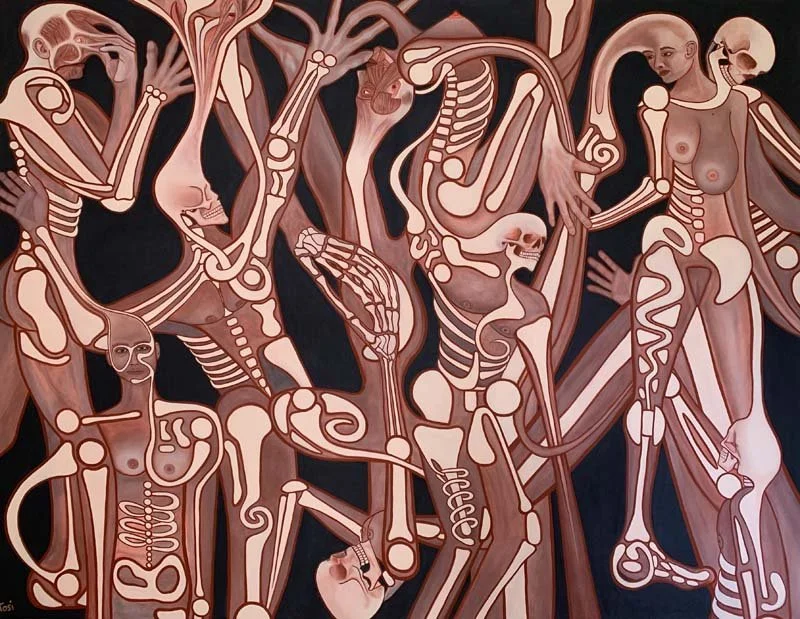

His art explores the fusion of the human form with natural elements —pushing boundaries with immersive and unfiltered expressions that challenge societal norms. His projects have sparked significant media attention and fostered meaningful conversations.

Currently, Tosi is evolving his style, shifting from figurative paintings to a multilayered organic approach that blends natural forms with bodily structures, creating a fresh and pioneering aesthetic. His influence extends far beyond Switzerland, resonating globally. His works have been showcased in exhibitions and publications across regions, including the USA, the United Arab Emirates, Nepal, Italy, and his native Switzerland, leaving a lasting impact on the international art scene. @giuliano_tosi

Where were you born and raised? How did it influence your art and your thinking about the world? I was born in Bern, Switzerland, and grew up in a quiet, rural suburb called Bolligen. The area is beautifully green and peaceful, but also quite conservative and affluent—a classic Swiss environment. My upbringing was shaped by a mix of contrasts: My father was an entrepreneur, my mother a former athlete. While there was little exposure to art at home, I was supported musically from a young age.

My childhood was marked by both care and conflict. My parents divorced when I was 15 after years of tension, which left me with a strong sense of emotional duality—love and anger often coexisted. Discussions at home were rarely constructive, and trust wasn’t something I grew up with easily. This complexity shaped a sensitivity in me that now flows directly into my artistic practice.

I vividly remember being introduced to Joan Miró in first grade—his work fascinated me. I started copying his paintings at home, and that moment sparked a deep curiosity for visual expression. Later, in elementary school, a teacher named Urs Nydegger introduced me to design and encouraged my interest. My uncle, Beat Drack, also left a strong impression: he was highly cultured, played Chopin beautifully, and introduced me to a refined way of thinking.

Despite these early sparks, I only began creating art in earnest in my early twenties. I visited museums alone, studied paintings by sketching them, and started painting on the floor of my tiny room in a shared apartment in Zurich. That’s where it all began. I’ve never stopped since.

While my formal training is minimal—just a couple of acrylic and figure drawing courses—I’ve taught myself most of what I know through practice, observation, and deep personal exploration. Living in places like Zurich and later in Asti, Italy, also widened my perspective and helped me find my own visual language.

Was there a particular experience or realization that confirmed you wanted to become an artist, and how did that choice shape your identity and direction? The turning point came after a painful breakup with my first great love, Ellen. I was overwhelmed by grief and emotion, and in the middle of that storm, I began painting what would become my first major work: Organism Humanity. I created it over two months in my living room in Zurich, often painting through tears. That process—transforming pain into form—was a revelation. When the piece was finished, I knew: this is it. This is what I want to dedicate my life to.

What truly captivated me from the beginning was the challenge. Painting demands creativity, technique, structure, and intense focus. It felt limitless—more so than music, which I also explored. I realized I could do this for the rest of my life without ever getting bored. That’s rare for me—boredom sets in quickly otherwise.

Today, art is my language. It’s how I process and communicate emotions, society, criticism, politics, beauty, and innovation. It’s a fusion of handicraft and reflection—of aesthetic and intellectual research. Art mirrors life to me, and in many ways, it feels like my life’s purpose. My first love.

Depending on the project, my work varies in depth—from deeply conceptual to purely visual. But in the end, I’ve succeeded when I move something within the viewer. If a piece resonates, provokes, or simply stops someone for a moment, then it has done its job.

What does your typical day in the studio look like? Walk us through your studio and your most used materials and tools. I currently work between two studios. One is in my duplex apartment in the heart of Bern, where I focus on smaller formats. The other is in Asti, Italy—in a converted space that used to be a cow stable, part of an old rural farmhouse. I work exclusively alone. I can’t have other people around while I create—at most, I’ll take a phone call during more logistical or mechanical tasks.

My studio, when I'm working, is absolute chaos—Francis Bacon would probably nod in approval. But unlike him, I clean everything up once a work is finished. I paint one piece at a time, never multiple projects simultaneously. That way, each work has a full cycle: chaos, completion, and then the ritual of cleaning—so I can fully reset and direct my energy into the next idea.

In Asti, I heat the studio in winter with a wood-burning fireplace. It's a quiet, isolated space—deeply peaceful. I often paint for 5 to 8 hours straight, with short breaks to eat or drink coffee. Sometimes I work with loud music, other times for hours in complete silence. My routine is fluid—I resist rigid rituals, except for 2–3 coffees a day. I like to stay experimental. When I feel comfortable, the work flows naturally.

I mostly use acrylics on canvas, working with brushes, trowels, charcoal, sponges, staples—and occasionally plaster. My tools vary depending on the conceptual or textural needs of each piece.

And one last detail: because my space is so isolated, I often work naked or in my underwear. That’s when I feel freest—completely unfiltered, physically and mentally. It’s just me, the space, and the work.

You’ve just completed a solo exhibition—what was that experience like, and what themes or ideas drove the exhibition? Yes, I just completed my latest solo exhibition Morph.X – Transcendence in Crisis, currently on view at Galerie Alte Brennerei in Switzerland. The exhibition explores the transformation of the human figure in times of ecological collapse, digital alienation, and the rise of artificial intelligence. Rather than dissolving, the body in my work mutates—becoming fluid, porous, and interwoven with its environment. Morph.X reflects a shift in my practice toward a more immersive, sensorial, and hybrid visual language that dissolves the boundaries between subject and space, humanity and nature.

At the same time, I’m preparing for my participation in Fresh Art 2025 at Apart Galerie in Solothurn. One of my newest pieces is a large-scale nature painting (200 x 160 cm), inspired by a place that has deeply shaped me since childhood: St. Peter's Island on Lake Biel. It’s a personal and emotional return to a source of wonder and solitude that has stayed with me for decades.

The core themes currently driving my work are human transformation, ecological consciousness, and the tension between transcendence and collapse. I’m deeply interested in how the human experience is reshaped by climate anxiety, AI, and social fragmentation. My art doesn’t offer answers—it creates spaces of reflection, vulnerability, and expansion.

Some projects are conceptually heavy, others more visual. But ultimately, I always aim to shift something in the viewer, even if subtly. If my work opens a new space of feeling or thought, it has served its purpose.

What do you hope people feel when they experience your art? What are you trying to express? I hope my work encourages people to open their minds—perhaps even to step beyond their personal boundaries, their fears, their familiar ways of thinking. Ideally, I want the viewer to be moved both emotionally and intellectually. And yes, beauty matters to me too. If someone finds something beautiful in my work, that resonance is just as valid and powerful as a conceptual reflection.

My goal is to create layered experiences—emotional, critical, aesthetic. I want to trigger thought, invite emotion, and, when possible, initiate dialogue. Some works speak quietly, others provoke. But all are meant to connect, to shift something inside.

As for what I express—there’s no single message. My practice is intentionally diverse, often unfolding in series of up to 30 pieces before moving on to a new theme or visual world. Life itself is plural and evolving, and my art reflects that. Reducing myself to one idea would feel dishonest—it would go against everything that drives me creatively.

Which artists, past or present, would you like to meet? And why? I’d love to meet Egon Schiele, Francis Bacon, Lucian Freud, Ferdinand Hodler, Picasso, Rubens, and even Da Vinci. Not just for their artistic brilliance, but because they were all larger-than-life figures—intensely driven, complex, and relentlessly committed to their craft. Their biographies are as fascinating as their works, and I’d love nothing more than to spend a day as a ghost in their studios, quietly watching how they lived, thought, and created.

Each of them mastered their medium in such a unique way. I’m fascinated by their different forms of obsession: Schiele’s raw sensitivity, Bacon’s emotional brutality, Freud’s psychological depth, Hodler’s symbolic reduction, Rubens’ lush vitality. Even Da Vinci—with his scientific curiosity—is a world of his own.

And then... there’s Jeff Koons. I'd like to meet him just so I could honestly tell him that I find his work really, truly bad. But in a friendly way.

Do you draw inspiration from music, art, or other disciplines? I’m deeply connected to music—I play guitar and drums myself, and I’ve played in bands from time to time. But interestingly, I don’t really draw direct inspiration from it when I paint. For me, it’s more of a parallel channel—something I do intensely for a while, then step away from once it starts to bore me. I get bored easily if something becomes too repetitive or predictable.

What truly inspires me is visual art itself. Going to museums, seeing exhibitions, discovering new works or revisiting old ones—that’s what fuels me. The act of seeing, feeling, and studying other artists’ work is what truly triggers my own ideas.

As for other disciplines—it could be anything. I don’t limit myself. Inspiration can come from a walk, a texture, a conversation, or something I overhear in the street. But if I’m honest—music is more of a companion than a source. The real spark usually comes from art itself.

A great thing about living in my city/town is…: The atmosphere in Bern is something truly special—calm, soulful, and quietly inspiring. In summer, nothing beats a swim in the Aare River, drifting through the old town as the cathedral towers above you.

There’s a creative energy here that’s hard to explain. Many of Switzerland’s best artists and musicians come from Bern—maybe there’s some kind of secret in the water.

It’s a hidden gem. People often think Zurich is the capital and skip Bern entirely. I always tell them: That’s a mistake. Come visit—you’ll understand.

What’s a project that made you rethink your approach to art, and what was it like to work through it? One of the most challenging and meaningful projects I’ve ever created was Schwarze Berge (“Black Mountains”)—a stark visual reflection on the climate crisis. The project imagined a near future in which the glaciers have vanished, the mountains are bare and black, and even Bern’s iconic river, the Aare, has dried up. It was a dark vision—but a necessary one.

I painted 20 works for the exhibition. Just two weeks before the opening, all of them were destroyed in transit. That moment was devastating. But I knew the message of the show was too important to abandon. So I started again—working day and night to repaint the entire series from scratch.

One centerpiece of the exhibition was a 700-kilogram sandstone boulder placed in an oil pan. Over time, the stone absorbed the liquid, like a dying glacier pulling in the last of its surroundings. The installation was visceral, heavy, and symbolic.

The show opened at a crucial moment: during Switzerland’s national vote on the Glacier Initiative. Politicians gave speeches at the opening, and leading climate scientist Thomas Stocker delivered a powerful talk. The project brought together science, politics, art, and activism—and was featured on national television and in major newspapers.

It was exhausting, emotional, and logistically intense. But the result was deeply rewarding. Looking back, Schwarze Berge marked an important turning point in my practice. It underscored my belief that art has a role to play not just aesthetically, but socially and politically. It was a moment where everything I care about came together.

Who were the important teachers/mentors/collaborators in your life? I’ve never had a formal mentor in the arts. I’m entirely self-taught—and in that sense, I consider myself my own toughest teacher. I grow through my own challenges, through each new exhibition, and through pushing my own limits. Of course, countless artists have inspired me along the way, but too many to name.

That said, there are people who have shaped me profoundly. One of them is my childhood friend Carlo—we’ve known each other since we were in diapers. As a teenager and young adult, I looked up to him intellectually, and he influenced the way I think, reflect, and question the world around me. His presence in my life was a kind of silent mentorship.

While I haven’t collaborated with other artists in a traditional sense, I’ve grown a great deal through working with curators, organizers, and gallerists—people who challenged me, expanded my perspective, and helped me sharpen both my practice and my voice. For me, growth comes through confrontation—with ideas, with limitations, and sometimes with failure.

Sustainability in the art world is an important issue. Can you share a memory or reflection about the beauty and wonder of the natural world? Does being in nature inspire your art or your process? Nature has always grounded and inspired me—visually, emotionally, and spiritually. Two places have shaped that connection deeply: the deep blue of the sea in Calabria, where my mother was born, and the lush, vibrant green of St. Peter’s Island in Switzerland, a place I’ve returned to since childhood. These landscapes speak to something primal in me—the human being at their most natural, even naked. That state of pure presence is a recurring theme and passion in my work.

Today, nature is absolutely essential to my creative process. When I’m in natural surroundings, I feel peace, freedom, and clarity. With fewer worries in mind, I become more open, intuitive, and focused—more creative. Nature strips everything back to what really matters.

Many of my works integrate that connection, not only in subject but in mood and material. Sustainability, for me, starts with attentiveness—with remembering that we are not separate from nature, but part of it. Art can be a reminder of that truth.

AI is rapidly changing the way we construe art and creativity. What concerns or hopes do you have about AI in the arts? What is your own relationship with technology as a creative tool? I find AI absolutely fascinating. I read about it constantly and use it daily—especially for research and to streamline parts of my workflow, like now, while answering these questions. As a tool, it’s incredibly powerful. But when it comes to art, something essential is lost: the inner, human process of creation—the flaws, the effort, the tactile reality of materials. The technique, the soul, the struggle—that’s what makes human art so meaningful to me.

As a painter, I work with brush and canvas. Each piece I make is singular, imperfect, and mine. I’m not a robot. And I believe that uniqueness—our physical, emotional, and psychological imprint—is something AI can never fully replicate. That’s not a criticism of the technology, but a reminder of what sets us apart.

I don’t think AI in art is something to fear—it’s here, and it’s not going away. It will likely surpass us in many ways. But that makes the handmade, the personal, and the imperfect even more precious. In the future, I believe hand-crafted human work will become even more valued—both culturally and economically—because it carries a kind of authenticity that no algorithm can simulate.

I'm curious to see how we will coexist with AI in the coming years. The question is not whether it will change us—it already has—but how we, as artists and thinkers, respond.

Exploring ideas, art and the creative process connects me to… Life itself.