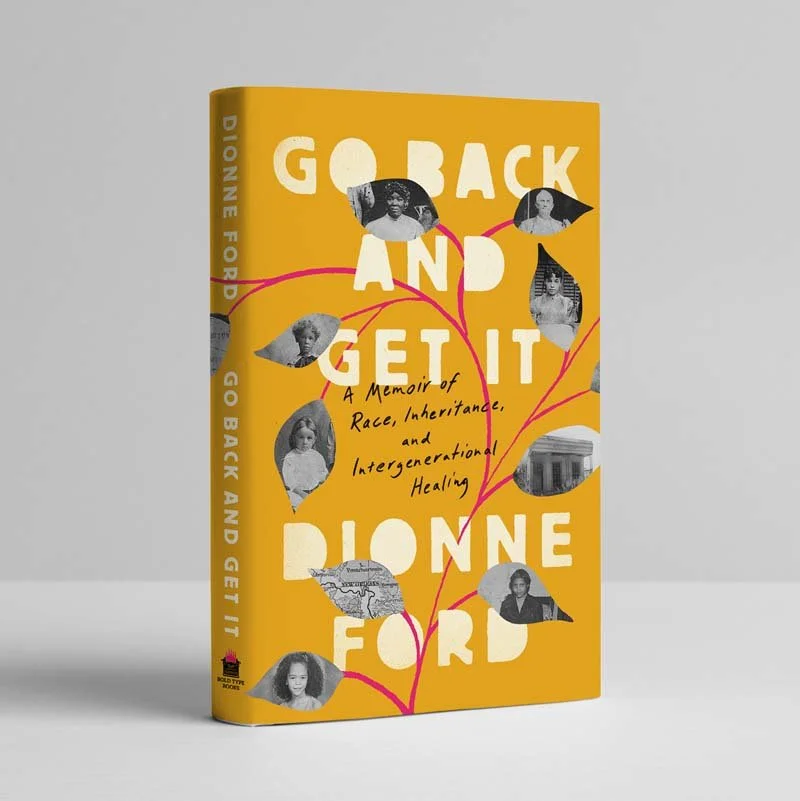

Dionne Ford is author of Go Back and Get It, a 2024 finalist for the Hurston Wright Foundation Legacy Award and co-editor of the anthology Slavery's Descendants. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, The Virginia Quarterly Review, LitHub, The Boston Globe, and Ebony, among other publications and has won awards from the National Endowment for the Arts, the National Association of Black Journalists, and the Newswomen's Club of New York. She teaches creative writing as an adjunct at Fordham University and is editor of Lynchings in the North, an initiative of NYU’s journalism program. @dionnelford

How do you think your early life in Maine and New Jersey helped cultivate the kind of writer you became? I was born in Maine, the whitest state in the country, and raised in what abolitionists called the slave state of the North, New Jersey—the only state in the Union that never voted for Lincoln and the last to abolish slavery. New Jersey is one of the most diverse states demographically, but it’s also highly segregated. All of these tensions and dichotomies have shaped me and influenced my writing, which is always circling around how a place affects and motivates people's actions and beliefs.

What kind of reader were you as a child? What books made you fall in love with reading? The first book that captivated me as a child was the Bible, and the last book, Revelation, in particular. It was both engrossing and terrifying, and I just couldn't look away. Are You There God? It's Me, Margaret also made a huge impression on me because it was informative and engaging around a topic that I needed to talk about but couldn't. Anne Rice's vampire series, Toni Morrison's Tar Baby, Alice Walker's The Color Purple, and Maya Angelou's All God's Children Need Walking Shoes made me fall in love with both reading and writing. I felt connected to the world when I read them in a way that I did not in my actual life, and I wanted to emulate that.

What kinds of routines structure a typical day of writing? I typically write first thing in the morning before the day sweeps me away. When a piece of writing is new, it usually grabs me and keeps me engaged, so I let it take me where it wants to go for as long as my schedule will allow. I find the editing process more difficult, so I am more regimented about that, scheduling blocks of time during the day for that purpose. The only time I ever outlined a story was when I was taking a workshop with Colson Whitehead, who told our class that he always starts with an outline. That's worked out pretty well for him, so I am determined to try it next time.

Tell us about the creative process behind your most well-known work or your current writing project. My memoir Go Back And Get was prompted by a conversation with my grandfather when I was 12 and then a comment by my daughter almost 25 years later. I wanted to write about my family's history through the lens of the family I'd created, so the process was very research-intensive. I decided early on to keep a research journal, documenting what information I was looking for and the process of finding it and what it evoked in me. That approach kept my current life threaded into the past that I was unveiling and kept that research tethered for me.

You’ve mentioned keeping a journal—what kind of entries fill those pages? I've kept a journal since I was seven years old, and my parents gave me a diary with a lock and key. I write in it daily about my thoughts, aspirations, and fears, as well as whatever guidance I receive from the Divine, which for me is my Ancestors. I also save ephemera from literary events, concerts, exhibits, or meaningful gatherings in my journals.

Which writer, living or dead, would you most like to have dinner with? This is a tough question, but I think I would like to have dinner with Zora Neale Hurston.

Do you draw inspiration from music, art, or other disciplines? Visual art and architecture are a huge inspiration for me, perhaps because they are not a written medium and they give my writing mind a chance to breathe. I also love music. I usually make a playlist for my longer writing projects, and depending on where I am at in my writing, I listen either before or while I'm working.

AI and technology are changing the ways we write and receive stories. What are your reflections on AI, and why is it important that humans remain at the center of the creative process? What is always at the center of any art, to me, is an experience. Until AI can have its own experience of a sunrise, or holding a child's hand, or helping a stranger navigate a tricky crosswalk, it will not replace us. My hope is that AI is contained to its best use - as a tool to aid creativity akin to a typewriter or computer.

Tell us about some books you've recently enjoyed and your favorite books and writers of all time. Recently, I've really enjoyed Craft: Stories I Wrote for the Devil, Neruda on the Park, Coleman Hill, In Open Contempt, Hot Air, The Secret Life of Church Ladies. My favorite books of all time are Salvage the Bones, How to Slowly Kill Yourself and Others In America, My Brilliant Friend, The Friend, Luster, Their Eyes Were Watching God, The Bluest Eye, Giovanni's Room. My favorite playwrights include August Wilson and Suzan-Lori Parks.

Exploring literature, the arts, and the creative process connects me to… The depth and breadth of humanity, which is also like connecting me to the Divine.