John J. O'Connor, born in Westfield, MA, received his MFA in painting and an MS in Art History from Pratt Institute. He was awarded a 2023 Guggenheim Fellowship and has attended residencies such as MacDowell, Skowhegan, the Vermont Studio Center, the Cold Spring Harbor Science Center, and Civitai AI. A recipient of grants from NYFA, the Pollock-Krasner Foundation, and the Marie Walsh Sharpe Foundation, his work has been exhibited nationally and internationally, and has been reviewed in publications such as The New York Times, Artforum, Bomb Magazine, The Brooklyn Rail, and Art in America. John’s work is held in the collections of the Museum of Modern Art, Whitney Museum of American Art, Weatherspoon Museum, Hood Museum, and the New Museum, among others. He teaches at and co-chairs the Studio Arts program at Sarah Lawrence College and collaborates with the author Rick Moody in a project called Superspreaders, and is a member of the experimental art and technology collective NonCoreProjector. @jjayosea

Reflecting on your childhood in Massachusetts, how did it mold your approach to art? I was born and raised in Westfield, Massachusetts, nicknamed the “Whip City.” In the 19th century, it was the world’s leading center for manufacturing whips for horse-drawn carriages and wagons. For me, though, it was a small, quiet town, and my family was all over. What shaped me most was the amount of free time I had as a kid, especially in the summers, to simply do nothing. My brother, our friends, and I spent our days roaming around, daydreaming, inventing games, and causing trouble in the neighborhood. That openness and use of whatever materials were on hand had a huge impact on my thinking and making. We weren’t making art, but it was deeply creative and free.

As a teenager and through college, I also worked as a hospital dishwasher and cook. The rigid structure and lengthy process of food preparation (the menu collation, ordering, shelving, pre-prep, cooking for large numbers of ill people, and then cleaning and readying the kitchen to do it all again) taught me how systems work, what is visible or hidden, and how that relates to a final presentation or image. There was something about the “ghost in the machine” that stayed with me. I also loved the chaos of the kitchen and the intense emotional connections between all of us. That was an interesting contrast to the rigidity of the systems we worked within.

When did you first fall in love with art and realize you wanted to be an artist? For you, what is the importance of the arts? I don’t think there was one defining moment. I always loved to draw as a kid and drew a lot as a means of breaking from the intense social demands of school. In college, I bounced between psychology and math before taking a design class that I loved. It was the only class I put true energy into, which led me to switch to become an art major. After undergrad, while still cooking and doing small graphic design jobs, I spent two weeks at the Vermont Studio Center. Being surrounded by creative people, writers, and artists from different generations showed me what a creative life could be like. I thrived there and realized this was what I wanted to do and who I wanted to be.

The arts explore ideas before other disciplines do. Art can suggest new realities or alternative directions that other fields later follow. It also synthesizes diverse systems and ideas in ways that have no purely practical function, which makes it both novel and groundbreaking - pure novelty. That freedom to create and explore without purpose is so vital.

What does your typical day in the studio look like? Walk us through your studio and your most used materials and tools. I love a full studio day. I usually start around 8:30 with my dog Luna on the couch beside me. I spend about half an hour or so experimenting with generative computer programming, which feels like stretching before exercise because it opens up my thinking for when I start drawing. I then work on smaller drawings, often many at once, until lunch. The rest of the day, until around 6pm, is spent on large-scale works. I listen to music, podcasts, or audiobooks, depending on whether I’m solving a problem or filling in patterns. Sometimes I return to the studio late at night, from 10 to midnight, whenever I can.

My studio is in my house and was an office for the previous homeowner. I use my computer, and I have about 1,000 colored and graphite pencils. There’s a flat file with finished and unfinished works, racks with paint, photo equipment, and sculpture materials. But pencils, colored and graphite, are my main tools, along with lots of sharpeners and erasers.

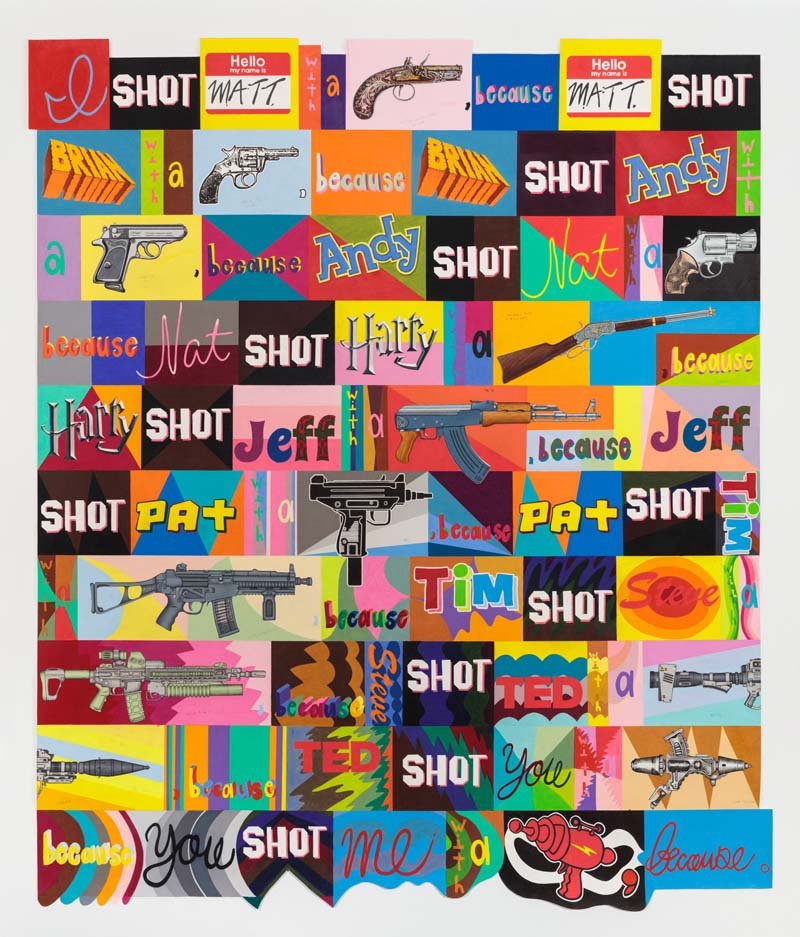

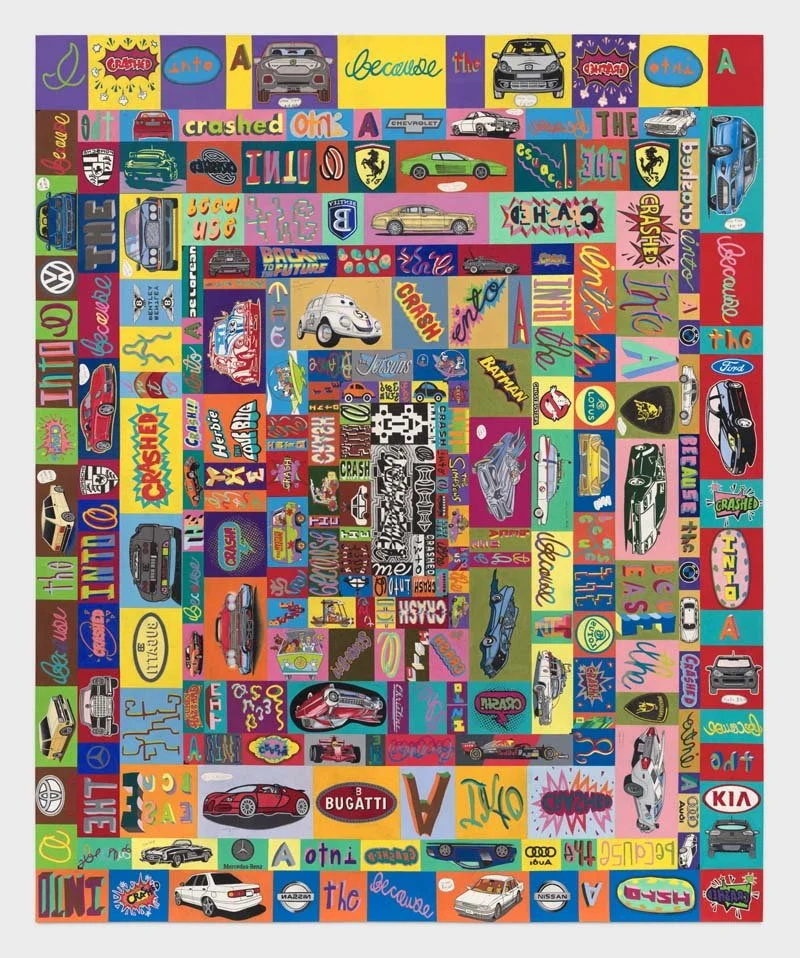

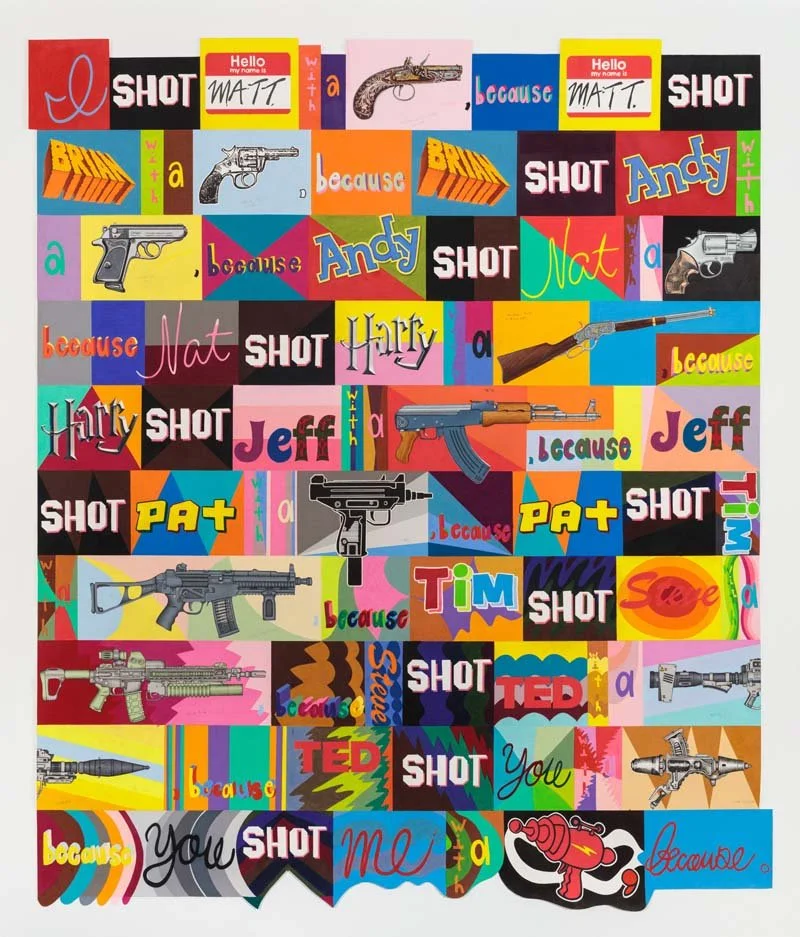

What projects are you at work on at the moment? And what themes or ideas are currently driving your work? I’m collaborating on ongoing politically-based multimedia projects with the writer Rick Moody, and developing a new curatorial idea/project with my friend Philip Glahn. NonCoreProjector is working on new ideas, including one for a classic 1950s drive-in (hopefully). I’m also creating new large-scale drawings that merge probabilistic models like Markov Chains with historical, language-based predictions of the future. In these, I’m exploring the human drive to foresee and control the unpredictable.

What do you hope people feel when they experience your art? What are you trying to express? Curiosity, unease, laughter, and a sense of something slipping between recognizability and abstraction. I hope viewers first engage with the surface and aesthetics, then start decoding and interpreting, like solving a puzzle or thinking about song lyrics after getting into the music and sound. I hope the formal qualities of my works open up to ideas that move in myriad directions away from the artwork, connecting across time, disciplines, and place.

Which artists, past or present, would you like to meet? And why? Alfred Jensen. He’s been a huge influence on me.

Do you draw inspiration from music, art, or other disciplines? Many disciplines shape my work. I’m drawn to overlaps and contradictions between science, math, anthropology, media, politics, linguistics, and psychology, to name a few! Music was also a big influence. Growing up, I listened to and even played grunge. I think, even subconsciously, that grunge's oppositional thrust - soft-hard-soft patterns & rhythm - shaped how I think visually. Alfred Jensen also worked with oppositions, blending spiritual and scientific ideas, and drew on Goethe’s color theories, which were also based on contrast.

A great thing about living in New York is… I’m close to New York City but also surrounded by nature, a balance I love.

Can you describe a project that challenged you creatively or emotionally—and how you worked through it? My first collaboration with NonCoreProjector was challenging in so many ways. I worked with other visual artists, sound artists, programmers, and AI scientists. The project, "Verbolect," relied on real-time programming, projection, sound, and chatbot data. It ran 24/7 for a month. Technical issues were constant, and when something failed, the piece just stopped until we fixed it. Relying on unpredictable and volatile information was stressful, but also thrilling. That unpredictability made the work come alive.

Tell us about important teachers/mentors/collaborators in your life. I had a college drawing teacher who rarely “taught” in the traditional sense. He gave us assignments and then worked on his own abstract drawings, which were essentially abstract studies in light and dark - they had a feeling of how Seurat's drawings lacked clear edges. Watching him work in this way and also in an ongoing series taught me the value of iteration. Another teacher at the time, Nathan Margalitte, was incredibly supportive. When I took his Painting II class and showed him an independent painting I was working on, he encouraged me to continue developing that series for the rest of the semester and allowed me to focus on my own work instead of the regular assignments. We then discussed the work each week on one. It was so exciting. His belief in me gave me confidence.

Sustainability in the art world is an important issue. Can you share a memory or reflection about the beauty and wonder of the natural world? Does being in nature inspire your art or your process? Nature inspires me, especially emergent systems, how insects act individually but form collectives, or how birds create complex flying patterns. I’m fascinated by birds and their language. Bird calls may sound abstract, but they have intention and structure. Listening closely reveals patterns. I hope my art unfolds in a similar way, revealing subtleties over time.

AI is changing everything - the way we see the world, creativity, art, our ideas of beauty and the way we communicate with each other and our imaginations. What are your reflections about AI and technology? What is the importance of human art and handmade creative works over industrialized creative practices? I use AI in collaborative projects and treat it as a tool, like any other. I don’t use it to generate imagery, but for gathering and organizing data or source material. I’m fascinated by the tension between the handmade and the technological. When I draw something that looks digital or mass-produced, I like how the unique, hand-drawn version feels uncanny. It is both a replica and a singular, one-of-a-kind object.

Exploring ideas, art and the creative process connects me to…everything I can think of.