Alessandro Keegan is a visual artist working in oil paint and mixed media, as well as a writer and art history professor. He has an MFA in painting and drawing from The School of the Art Institute of Chicago and a MA in art history from Brooklyn College. Keegan, who has training as a gemologist, worked at the Gemological Institute of America in New York until 2012, while completing his education. He currently lives and works in the Hudson Valley town of Walden, New York.

Keegan’s paintings have been exhibited in New York, London, Milan, Berlin, Barcelona, Hong Kong, Seoul and many other cities around the world.

Writings about his work have appeared in Artsy, ArtMaze Magazine, Artforum, Cultured Magazine, Elephant Magazine, Masthead Magazine, Helvete, J’ai Froid and the 2023 book “New Surrealism: The Uncanny in Contemporary Painting” published by Phaidon International. @alessandro_keegan

Growing up in the state of New York, what aspects of that environment have permeated your artwork? I was born in the Hudson Valley region of New York and raised in the town of Nyack, where art as a way of life was ever-present. The Hudson Valley is best known for being the birthplace of the Hudson River School painters of the 19th century, who were drawn to the area's majestic light, landscapes, and mountain wilderness. The area was home to 20th-century artists like Edward Hopper, Kurt Seligmann, Tony Oursler, Joseph Cornell, and Richard Pousette-Dart, as well as writers like Carson McCullers and Toni Morrison. In addition to the artistic community found there, the Hudson Valley is a very weird, eccentric place. It was, and still is today, an epicenter of Spiritualism, UFO activity, haunted houses, and other kinds of paranormal mysteries. There are a number of small, alternative religious communities there, or what some would call "cults", so it shouldn't be a surprise that I was exposed to a lot of non-mainstream spiritual thinking when I was growing up. I also think that the Hudson Valley, which is just on the boundary between the more rural, open country of upstate New York and the dense, bustling urban life of New York City, impressed upon me the power of nature, even after I moved to Brooklyn in my early twenties.

When did you first fall in love with art and realize you wanted to be an artist? For you, what is the importance of the arts? As a child, I dreamed of being a scientist. I did eventually get a degree in gemology from the Gemological Institute of America, and I worked as a gemologist for a few years, but I was never really passionate about science as a job. I was more curious about the natural world because its very existence has always seemed miraculous to me. Art became my passion just as I entered high school, it was a means of survival during a difficult and alienating time in my life, a time when I was using drugs quite a lot, and I was living with my mother and my grandmother, who was also very sick. Apart from being an outlet for the mental anguish I felt during that time, art also became a doorway through which I could pass into any area of interest or curiosity, whether that be technology, biology, music, history, or ancient esoteric thought. During my teenage years, I also began getting very interested in occult thought, beginning with some of the obvious writers, like Aleister Crowley, Robert Anton Wilson, and Phil Hine, and then later delving deeper into alchemy, John Dee, and the Corpus Hermeticum. Later in life, I delved even deeper than these writers, into eastern religious practices of Qigong and so forth, though I don't follow any path, tradition, or ceremonial magick practice today.

Art isn't just therapy or play, as some might see it, nor is it decoration or a commodity object. Art is an act of affirming our reality, and by extension, it is something capable of transforming reality. Art blends so easily with our day-to-day life that we rarely notice how art and the visions of artists act upon every aspect of our culture and being. Sadly, for most people, art seems to be an elite, inaccessible object that hangs in a gallery or museum, and oftentimes it is viewed with suspicion and confusion. This is the reason why arts education is so important, even though some may dismiss the field as irrelevant and childish. When we appreciate art properly, we see that it is more than just a fetish object for the market, or a frivolous topic of academic discussion; art is the fabric of reality, it composes the ocean of life in which we swim.

What does your typical day in the studio look like? Walk us through your studio and your most used materials and tools. I am a full-time college professor and the father of a two-year-old daughter, so my studio work must always be balanced with these responsibilities. I set aside special days to work in the studio non-stop for six to eight hours. It helps that my studio is in my house, a large Victorian home in the Hudson Valley. If I am going to put in a long day or two in the studio, it is crucial to prepare in advance. At night, after we put our daughter to bed, I clean all my brushes and palettes and make sure everything in my studio is ready for the next day.

I wake up at 5 AM, I exercise, meditate, wake up my daughter at 7 AM, and make her breakfast. By 8:30, she's in daycare, and I am in the studio. I try to have a plan for the day, two or three objectives, and parts of paintings that I must complete before 3 PM. If I have a good day, I will maybe complete two of these objectives; rarely do I get everything done. I also work on multiple paintings at once. I currently have four in process. This allows me to always have something to work on while I am waiting for the other paintings to dry. My paintings are oil paintings and made in layers, so there are certain parts that can only be worked on when the surface has completely dried. I used linseed oil with a little Liquin, a rapid drying medium, but it still takes about twenty-four hours for the surface to be dry enough to paint over.

At 3 or 4 PM, typically, I stop and clean up and then go to pick up my daughter at daycare. I bring her home, make dinner before my wife comes home, and then I get ready for the next day.

As I get older, I realize exercise and meditation are important to keeping up the relentless pace of my work schedule. Meditation is also an important component of my work, because it is through that practice that I gain access to my other self, a kind of external mind that talks to me and shows me visions of the paintings I am going to make. To some people, when I mention hearing voices or seeing visions in my mind, this seems very eccentric. I think that anyone can tap into another consciousness and communicate with it if they want; you just have to take a few minutes out of the day to quiet your mind.

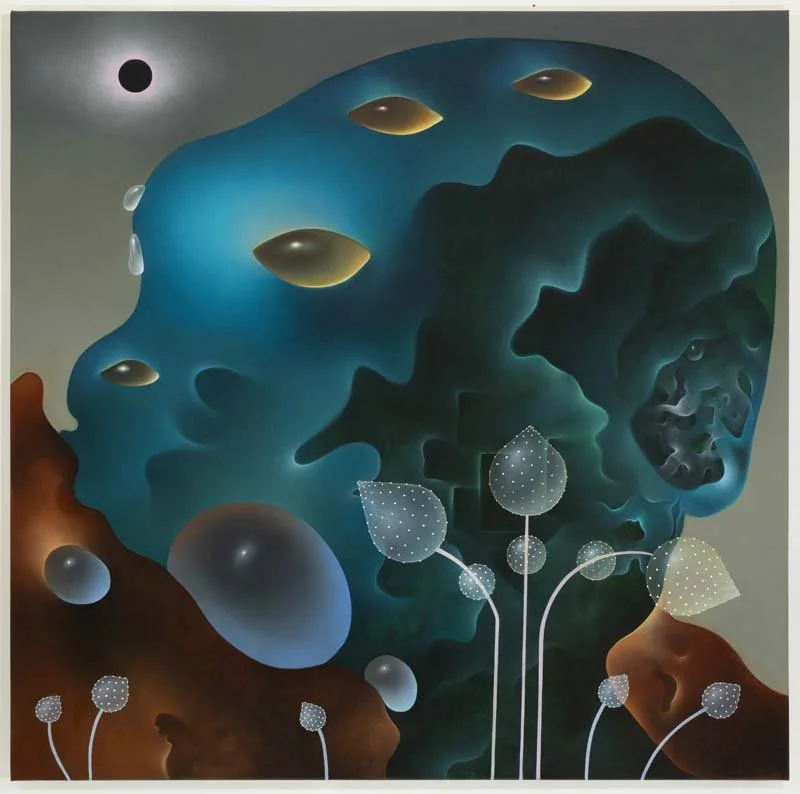

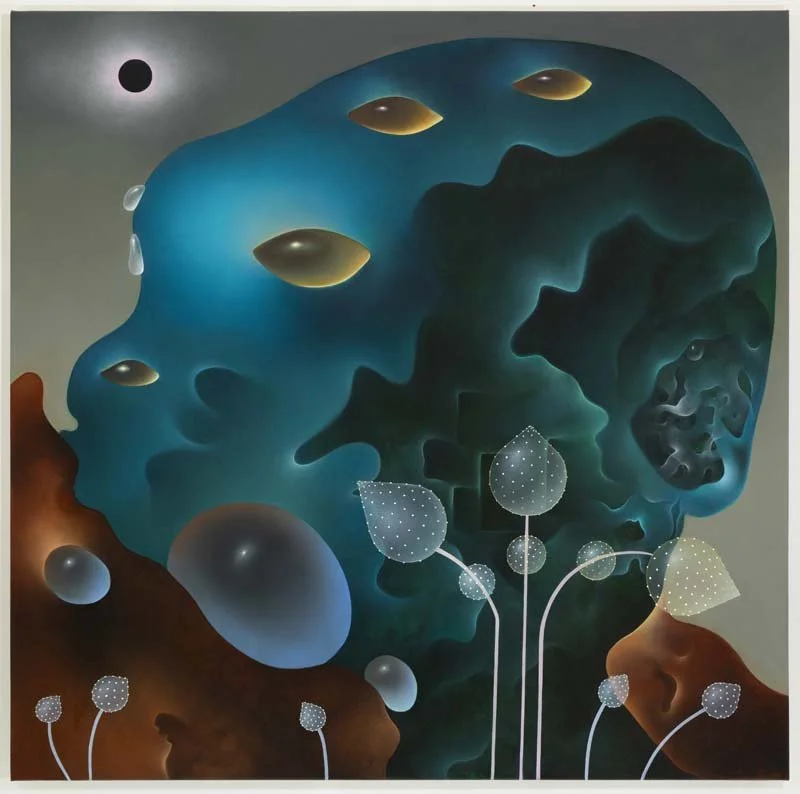

What projects are you at work on at the moment? And what themes or ideas are currently driving your work? The most recent paintings are built up in transparent layers or oil painting over a dark, textured ground made with mixed media and oil. Even when I am developing a form that has a dimensional quality and might suggest a body, a plant, an alien face, or a fungus, there is still a trace of the textured ground beneath the surface. I feel these works are most successful when the representational elements of figure and space still seem ambiguous. This new work is what I refer to as "Chthonic" or of the underworld. Chthonic gods, in the ancient world, were those that lived in the depths below Hades. For me, the Chthonic paintings are connected to nature, to the earth, and to the forces of chaos that technology and society seek to subjugate.

What do you hope people feel when they experience your art? What are you trying to express? Some people may not immediately associate my paintings with Romanticism, but I am a Romantic painter in the truest sense. Blake, Turner, and Caspar David Friedrich were exploring the idea of the "sublime" in the sense that the sublime is an experience not entirely of beauty, but of something awe-inspiring and dreadful.

Some may only associate the sublime in our modern age with creations that are grand in scale, like a giant, steel Richard Serra sculpture, but I think that what really makes a work sublime is its ability to reveal a clear vision and still retain its mystery. Serra's sculpture certainly does this, but small, intimate paintings and drawings can do this as well, like the quiet fantasy paintings of Remedios Varo.

I love to work on a large scale and make a world that you can get lost in, but the sublime can also be communicated by a more modest, scaled-down work as well. The magic is in creating a painting that seems clear on the surface but retains a deeper mystery and ambiguity that can never be unlocked. That is really where the sublime is located, in the unrevealed secret at the heart of an artwork.

Which artists, past or present, would you like to meet? And why? I have been fortunate to have met or spoken with many of the artists, writers, and musicians who have had an influence on me, though I really wish I could have met David Lynch while he was still with us. Aside from being a great artist, he seemed like a pretty cool guy.

If I were to dig into the past, I would say getting a chance to meet William Blake would be wild. He was a great artist and poet, unlike any other in his time, and was also a deep, esoteric thinker who held perspectives on art and history that broke from the status quo.

Do you draw inspiration from music, art, or other disciplines? My paintings have probably been shaped by music and literature more than other paintings. From an early age, I was drawn to music and writing that you had to dig for; artists that were forbidden, subcultural, or otherwise indigestible to the mainstream. In music, I was most drawn to bands like Throbbing Gristle, Coil, Current 93, Les Rallizes Dénudés, Nurse with Wound, Suicide, The Birthday Party, Factrix, SPK, and so forth. I still listen to music in this vein. However, when painting in my studio, I am probably more inclined to listen to some very chill ambient or electronic music in the background, like Loscil, Thomas Köner, or, recently, the Marek Zebrowski and David Lynch collaboration titled "Polish Night Music" has been on heavy rotation while I work in the studio.

There are many writers who have deeply affected me, but most of all, I have been inspired by Surrealists, Symbolists, and the various Decadents and Aesthetes of the late 19th century. Charles Baudelaire, Comte de Lautréamont, Joyce Mansour, Michel Leiris, Joris-Karl Huysmans, Mina Loy, and many others I would include among my favorites.

A great thing about living in Brooklyn is… I lived in Brooklyn for sixteen years, and just four years ago I moved to the country with my wife, and we had our daughter a couple of years later. So, I have lived a good part of my life in the city, and now I am in a more rural area. But I still take the train into the city twice a week to teach classes, so I still feel very connected to NYC.

I currently live in a small town in the Hudson Valley, and the great thing about living there is that it is quiet and affordable. I am able to live in a large house with a studio that is much bigger than what I could afford in Brooklyn. Having a daughter, it's also nice that I have a big front and back yard for her to run around in. At night, if I'm up late, I can go out on the porch and sit for an hour and not see a single human walk by. There is something relaxing about that.

What I miss about the city, however, is the culture, the art, and music that is always happening everywhere, and corner delis that are open all night, where you can go and get coffee at 4 AM if you ran out. Unfortunately, where I live now, everything is closed by 8 PM, and the closest place you might see a cool band play is over an hour's drive away.

Can you describe a project that challenged you creatively or emotionally—and how you worked through it? Probably the paintings that I am undertaking now seem the most challenging. These works came after an intentional shift in style about two years ago. For some time, I had been making very minimal compositions based on geometric drawings, but the geometry no longer felt relevant or impactful to me. I needed to bring an element of chaos, nature, and darkness back into the work to restore some balance that the spirit of my paintings felt like they were lacking. I think some galleries were dismayed by this, because my minimal, geometric, brightly colored works were actually selling quite well. Sometimes, if you're an artist listening to the inner voice, you just have to make decisions for the sake of your work and not based on what is selling or even what other people want you to do. The new work, which I have described as having a "Chthonic" spirit in it, was a little all over the place for the first year. Some were totally abstract, some looked like landscapes. I feel it is only now that I have started to rein in what these forms should look like. They definitely have alienated some people who preferred the work I was making four or five years ago.

It's hard to do something really different. The art market doesn't reward originality, sadly. It is much easier and more profitable to make a quick imitation of whatever is popular, and make it colorful, bland, and inoffensive, like decorative hotel art. As antithetical to real art as this may seem, that kind of strategizing and appealing to broad, simple tastes is the easiest way to make money as a painter.

In saying this, I don't look down on people who just want to make pretty paintings and get paid. I like making money too. I have had collectors ask me to make a scaled-up version of a smaller work, or they ask me to make a copy of one of my older paintings using certain colors they like, and of course, I will do this if they are willing to pay me for the labor.

Sometimes there are bigger directions you need to take as an artist, and they may cost you some popularity. The benefit is that the harder path will make your art more unique and authentic in the long run. My recent paintings have taken a turn away from that which is easily digestible for the art market, but for me, they are better paintings because of it.

Tell us about important teachers/mentors/collaborators in your life. There are many people who have made a pivotal difference in my life, but two people come to mind in particular.

I did not graduate from high school and had to go to summer school to get my degree. This made it very difficult for me to get into a college; I was even rejected by the state college when I first applied. The only person in my life at that time who believed in me, in my art, and my potential, was my high school art teacher, Deborah Alter. She advocated for me with the local state college, SUNY Purchase, and even arranged for me to meet and speak with the dean of the art department. It worked out because I got into the college after that meeting, graduated with honors, and was accepted into the Art Institute of Chicago right after, and even received a scholarship. If it wasn't for Deborah, I don't know where I would be. I would probably have still made art, but I don't think anyone else at that time expected me to amount to anything, let alone get into college.

The other person who changed everything for me was my wife, Tara. When she met me, I was broke, struggling to finish a MA in art history, living in a small room that was also my art studio, sleeping in a closet, literally, tutoring students full-time time and making very little money. This was ten years ago, and I was making art that is very related to what I still do now, but no one took the work I was producing at that time very seriously. Tara was the first person I had met in a very long time who actually believed in me and somehow didn't see me as a complete loser. If it wasn't for her love and support, I don't even know if I would still be here.

Sustainability in the art world is an important issue. Can you share a memory or reflection about the beauty and wonder of the natural world? Does being in nature inspire your art or your process? The human world, our art and culture, is not something that is separate from nature; it is an extension of nature. Since the earliest days, humans have created tools, paintings, and sculptures, objects that were direct extensions of our creativity acting upon the natural world. Art is always in balance with nature; art is one with nature. It is our over-dependence on fast and cheap solutions, usually marketed to us by those at the top of the economic and political pyramid, that makes wasteful new technology and production proliferate.

As an artist, I have always preferred to use the simplest tools, painting and drawing, and I have only done work with my hands. I use no special technology, digital rendering, projections, airbrushes, or anything. It is my personal opinion that if your art requires anything more than your eye, your hand, and the most basic mark-making tools, then it really isn't worth creating. This is just a practice I abide by; I don't seek to impose this on anyone, and certainly, there are many artists who have become much more successful than me using digital technology and having robots airbrush their canvases, and other such things that I would never do.

I live close to nature now, in the small Hudson Valley town where my family and I currently reside, so I see it in all its forms. Nature is filled with wonder, but it is also brutal and indifferent to suffering. It is the essence of the sublime: a wonder that staggers the mind, seduces the senses, but it is also nothing to be trifled with. Without our tools to protect us, the natural world could swallow us whole.

AI is changing everything - the way we see the world, creativity, art, our ideas of beauty and the way we communicate with each other and our imaginations. What are your reflections about AI and technology? What is the importance of human art and handmade creative works over industrialized creative practices? As best as I can tell, many of the same concerns about AI that are being raised now by artists echo the concerns that were had about photography in its earliest days. Famously, the French academic painter, Paul Delaroche, upon seeing a daguerreotype for the first time, said, "From today, painting is dead," and thus began the centuries-old tradition of declaring painting to be dead every few years.

The difference is that AI penetrates into every aspect of society, not just the arts or visual culture. I do not see it usurping the position of painting but rather becoming a new form of art making in the century to come, just as photography did. In order to do that, however, AI will have to become something more nuanced and impressive than it is, and the technology will also have to become less wasteful of energy. The cost of AI, both environmentally and economically, is not worth the word salad essays and creepy, lame animations that currently seem to be the limits of its capability.

What is strange to me is that the biggest market for AI continues to be in the creative fields, such as painting, writing, and cinema, even though it has been clearly demonstrated to anyone with intelligence and taste that the work produced by AI in these fields is subpar. I am puzzled as to why we need AI to do creative work for us. Who really wants that? There are so many artists, poets, musicians, and filmmakers with incredible talent. Are rich people just tired of there being an upwardly mobile class of creative people capable of influencing culture? At my more cynical moments, this seems to be the only advantage anyone could gain from promoting the replacement of skill, craftsmanship, and intelligence with AI slop.

Exploring ideas, art and the creative process connects me to The Holy Daimon. The Daimon is the greater consciousness I commune with in meditation and while making my paintings. I don't know what it is, and I no longer try to pin it down with definitions or proper names. It is a mystery to me, this voice that I hear, bringing the visions close to me. I prefer to just let it be a mystery. Some may call it a spirit guide, an angel, an alien, or any number of things. I am just here to receive its messages. The lightbulb doesn't have to understand where the electricity comes from; that's how I feel about this force.