Robert Zeller is an artist, writer, and curator who has exhibited at 511, Booth, Forbes, Palo, and Robilant +Voena galleries. He has been awarded two Posey Fellowships and a Pollock-Krasner Foundation grant. He has written essays for Sothebys, Brooklyn Rail, Whitehot, NGV Melbourne. He is the author of two books for Monacelli Press/ Phaidon: The Figurative Artist's Handbook (2017) and New Surrealism: The Uncanny in Contemporary Painting (2023). He has been interviewed by The New York Times, CNN, Whitehot, and other publications, and has given lectures at Rizzoli, Lyles & King, and Gagosian Beverly Hills and other venues. @robzellerart

How did the cultural landscape of New Orleans shape your creative vision? Originally from New Orleans, I am heavily influenced by Southern Gothic literature and the many mythologies surrounding the American Civil War of 1861-64, both of the North and the South. With its French and Spanish colonial heritage, New Orleans was once very European in spirit. I caught some of that spirit growing up there, though there is not much left. The city’s heritage is that of Creoles, of a Plantation slave-based economy that later became petroleum-based, of Southern aristocracy that fell on hard times after the Civil War, of pirates and voodoo, the economics of the Mississippi River (both of my grandfathers were longshoremen who worked the docks), of the birth of jazz and many other important aspects that form a complicated legacy. A proper assessment of the importance of New Orleans in the history of major cultural centers of the United States is often neglected. I believe that this is at least partly due to its participation in the Confederacy and thus being the losing side of the Civil War. Much of my art is about memory and loss, about unrequited love from a personal and a societal perspective, and New Orleans is a major factor.

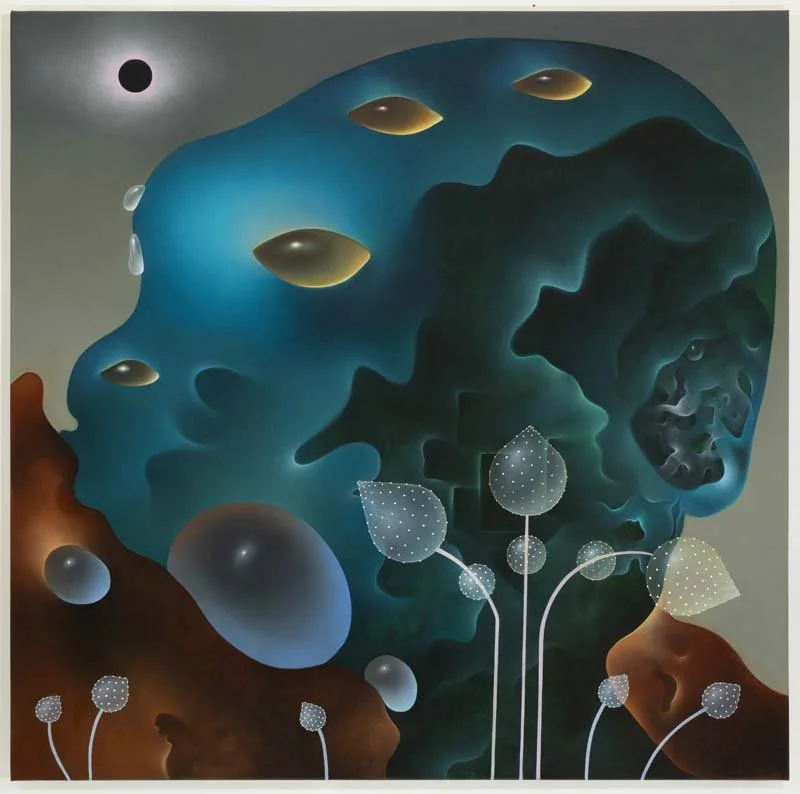

When did you first fall in love with art and realize you wanted to be an artist? For you, what is the importance of the arts? I was awoken to the power of art by attending mass at St. Louis Cathedral in New Orleans as a boy. My hometown is a very Catholic city. While St. Lois Cathedral is a young cathedral by European standards, it is very old for the United States. It is filled with Baroque-era Catholic art, and it had a huge influence on my tastes in art. The first time I saw landscape paintings was in a restaurant in New Orleans when I was a boy. They were copies of German Romantic landscapes of the type by Casper David Friedrich. I was absolutely fascinated by them. I knew I wanted to be a landscape artist, just by looking at the way those paintings captured the essence of Nature. Later, at the New Orleans Museum of Art, there was a Surrealist show that caught my attention. It's their irrational dreamscapes, psychic landscapes that caught my imagination—those of Salvador Dali, Max Ernst, Yves Tanguy, and Giorgio De Chirico.

What does your typical day in the studio look like? Walk us through your studio and your most used materials and tools. As I perform three different roles— artist, writer, and curator— I split my work week up into specific days devoted to each of those three tasks. The ratio of days devoted to each depends on the demands of the role at present.

1. As an artist, I usually have 2-3 paintings going. Some are in the sketch and design stage, others are ready to be painted, or are in the process of being so. I devote part of the day to each of these tasks. I like to listen to music or audiobooks while I am working, specifically on world history.

2. As a writer, I usually have an essay or two going, as well as a new book I am working on. On those days, I need total silence to focus. I am either reading source material or blocking in masses of text, or refining things with an additional pass of edits. As I write about contemporary art, communication with artists and galleries is a big part of my job as a writer. As I write about historical art movements, research is a huge part of my practice as well.

3. As curator, I am mostly constructing an overarching theme and writing an accompanying essay(s), as well as communicating with artists and the gallery hosting, as well as the galleries lending work. It's complicated, particularly group shows.

What projects are you at work on at the moment? And what themes or ideas are currently driving your work? I have a solo exhibit on display at Robilant + Voena NYC through Oct 16, 23, with drawings and paintings. An exhibit of work that I curated from my book "New Surrealism: The Uncanny in Contemporary Painting" is on display at Robilant + Voena Milan through Oct 17. That show —"A Mysterious Vision"— features 17 contemporary artists who are influenced by Surrealism, as well as a fantastic historical work by Leonor Fini.

Additionally, I just finished an essay for Sotheby's Insight Report that will be published in the next week or so: "Transform the World, Change Life: The Audacious Goals of Surrealism." Finally, I am writing a new book, "Witty and Macabre: the Flemish Influence in Contemporary Art," a book that explores the ongoing influences of Symbolism, Flemish Expressionism, and Surrealism in contemporary art in Belgium and the Flemish diaspora. That book will culminate in an accompanying exhibition at Palo gallery in NYC in Spring 2027 when it is published.

What do you hope people feel when they experience your art? What are you trying to express? The importance of the history of art, made relevant through our ongoing, ever-mutating human experience. We are art and art is us. Our perceptions of what is important and what is relevant change based on where we are and who we are. But these things we create never die. They are the finite expressions of infinite beings.

Which artists, past or present, would you like to meet? And why? Apelles, because he invented tetrachrome painting, painted Alexander the Great. Unfortunately, not one of his works survives to this day. Parmigianino, one of my favorite painters, I would beg him to teach me to draw in that old, incredibly mysterious Italian design manner. F Scott Fitzgerald, Graham Greene, and Ernest Hemingway, all formidable writers. All geniuses, all burdened with an understanding of the human condition, an understanding that surpasses my own. I could learn something from them, I'm certain.

Do you draw inspiration from music, art, or other disciplines? As I have stated earlier, I have a multidisciplinary practice, so I am always immersed in other art forms, in other disciplines that influence what I am working on at a given moment.

A great thing about living in New York is… There is nothing like New York. It is the greatest city in the world, to my way of thinking. The flow of creative energy here is incomparable to anywhere else. One is equally charged by it as one is drained by it. New York has America's Louvre in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, as well as other major museums (MOMA, the Frick, the Whitney, etc), thousands of art galleries, artists, writers, musicians, performers, as well as educators galore.

Can you describe a project that challenged you creatively or emotionally—and how you worked through it? My second book, "New Surrealism: The Uncanny in Contemporary Painting," took three years to complete and was life-changing. I had to reinvent myself to write it—completely change my outlook on life, on art, on my way of working. Everything I am doing now stems from that project. It was an enormous gamble that paid off in a major way.

I already had success from my first book, "The Figurative Artists Handbook." I was invited to teach workshops in Rome and Ireland. I was supposed to write a follow-up to that— a book on contemporary portraiture. Had I done so, I would likely now be known as a "figurative" writer and artist. Instead, I went in a totally different direction, towards contemporary Surrealism, one that has made all the difference to my life and career.

Tell us about important teachers/mentors/collaborators in your life. Conger Metcalf, an artist who lived in a small studio in the Beacon Hill neighborhood of Boston, had an enormous influence on me. When I was a student at the Boston Museum School. He took me on as a private student and taught me many, many important concepts as an artist that I still use today. While some are technical and formal, others are non-verbal and spiritual, as related to Venetian mysticism.

Another teacher at the Boston Museum School who was formative was an artist named Henry Schwartz, who taught me a lot about Dada and Surrealism. He tried his best to turn me on to Oskar Kokoschka, one of his teachers, but it never worked for me.

At the New York Academy of Art, Vincent Desiderio and Eric Fischl were very helpful in helping me form and realize my artistic worldview.

Some people come into their own quickly. Others are late bloomers, like me!!

Sustainability in the art world is an important issue. Can you share a memory or reflection about the beauty and wonder of the natural world? Does being in nature inspire your art or your process? Yes, spoke on this earlier, in regards to the first time I saw landscape paintings was in a restaurant in New Orleans when I was a boy. For my part, I go camping once or twice a year to reconnect to Nature, as the energy of New York is so urban. Upsate New York is stunningly beautiful and a reminder of what the Hudson River Artists of the 19th century saw in those vistas. “I go to the woods to be soothed and healed, and to have my senses put in order," wrote Henry David Thoreau. To go into the woods, leaving electric conveniences, cell phones, behind, is to walk into the presence of the basic elements—water, air, land, fire— and to find a presence larger than man.

AI is changing everything - the way we see the world, creativity, art, our ideas of beauty and the way we communicate with each other and our imaginations. What are your reflections about AI and technology? What is the importance of human art and handmade creative works over industrialized creative practices? AI —while an incredibly useful tool for corporations and their extensions—cannot replicate the greatest art of the human race because it has no soul. It has no metaphysical component. It is merely great at appropriation and synthesizing from that. But it is not creative in the spiritual sense, not in the least. In that, it fails.

Exploring ideas, art and the creative process connects me to… The infinite, the great I AM. Who always was and always will be.

The degree to which I, a finite being, can connect to that through my art is both an honor and a privilege.