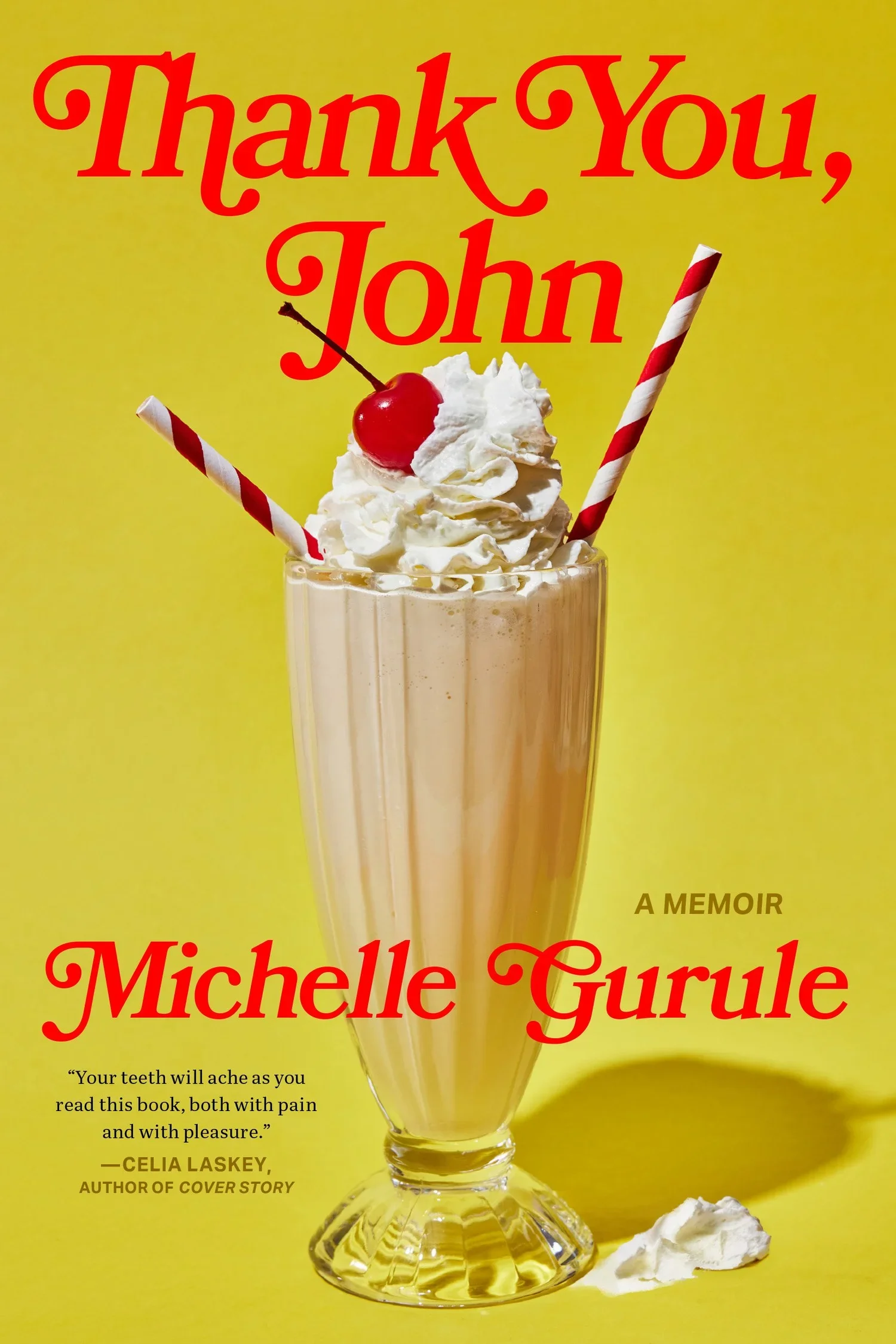

Michelle Gurule (she/her) is a writer and educator based in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Her creative work explores the complexities of sex work, class, power and Michelle’s intersectional identity as a queer, white/Chicana woman. Her memoir, Thank You, John, forthcoming Fall 2025 with Unnamed Press, is a comedy-tragedy, which follows 24-year-old, Michelle, a wanna-be writer, exasperated by poverty, bad teeth, and the poor choices of her family, through a tumultuous sugar daddy arrangement that she believes her destiny. Her work has appeared in Huffpost Personals, Electric Lit, The Offing, Joyland, StoryQuarterly, Homology, and others. @Michelle__gurule

You moved around in the U.S. as a child. What was that like for you, and how did your childhood environments shape your creative identity? I was born in Georgia, moved to Virginia as an infant, and spent eight years there with my mom’s family before eventually relocating to Colorado to be closer to my dad’s family. Virginia and Colorado are completely different worlds—geographically, historically, and culturally—and my mom’s and dad’s families are just as different. Both my parents grew up in large, poor families, but my mom is white and was raised in urban areas of the South, while my dad is Chicano and grew up in rural San Luis.

Being part of both cultures deeply shaped how I saw the world and understood my place in it. My mom is white, but our family is quite diverse. I have many white cousins and many mixed Black and white cousins. I witnessed racism both systemically and within our family. One core memory I have is being five or six and watching my white grandfather tell my Black cousins they weren’t allowed in his house, even though I was always welcomed. My dad also told me that my grandfather treated him as lesser for being Chicano and expected more labor from him. These moments were traumatic for my cousins and my father, and they were formative for me. I understood, even as a kid, that the world was deeply unfair, and I saw the ways racism—both structural and personal—affected marginalized people.

Growing up working-class, from a long lineage of impoverished people, I also think constantly about class. Identity and class are the core themes in all my work, regardless of topic—whether I’m writing about sex work, college, prison systems, or going to the dentist, those through lines are always present.

What kind of reader were you as a child? What books made you fall in love with reading as a child? I had so much fun reading as a kid. When I was really young, I was obsessed with The Magic Treehouse series, which made me curious about other cultures and sparked a desire to travel. I loved climbing into a story and entering a completely different world—exactly what stories are meant to do. I also loved Goosebumps and Animorphs and had so much fun talking about them with friends at school or seeing their adaptations on TV.

I became interested in nonfiction in high school when a friend recommended Tuesdays with Morrie by Mitch Albom and Me Talk Pretty One Day by David Sedaris. I thought it was so cool to read about real people, and I was instantly drawn to the genre. I spent all of high school reading whatever memoirs I could find and began dreaming of writing one myself. I journaled religiously and often shaped my own experiences into little stories. That journaling habit was a huge gift to my writing—it trained me to capture dialogue. If my mom said something funny, I’d jot it down. That impulse to document became second nature, and it definitely helped when I was writing my memoir, Thank You, John, which tells the story of my years as a sugar baby trying to claw my way out of student loan debt and poverty.

Do you have a structured writing routine, or does it shift depending on the day? I’m fortunate to have a flexible schedule as a remote lecturer—a job I worked really hard to land so I could devote more time to writing. A typical writing day starts at home or at a local coffee shop in Albuquerque, usually the latter. I’ll write for a few hours at a time.

Much of the last year was spent editing my memoir, Thank You, John, with my amazing editor, Allison Woodnutt. I’ve been working on that book since 2018, so by now it feels like second nature to sit down and sink into it.

Lately, I’ve been working on new essays, which have a different rhythm. I need to think through ideas, map them out, and work from outlines, though those outlines often shift as the writing reveals something new. I’ll usually start a session by reading a few pages from a book I’m currently into or revisiting a favorite essay, something that inspires me and reminds me how cool writing can be.

Tell us about the creative process behind your debut memoir, Thank You, John. Thank You, John is coming out this fall. It’s a come-tragedy that chronicles my time as a sugar baby in my mid-twenties and explores class and identity in America. It’s also a book about family and the secrets we keep.

This book was a personal reckoning for me. It documents a period of secrecy and survival. I never planned to tell anyone I was in a sugaring arrangement, but once it ended, all I could do was write about it. The story needed to be exorcised. Writing it helped me understand that part of my life, and I hope reading it offers that same kind of insight and connection to others.

Do you keep a written record of your ideas, observations, or writing sketches? I’ve kept journals since I was ten. I still have crates of them, and I love flipping through them from time to time. It’s so strange and wonderful to revisit the thoughts of my thirteen- or seventeen-year-old self.

As a teen, I wanted to be a poet or songwriter, so those early journals are full of poems and lyrics. They’re hilarious now but so heartfelt. These days, I journal to process emotions or document my days. Sometimes I respond to prompts or brainstorm essay ideas. Journaling has always been a companion to my writing life.

You’ve mentioned that research is essential to your writing. How do you go about the research process? It can take many forms. Sometimes it’s traditional—visiting archives or reading source texts to support my ideas. Sometimes it’s more casual, looking up details to confirm memories, like what year the Spice Girls went on tour. And sometimes it’s more journalistic. I’ve conducted interviews, though I wouldn’t say it’s my strongest skill.

Even in memoir, accuracy matters. Research helps me anchor my memories in fact, and occasionally it opens new lines of inquiry that deepen the personal story I’m telling.

Which writer, living or dead, would you most like to have dinner with? This is such a hard question! There are so many. But I recently read The Dry Season and admire Melissa Febos’ work deeply. I relate to her past as a sex worker, and I’m inspired by how she’s evolved into writing about different topics over time. Sex work is a big part of my story, but it’s also starting to feel historical to me. I’m in a different season of life and I’m curious about how my writing will evolve. I’d love to talk to her about that process.

Do you draw inspiration from music, art, or other disciplines? Definitely. I’m a huge Tegan and Sara fan and was always fascinated to learn they sometimes wrote songs inspired by books. I don’t often write directly about other art, but it’s always present in my life, so it seeps into the writing.

Art shows up in my scenes—what I’m listening to, watching, or surrounded by—because those cultural references carry tone, class markers, and emotional resonance. They do a lot of heavy lifting in building a world on the page. I have my favorite shows I like to make references to as well, like The Simpsons.

How do you see technology—especially AI—shaping the future of writing and literature? What are your hopes and concerns? AI is artificial, and writing is all heart. I didn’t write my memoir because I had to, I wrote it because I needed to. It poured out of me. What makes the book special is that it’s me—my internal world laid bare. That kind of human storytelling can’t be replicated by a machine.

Publishing AI-generated work for profit at the expense of real writers would be an ethical failure. Readers and consumers need to make it clear that we value human storytelling. Publishing should protect and prioritize the people in every step of the creative process.

Tell us about some books you've recently enjoyed and your favorite books and writers of all time. I recently read Alligator Tears by Edgar Gomez and was obsessed from the first page. He writes about growing up as a queer, poor, Florida-born Latin American. It was hilarious, heartbreaking, and deeply relatable.

I also read The Holy Hour, a mixed media anthology about sex work and the divine, edited by Molly B. Simmons and Emily Marie Passos Duffy. It was so powerful and moving. I especially enjoyed Elena Egusquiza’s essay, “The Sacred Prostitute: Sex Work as a Tool for Resistance, Liberation and Healing,” which reframed some of my own experiences. She writes about witnessing “a raw, spontaneous honesty arising from a deeply embodied place” during an interaction with a client, and that line really struck me. I’ve experienced that kind of confessional moment with clients too, as a dancer and a sugarbaby, and I now look back on those exchanges with more tenderness and curiosity, like what does embodiment make emotionally available?

Exploring literature, the arts, and the creative process connects me to… My most authentic self. My spirit. My family, my friends, strangers. It connects me to people.