Remica Bingham-Risher, a native of Phoenix, Arizona, is a Cave Canem fellow and Affrilachian Poet. Her work has been published in The New York Times, The Writer’s Chronicle, Callaloo, and Essence. She is the author of Conversion (Lotus, 2006), What We Ask of Flesh (Etruscan, 2013), adapted into an immersive dance and installation work by INSPIRIT Dance Company, and Starlight & Error (Diode, 2017). She is an in-demand speaker at festivals, libraries, bookstores, colleges, and universities and has been a featured performer at the Kennedy Center, Dodge Poetry Festival, and numerous other venues. Her memoir, Soul Culture: Black Poets, Books and Questions That Grew Me Up, was published by Beacon Press (2022). Her newest book, Room Swept Home, poems and photographs from Wesleyan University Press (2024), was chosen as an Honor Poetry Book by the Black Caucus of the American Library Association (BCALA) and won the L.A. Times Book Prize. @remicawriter

Where were you born and raised? How did it influence your writing and your thinking about the world? I was born in Long Branch, New Jersey. I am an Army brat, so we moved around a lot, but I was raised primarily in Phoenix (really Glendale), Arizona, from the time I was in second grade to the last few years of high school. By the time I was about to finish high school, we moved to Norfolk, Virginia, to help take care of my maternal grandmother.

I think moving around a lot influenced my writing and the way I think about the world. Born in Jersey, moved to Germany, then to Georgia, then to Phoenix, all of that helped me feel transient, sometimes fearful, but sometimes unstuck, you know what I mean? I learned that I could make friends almost anywhere, and that was a joy for me. I also learned that it could feel so disorienting to be in a new place with unfamiliar people, but books and words on the page always gave me a strange kind of comfort. So the writing became a friend just like any of the other folks I met over time. It’s still that way.

What kind of reader were you as a child? What books made you fall in love with reading as a child? I was a voracious reader as a child. I loved books from very early on because my mom read to me when I was in the womb (bless her). Finding books about little Black girls, books by Black authors, was kind of the cherry on top of things for me. Growing up in Phoenix, where the black population was little to none, I often felt like it was impossible to find myself or images of myself anywhere in that space. But the library helped me find authors that I loved, like Eloise Greenfield, oh and especially Walter Dean Myers. I ran into his son, the illustrator Christopher Myers, a few weeks ago. I was just so excited to tell him how much his father really changed my life and my understanding of myself as a young person. Books did that for me. Reading people like Mildred D. Taylor and Virginia Hamilton made me understand that there was certainly a place for me in the world.

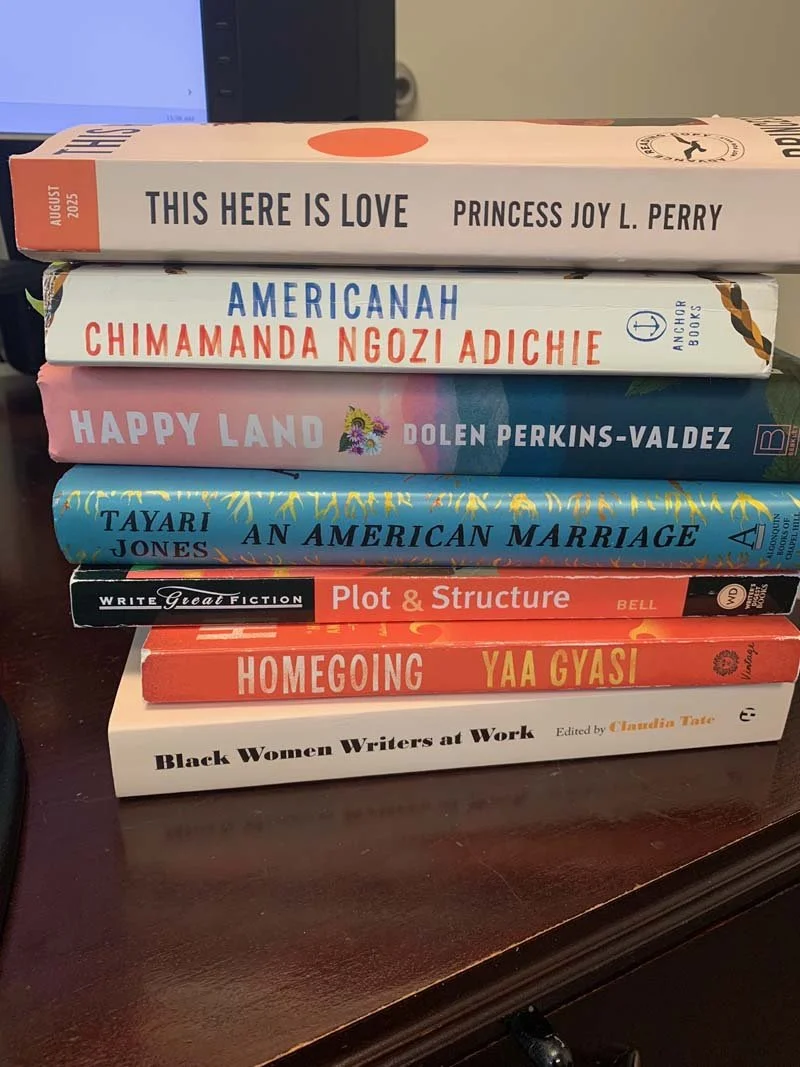

Describe your typical writing day. A typical writing day for me—if I have my druthers—usually starts around 7:00 AM with a ‘nonfat venti hot chocolate keep the whip’ from Starbucks, or a hot jasmine green tea with lemon and honey. I usually ease my way into writing by reading a little bit of whatever I’m in the middle of. I’m always reading three or four books at a time, particularly in different genres. I’m usually reading a book of fiction, a book of nonfiction, and a book of poems. Right now, I’m going back to a dear friend of mine, Princess Joy L. Perry, whose debut novel This Here is Love is coming out this year. It’s really helping me with novel revisions of my own that I’m working on. I certainly consider myself a poet in every sense of the word, so writing prose is proving difficult for me, but it’s an exciting challenge. It’s a Black love story, and I’ve always wanted to see more of those in the world. When I finished my memoir, Soul Culture: Black Poets, Books and Questions That Grew Me Up, a few years ago, I decided, okay, you’re proven to yourself that you can write a book of prose, so now it’s really time to jump into the deep end and here I stand.

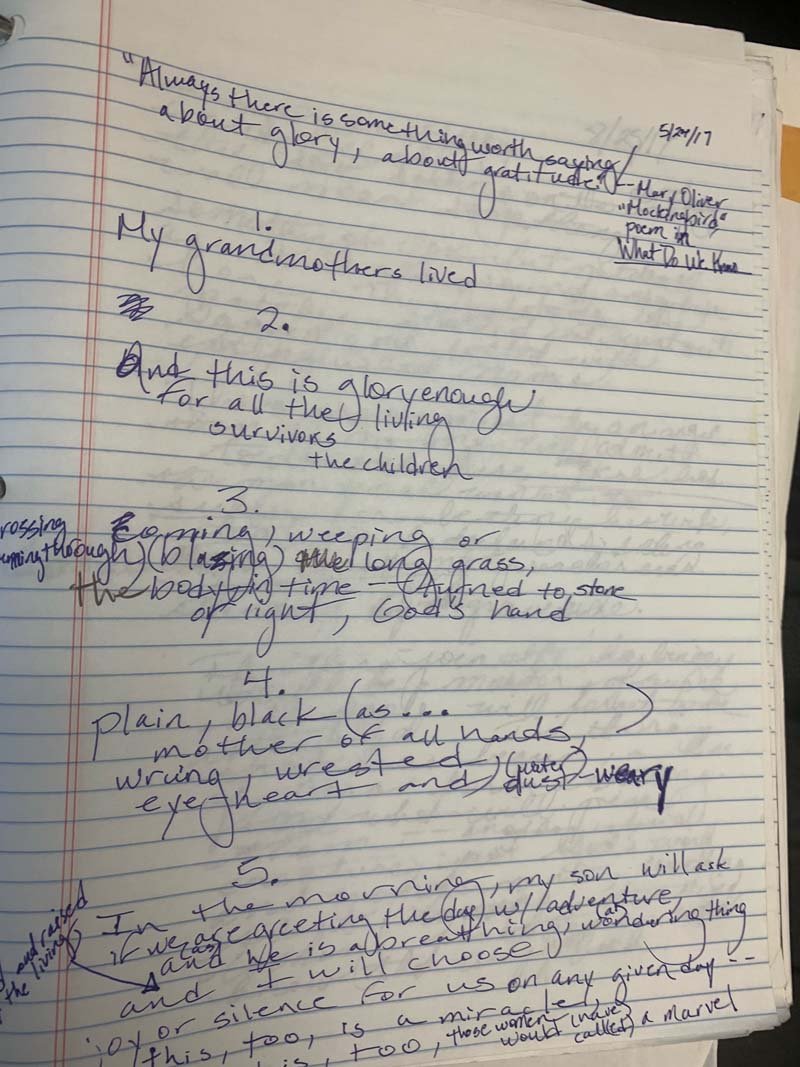

I’m definitely a pantser, not a plotter. I don’t generally outline any of my books before I work on them. Somewhere in the middle, though, an outline can often become imperative. Even for my last book of poems and photographs, Room Swept Home, eventually, because it was dealing with the lives of two of my grandmothers, I did have to outline the book to make sure I wasn’t leaving out important personal and historical details. With the novel right now, I absolutely wrote the first draft without an outline. Now, in the third or fourth round of strident revisions, I’m working piece by piece from a very loose outline. I love to discover what comes when I am forced to wrestle with a blank page; it’s part of the joy of writing for me. The bigger joy is the revision because that’s where you get to make it beautiful.

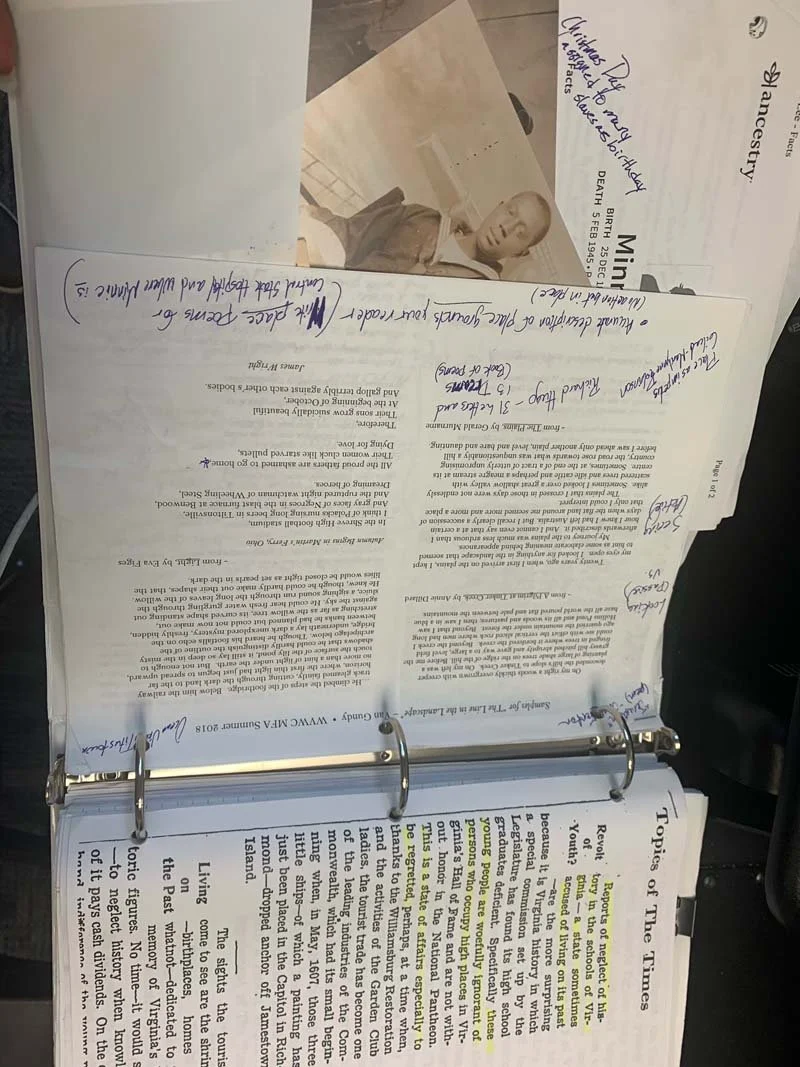

Tell us about the creative process behind your most well-known work or your current writing project. At this moment, I guess my most well-known work is Room Swept Home because it just won the L.A. Times Book Prize. It was also named an Honor Book by the Black Caucus of the American Library Association (BCALA), and has been a finalist for some other prizes and awards. I’m really grateful for all the attention it’s getting, as the book is about two of my grandmothers who intersected in Petersburg, Virginia. They were within one mile of each other in 1941 and certainly had no idea that that would be the case. One of my grandmothers, Minnie Fowlkes, was interviewed for the WPA slave narratives. Another grandmother, Mary Knight, was sent to the Central Lunatic Asylum for the Colored Insane after birthing her first child, as postpartum was an ongoing mystery then.

My process when writing that book was to do much ethnographic research, interviewing as many of the living grandmothers, aunties, distant cousins, and family members that I could who had ties to these women. I also spent countless hours in libraries and historical archives, piecing together the contextual lives and times of women who are often left out of the archive. Much of the work was writing persona poems in the voices of these women, writing formal verse to try to get some emotional distance from things that would leave me spent and broken, having to recount the hardest circumstances of their lives over and over. I was also determined to build in joy whenever we could because their stories are really a triumph. They both lived to 84. They both had seven living children in the world by the time they left here, and they certainly ushered in all the folks who ushered in me. So it was a long process—it took at least seven years to write, and it was worth all the blood, sweat, and tears. I’ll be glad to kind of move in a direction that’s as far away as it can be with the new project that I’m working on. It’s fiction, so I can move as far into the imaginary as I would like to, and that, too, is a gift.

Do you keep a journal or notebook? If so, what’s in it? No, I don’t keep a journal currently. The closest thing that I get to one would probably be the Notes app on my phone. There you’ll find everything from an endless list of things I need to pick up from the store, poem fragments and lines, research ideas, and quotes from writers that I love.

You’ve mentioned that your work with the archives was integral to your work on Room Swept Home. Does historical research always speak through your poetry? How do you go about conducting your research? Oh, I love research. I’m one of the few poets you’re fine who insisted on having a selected bibliography in the back of a poetry book! It was in Room Swept Home. But the Notes section of each of my books is chock full of research and ephemera. I also read the Notes sections first in any book I pick up because I want to know how folks got to a place before they got there and why.

I love spending time in archives, putting on the white gloves, and sifting through archival documents. It makes me feel like I’m becoming a part of history and also helps me understand where we are in the present. Research helps me flesh out the feelings that I have about how we got here and add context to old haints.

Which writer, living or dead, would you most like to have dinner with? James Baldwin. My goodness, can you imagine sharing a table and an evening with him? Also, of course, Toni Morrison comes in a close second, especially if she’s cooking the dinner. I’ve heard that woman could burn in the kitchen, and she certainly wears us out on the page.

Do you draw inspiration from music, art, or other disciplines? Oh yes, I love being inspired by other art forms. In my third book, Starlight & Error, many of the poem titles are song titles. Music plays a big part in my family, surely when I was growing up with my parents, and especially now in my house that is full to bursting with my husband and kids, and grandbaby. I don’t generally listen to music when writing a first draft, but I play music throughout parts of the process. When I am in the final stretch of a serious revision, I always listen to Beyoncé.

I also love ekphrastic work, so I enjoy looking at visual art—photographs, sculptures, paintings—and finding the poem in those as well.

AI and technology are changing the ways we write and receive poetry. What are your reflections on AI, technology and the future of storytelling? And why is it important that humans remain at the center of the creative process? I teach faculty at my university about critical reading, critical thinking, and disciplinary writing skills, and as you can imagin,e much of our conversations lately have circled around AI.

I think the fear that we had that AI would destroy everything we knew about original thought is steadily being laid to rest. The same way the calculator didn’t ruin everything for mathematicians, AI won't ruin everything for the writers or scholars. What people need to understand is: AI is all brain and no heart. It can’t recreate with any certainty authentic experience, context, or piece together living in the way that the human brain and heart can. So, for a while, my job is safe because AI is still pretty terrible at writing poems! (But my work and the work of many others is being fed to it, so it will get better.)

Even though it’s being built on the backs of those who are human thinkers, it’s also being built with the bias implicit in human thinkers, so now our job as those who believe deeply in ethics, empathy, original ideas, beauty, and lyricism is to continue to find ways to move new work into the world that wrestles with all the things that AI can’t. We also have to help students understand that writing is a learning tool, so burrowing through their own ideas and the ideas of others will help them learn how to function. In short, we’ve got to rely on having real-life experiences, giving thinkers agency, trying to make sense of all the fraught, joyful, wondrous living we do in the world, and we have to craft it with heart.

Tell us about some books you've recently enjoyed and your favorite books and writers of all time. I recently fell in love with Geraldine Brooks, especially her book Horse. I’m now trying to read my way through much of her historical fiction. Other than the writers I have already mentioned, like Baldwin and Morrison, I adore Lucille, Clifton, Sharon Olds, Elizabeth Alexander. August Wilson will be the playwright of my heart always, but I am deeply enamored with theater, so I go back to Suzan-Lori Parks and Lynn Nottage quite a bit. I’m just chomping at the bit to at least read Purpose by Branden Jacobs-Jenkins when I get a chance to.

Exploring literature, the arts, and the creative process connects me to… Myself and God. I turn to poetry in the same way that I turn to prayer.