Sally Bayley is the author of a series of ground-breaking books which defy category and genre. All explore the relationship between biography, autobiography, and fiction through myth, fable, fairytale, and forms of lyrical and visual memory. Published works include her three-part coming-of-age sequence, Girl with Dove, No Boys Play Here, and The Green Lady, as well as a study of the diary as an art form, The Private Life of the Diary. Sally hosts and performs the highly successful podcast A Reading Life, A Writing Life, designed to inspire creative writing, innovative reading, and artistic responses to living. She is a member of the Royal Literary Society and her next book, Pond Life, is due for publication this year. @bayleysally

How did your upbringing on the south coast of England shape the way you think and write about the world? I grew up in a poor working-class provincial seaside town that used to be a watering hole for the middle classes. Little Hampton, West Sussex, about twenty miles west of Brighton, a much more fashionable resort, and just over an hour, maybe an hour and a half, from London by train. But, unfortunately went into decline from the 1980s, when cheap holidays, package holidays abroad, became fashionable, and that sense of small seaside towns, stuck in the past, is fundamental to my sense of history and place that exists outside of time, a left behind place – a place in arrears to modernity. It allowed me to create a place that is a-historic, outside of time – a place of myth. It is easy to start writing from the past in such a place because it is already in the past.

One of the key factors of where I came from is that it is a terminus: a railway terminus. I think that the idea of a terminus is very important, the end of the line. So, it’s a place easy to write about in relation to elsewhere because, as a child growing up there, you were always dreaming of leaving and going elsewhere. The railway line and trains are very important to my writing as well. We used to speak of catching a train up to London: “up,” a geography of escape but also of ascendancy. If you got to London, you were ascending the social scale – back to the story of Dick Whittington, who sought his fortune in London. Or Charles Dickens’s David Copperfield.

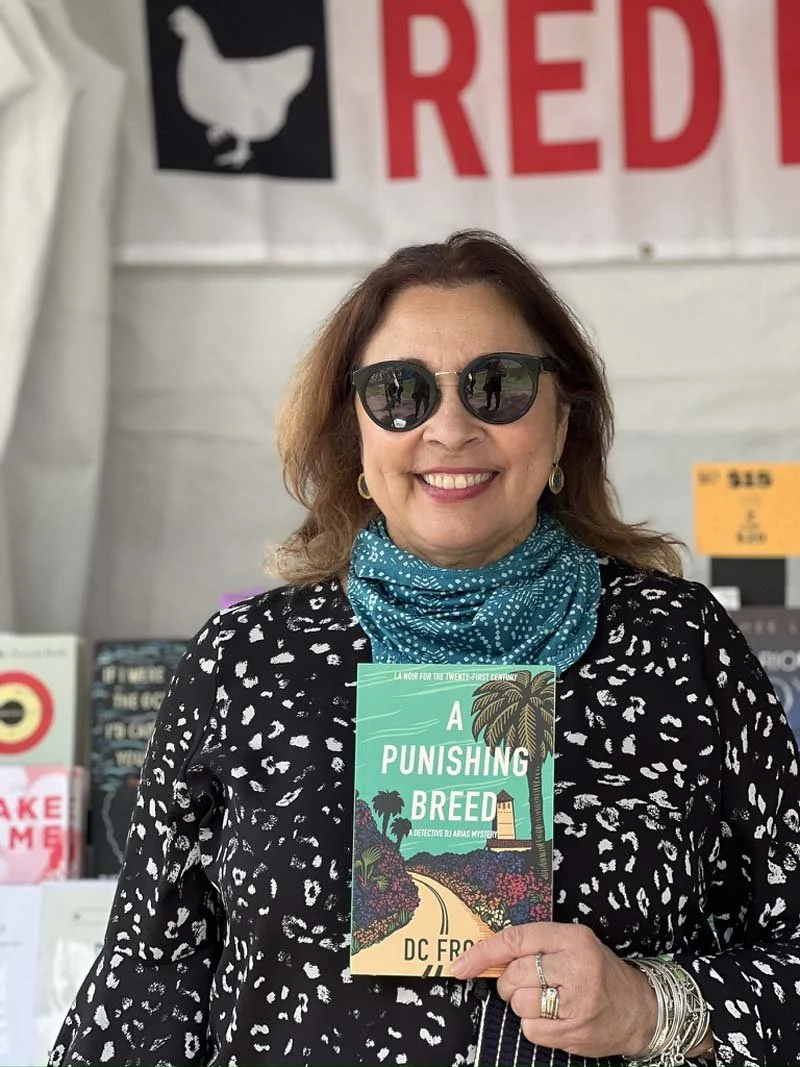

What were the books that truly captivated you as a child? Were there any that made you realize you wanted to be a writer? Murder mysteries, the mystery genre, the genre of detective fiction, which I am now teaching to Americans visiting Oxford. Anything involving clues and a figure of authority, like the detective figure. I read all of Agatha Christie. I was in search of a form of narrative authority I realized from a very early age: who gets to tell the story, who gets to announce everything, a person who resides over a community of people. Then I went straight from Agatha Christie to Charles Dickens. Charles Dickens, Bleak House, there’s a Mr. Bucket, the detective. I was looking for a sense of other people’s houses, other people’s homes, other people’s domestic lives, and detective fiction always takes place, usually around the domestic realm. Agatha Christie. Particularly the Miss Marple stories, in which Miss Marple stood in for a version of my grandmother: an older woman with authority but with a strong sense of benevolence and care like a fairy godmother, and it was my grandmother who taught me to read. I related to the Miss Marple character because of her fostering of young girls; she fosters maids from the orphanage, and the idea of being fostered by a benevolent figure was important in my teenage years. I was interested in fiction like the gothic and detective genres, which mix rationalism with magic, and the fairytale/fable form.

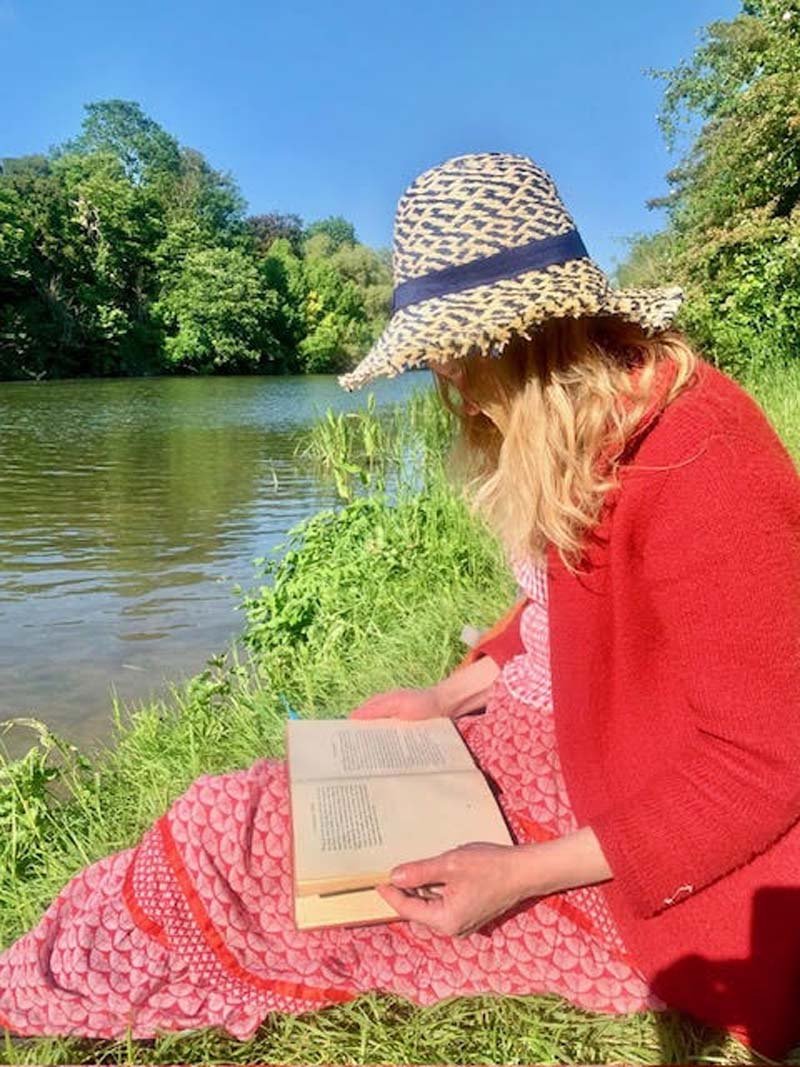

Describe your typical writing day. I read first because that settles my relationship to words. I always try to read even if it's just for ten or fifteen minutes; it settles my brain and relationship to words. Because sentences, I love the order of a sentence – syntax and grammar, rhythm.

And then I often go for a swim, and that sense of the flow of the river provides me with a sense of propulsion and a wider context: nature. River, willow trees, birds overhead; I look up at the sky, the world around me, and I begin to see the universe, to see things in a larger way, more panoramically. Then I come back inside and do more writing. I am trying to build a rhythm.

Another rhythm I live by is the sound of my tea kettle. I usually have three cups of tea before I talk to anybody.

I usually schedule my teaching for between eleven to one because I am most able to feel articulate then, so that my teaching comes out of my writing.

I might have a phone call when I mentor somebody, abroad, in America or Canada, on their manuscript, giving them reading sources and close-reading.

I usually spend some time playing, because playing is very important to my writing. So I often play after school with the children in the community.

I live on a narrow boat, on a small tributary stream on a branch from the main Thames. I read in the evening. Sometimes I need to listen to the human voice. I love interviews, if they are good, because they help me structure the sound of thinking, not blabbering on, so that’s why a good interview can be very helpful: it’s a kind of dialogue, so I need to hear the sound of dialogue.

And the children’s voices, when I play with them. They are natural philosophers; they ask questions about being – why we are here, what we are for. They are existentialists and they are natural eccentrics before we take it out of them; they are my kin, so I have to be with them at some point in the day. I also like being asked what I am doing. They always ask direct questions of purpose, which are very helpful to me.

Tell us about the creative process behind your most well-known work or your current writing project. I am interested in lost lives, what Virginia Woolf called lives of the obscure, which is a mixture of short stories and miniature biographies—for example, the life of Ms. Eleanor Ormerod. I am interested in the small people of the world, the people who aren’t seen: the opposite end of the celebrity spectrum (hint! hint!). I often see the world from a child’s point of view, as in my first book, Girl With Dove, which is told through the child's voice but is an adult work of fiction—I would say experimental adult biography. I spend quite a lot of time looking at the minute, and this is true, and this is something that I learned from reading and teaching Victorian literature, but also understanding the Victorian interest in entomology, which is insects, right? So I often just spend time looking at small things that stick to my window. My windows are very important to me. I watch the small things moving around my boat that are living, which is to say insects. Which is what my book coming out next year, Pond Life (The New Menard Press), is about: things beyond the surface. Spiders caught in webs on my boat, cobwebs, feathers, lady-birds: we’ve had an influx of ladybirds this year, they are everywhere, in our hair. We have also had a huge influx of ermine moths, whereas before they were moths or caterpillars. They spin webs all over our boardwalks, trees, tents, all over all of our belongings in the meadow where I’m moored. This is what I did to start generating my book Pond Life, which is about small lives in a small provincial town, loosely based on the town I grew up in: people who scuttle around like insects, beetles that we don’t notice.

A lot of it is also inspired by being a child—when you spend a lot of time grubbing on the ground and you are fascinated by small things, the things you can hold in your hand, like lady-birds, caterpillars, and on the seaside we were captured by sandworms and all sorts of things. Natural history.

Do you use a journal or notebook? If so, what do you keep in it? I keep a commonplace book of words and phrases that I find interesting. I’ve written about the diary as an art form, so I’ve always been interested in diaries as spaces for dress-rehearsing your voice, as in the tradition of Sylvia Plath and Virginia Woolf and Katherine Mansfield.

How important is background research in the kind of writing you do? I usually organize my books around one central figure who acts as a kind of organizing principle or significant form, and at the moment, in the current book I’ve started, which follows from Pond Life, I am organising my characters around Mrs. Parnell, who was the lover and wife, for a brief year or two, with Charles Stewart Parnell. Parnell was the home rule leader, the leader of the Irish Independence movement, the movement for home rule in Ireland. My book is being organized around their relationship because I don’t want to write a straightforward biography. I am really writing about her early marital period, her disappointment. I’m interested in disappointment. Her first marriage was a great disappointment to her: she married a feckless, steeple-chasing man who spent all his money gambling but wanted to be a member of the British parliament. And then I jump over quite a bit of history, like a race horse, several historical hedges, until we get to the end of her life after Charles Stewart Parnell died and left her. He died in 1945 and they had only been married for about a year, and before that they were just living as lovers. And I am interested in the part of her life that hasn’t been recorded thirty years after he died, because that is where the fiction lies. She was wandering for thirty years around the seaside towns, which I know well because I grew up there. She actually died in the town I grew up in. I want to speculate about the life she lived after her second husband died.

Which literary figure would you love to share a long, slow meal with? That’s a really hard question. I think I’d like to have met Jean Rhys, because Jean Rhys’ life reminds me a lot of the life that Mrs Parnell lead after her husband died, wandering from boarding house to boarding house, so right now that would be particularly interesting to me: living in these shabby rooms, lonely rooms, socially unmoored – she felt like an outside, Jean Rhys.

Do you draw inspiration from music, art, or other disciplines? Art and music are very important to my writing: art music poetry ballads hymns songs. I am always looking for rhythm and structure and a painting can offer you a visual structure, a way of ordering things. A composition is simply a way of ordering a narrative.

I often listen to songs because every writer is looking to capture images, but images can come through the visual imagination or auditory imagination or both working together, and I think songs produce both.

I often sing hymns outside to myself as I did as a child because they offer a rigorous structure like a ballad that you can fold your ideas, your story, into.

AI and technology are changing the ways we create stories. What are your reflections on AI, technology, and the future of storytelling? And why is it important that humans remain at the center of the creative process? Because, I think, as one human being to another human being, we want to be recognized for our peculiarities. Let's use an example from our detective fiction course. I am currently teaching detective fiction to visiting students, and we are reading the Conan Doyle stories, and our conversation today was all about the peculiarities of Sherlock Holmes. The reason we like Sherlock Holmes is that he is an eccentric: he has peculiar habits, a peculiar mindset, a peculiar way of reasoning, and a peculiar domestic arrangement. And those are the reasons why we like him. He is an original. He teaches us to notice foibles and all human beings crave to be recognized for their individual marks, habits, foibles, ticks, whatever you want to call them. I also don’t think AI can ever fully replace a unique literary voice, I just don’t believe that, such as JD Salinger for example: a unique syntax, you could say. The reason that singers with unique voices, like Amy Winehouse and Bob Dylan, endure is because of their unique tone, sound. I don’t believe you can generate by AI a Bob Dylan. The other thing about a unique voice is that you want to be around the body: you want to be around the body of the singer. For me, writing is very visceral, very close to performance. I have been told my writing is uniquely close to performance: in other words, embodied presence – and that is what voice is, embodied presence.

Who are some authors you’ve recently enjoyed or your favorite writers of all time? Tell us what draws you to them. Alice Thomas Ellis, who was born in Liverpool but moved to Wales via Chelsea in London, has a unique literary voice that is very warm and witty, and she combines a sense of the occult and magic and the supernatural and superstition with quite a steadfast set of references to religion, catholicism, and ritual. But it's her wit – the way that she slides between a sense of the domestic world as having a proper order or conduct and then something that might radically interrupt that order with the arrival of a radical particle, an outsider, a disruptive force – sometimes that force is an illegitimate emotion, such as an unsuitable form of love, as we see in The Other Side of The Fire where the housewife, Claudia Bohannon, falls in love with her husband’s son, i.e. her stepson; or with the arrival of a young black postulant fresh from the nunnery, as in 27th Kingdom.

Exploring literature, the arts, and the creative process connects me to… Somewhere beyond myself.